Can Hydrocarbons Catalyse New Out of the Box Thinking on Cyprus? A Turkish Cypriot Perspective

Can Hydrocarbons Catalyse New Out of the Box Thinking on Cyprus? A Turkish Cypriot Perspective

Mustafa Ergün Olgun*

Cyprus is co-owned by its two politically equal and inherently constitutive communities that have shared the island for over four centuries. Neither community may claim authority or jurisdiction over the other under the international treaties that granted Cyprus independence from the UK in 1960.

Sadly, the bi-communal government formed with independence collapsed after three years due to the seizure of the seat of government by the Greek Cypriot side, which has since claimed to represent the Republic of Cyprus (ROC) at the expense of the Turkish Cypriot side. A UN Peacekeeping Force was despatched to the island in 1964 to prevent a recurrence of fighting and to contribute to a return to normal conditions.

The UN is still in Cyprus, without much success. Since 1964, there are two governments on the island with a hostile, albeit thankfully no longer violent, relationship, as each side administers the territory under its control.

After decades of involvement in Cyprus negotiations aimed at establishing a new bi-communal partnership I am today convinced that a strong stimulator is required to break the entrenched stalemate, which the over 40 year-old UN facilitated negotiation process has failed to achieve.

The discovery of hydrocarbons in the seas surrounding South Cyprus has added a further international dimension to the Cyprus issue, putting new pressure on the status quo. The reserves can both reinforce or scuttle the ongoing political stalemate on the island, with the potentially negative ramifications impacting large multinational companies investing in the area as well.

The issue is complex, not least since the Greek Cypriot side and Greece are also engaged in a dispute with Turkey over the delineation of Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and continental shelf claims in the Eastern Mediterranean. All these issues inevitably also touch on the perennial Aegean dispute between Greece and Turkey, but are also further complicated by the intricacies of international relations in the Eastern Mediterranean, given that extensive hydrocarbon reserves have been discovered in Egyptian, Israeli, Palestinian and Lebanese waters as well.

In this respect, international actors, including the EU, the US and the United Nations should redouble their efforts to ensure that the discovery of hydrocarbons becomes an enabler – or “blessing element” – as opposed to a further hindrance – or “curse element” – to political efforts on Cyprus, or indeed the broader Eastern Mediterranean.

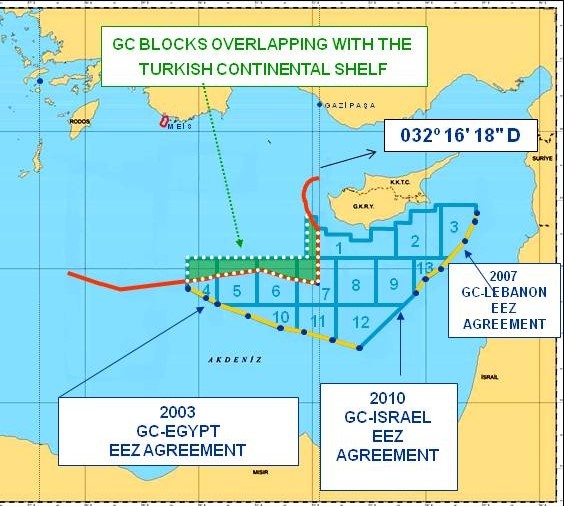

With regards to Cyprus, tensions began escalating as the Greek Cypriot side signed maritime border agreements with Egypt in 2003, with Lebanon in 2007 and with Israel in December 2010. Because there has been no official sharing of the joint natural resources of the island, the Turkish Cypriot side strongly objected to these unilateral agreements. It is worth recalling that Greek Cypriot authorities had refused both a two state solution (separation) in 1983 and the UN power-sharing plan of 2004 that aimed to unify the island before EU membership.

Then, in late January 2007, the Greek Cypriot side divided its claimed EEZ into 13 licencing blocks and went out for international tenders. Blocks 1, 4, 5, 6 and 7 partly overlapped with the Turkish Continental Shelf, adding yet another dimension to the dispute[1] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 | Map of Turkish continental shelf and overlapping Greek Cypriot gas blocks

Source: TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and Ergün Olgun, “Cyprus – Unilateralism on Hydrocarbons Will Result in Permanent Division”, in T-Vine, 15 January 2018, http://www.t-vine.com/?p=7905.

Despite Turkish Cypriot and Turkish objections, the first licence was granted to US company Noble Energy in October 2008 for parcel 12 (Aphrodite), which is across the border with Israel where Noble was already operating. Drilling began on 19 September 2011 and the field is now estimated to hold 4.2 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas.

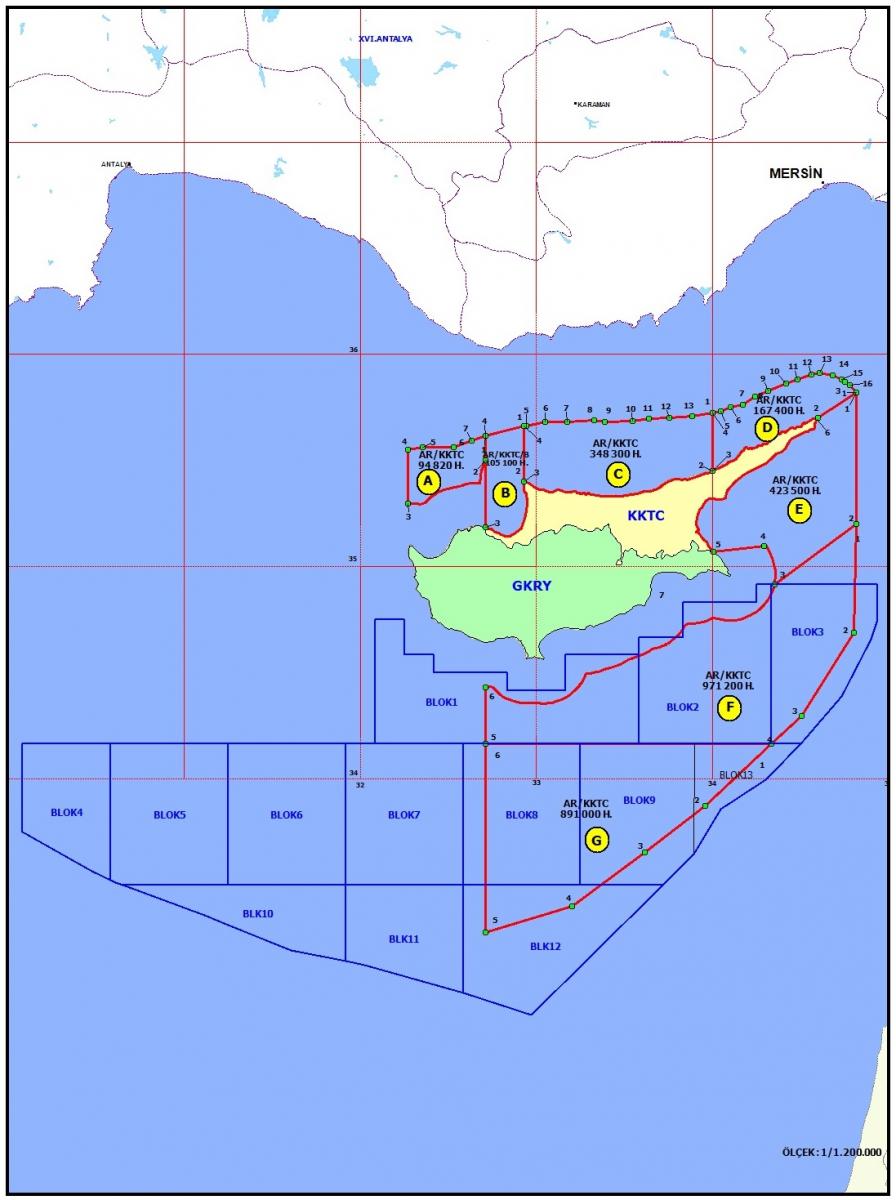

This action invited a response from the Turkish Cypriot side, which signed a Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement with Turkey on 21 September 2011. This was followed on 22 September 2011 by the signing of a licencing agreement with the Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) for all areas claimed by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) to the north, east and south of Cyprus (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Overlapping licencing agreements, TRNC (red) and ROC (blue)

Source: TRNC Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On 24 September 2011 Turkish Cypriot authorities made an offer to the Greek Cypriot side through the UN Secretary-General to either jointly suspend all hydrocarbon exploration activity until an urgently needed comprehensive settlement is reached, or to form a joint “ad hoc” committee, with participation from the UN, that would be responsible for the joint operation of all hydrocarbon activity.

The Greek Cypriot side refused both options on 4 October 2011. While the Turkish Cypriot offer is still on the table, Turkish research vessels Piri Reis and Barbaros have since conducted seismic studies in the blocks licenced to TPAO. Follow-up drilling is expected soon in potentially promising areas.

The Greek Cypriot argument that the ROC is sovereign and will not discuss its hydrocarbon initiatives with the Turkish Cypriot side violates the established principle of political equality and only helps perpetuate the conflict.[2] Equally, recent developments are undermining the peacekeeping and good offices missions of the UN, the central purpose of which is to provide an environment conducive to the resolution of the Cyprus issue.

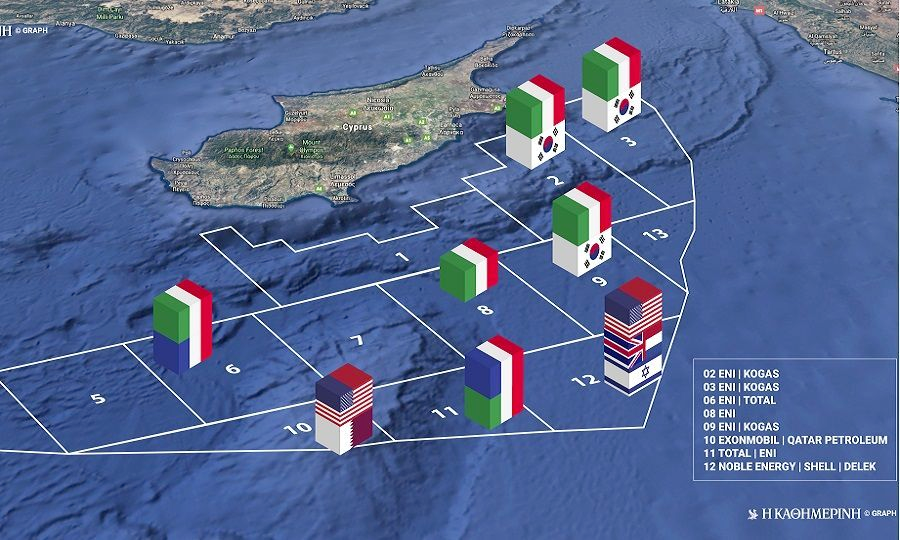

Today, large multinational companies such as Noble Energy, Eni/Kogas, Eni/Total, ExxonMobil/Qatar Petroleum and Shell are all actively engaged in the Greek Cypriot hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation process (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 | International tenders and offshore exploration in the Greek Cypriot EEZ

Source: Apostolis Tomaras, “Exxon - Total for Block 7”, in KNEWS, 4 October 2018, http://knews.kathimerini.com.cy/en/business/exxon-total-for-block-7.

In early 2018, the Italian company Eni carried out exploratory drilling in Block 6 (Calypso), which is believed to hold between 6 to 8 tcf of natural gas. Currently, ExxonMobil and Qatar Petroleum are jointly conducting exploratory drilling in Block 10, which is bordering Egyptian gas fields.

The refusal of cooperation, and the Greek Cypriot side’s unilateralism is compelling Turkish Cypriot authorities and Turkey to take tougher action to protect their interests.

This became evident when on 6 February 2018 Turkish authorities issued a notice to mariners (FA78-0198), reserving for “military training” an area to the south east of Cyprus, including Block 3, that was licenced by the Greek Cypriot side to Eni.

This effectively stopped Eni’s drillship Saipem 12000 that was on its way from Block 6 (Calypso) to Block 3 (Cuttlefish) for exploratory drilling. The bulk of Greek Cypriot Block 3 has also been licenced by the Turkish Cypriot side to TPAO. The Turkish Cypriot side and Turkey are now determined to prevent any further Greek Cypriot activity in the Blocks licenced to TPAO. Turkey is also preventing any activity in its continental shelf.

All of this seems to indicate that the discovery of hydrocarbons has so far further aggravated the Cyprus issue and fuelled maritime and territorial disputes, threatening to destabilise a region already laden with conflict. The “blessing element”, or the gains associated with sharing the prosperity of the hydrocarbons discovery has failed to materialise and cannot therefore alone be regarded as the strong stimulator to break the political stalemate.

Indeed, I am now observing that the fear of disaster – or the “curse element” – may hold better potential to stimulate outside the box thinking on Cyprus. So far, the Greek Cypriot side has been in a protected “comfort zone” inside the box – the status quo. Depending on its severity, the “curse element” may now be challenging the status quo and could stimulate win-win solutions based on a “problem solving” approach.

Below I will list some of the developments I have witnessed recently:

• Hydrocarbons discovery has substantially contributed to Greek Cypriot reluctance to share power and prosperity. This is reflected in the strategy pursued by their negotiators. In the past, Greek Cypriot negotiators supported a strong federal government with extensive competences. Over the last few months Greek Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades has been suggesting a “loose federation” with extensive powers remaining within the two Constituent States, possibly aimed reducing the scope of power and prosperity sharing. There is also talk that in his “exceptional” meeting with Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu in New York last September, he hinted at the possibility of a negotiated two-state solution, meaning separation and no sharing of power and prosperity. It is highly likely that further discoveries of hydrocarbons by Greek Cypriots will spur acceptance of a two-state solution to “save” the economic benefits of its own share of hydrocarbons.

• Rising tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean and the warning of UN Secretary-General that unilateral exploratory drilling could result in renewed escalation[3] is likely to stimulate some “forward looking” third parties (this could include some petroleum companies and UN bodies) to steadily move towards policies of mutually compatible satisfiers and conditionality to prevent further escalations and encourage a win-win agreement on hydrocarbons exploitation for all parties involved.

• Continued unilateralism in Cyprus, the “fait accompli” each side is creating and the fatigue resulting from the perennial uncertainty and risk of non-settlement could by default end up in an outcome that will reflect the realities on the ground: i.e. essentially normalising the status quo.

In conclusion, it is likely that non-settlement, the increasing risk of disaster and fatigue could stimulate or lead to one or a blend of the above possibilities.

In any case, in addition to the intrinsic responsibilities of the Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, Greece and Turkey, important responsibilities rest on the shoulders of third parties in the region, including the UN, EU member states and relevant oil companies.

These actors must explore new and mutually compatible satisfiers to end the unilateralism and risky escalation connected to the hydrocarbons issue in Cyprus and the broader Eastern Mediterranean, working to transform hydrocarbons into a facilitator to resolve disputes rather than an accelerator for further disagreements in the area.

* Mustafa Ergün Olgun is a former Turkish Cypriot negotiator.

[1] Turkey notified the UN on 2 March 2004 and 12 March 2013 regarding the boundary of its continental shelf to the west and south west of Cyprus.

[2] See 11 February 2014 Joint Declaration on Cyprus, http://www.uncyprustalks.org/?p=1749.

[3] UN Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General on His Mission of Good Offices in Cyprus (S/2018/919), 15 October 2018, para. 23, https://undocs.org/S/2018/919.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, February 2019, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

19|17