How Italians View Their Defence? Active, Security-oriented, Cooperative and Cheap

How Italians View Their Defence? Active, Security-oriented, Cooperative and Cheap

Karolina Muti and Alessandro Marrone*

Italians are generally well disposed towards their armed forces, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the prospect of enhanced defence cooperation within the EU. A recent survey, elaborated by the Political and Social Analysis Laboratory (LAPS) of the University of Siena and the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), provides interesting insights on Italian public opinion trends on security and defence matters, Rome’s alliance frameworks and foreign policy priorities.[1]

The vast majority of respondents, independently from their polarised political views, approve of the use of the military for a set of different tasks, demonstrating a somewhat peculiar understanding of the role of Italian armed forces among the public.

The highest consensus (90 per cent) is gathered for the notion that the military should support civil authorities in response to natural disasters. This is followed by intelligence gathering and counter-terrorism operations (88 per cent), and control of maritime routes in the Mediterranean and adjacent seas (84 per cent).

A contribution by the armed forces in the event of national emergencies and extraordinary circumstances (such as a natural disaster) is foreseen by Italian legislation.[2] Yet this is clearly not meant to be the main mission of the military. In fact, according to Italian law the first task of the armed forces is the protection of the state, followed by contributing to international peace and security.[3]

Contributing to a peace-keeping operation enjoys 66 per cent of support, while defending a NATO ally in case of an attack is supported by 59 per cent of respondents. When it comes to ongoing operations, a clear majority approves of Italian military commitments abroad, with percentages ranging from 58 per cent in the case of Lebanon to 52 per cent in the Afghan one.

The fact that Italians tend to approve of these missions is not obvious. During the Cold War, the domestic political landscape was characterised by strong anti-militarist – both left-wing and catholic – currents. However, since the 1990s, a considerable shift has occurred. Italy’s international activism began to increase, particularly through its participation in a growing number of civilian and military operations abroad. As a result, the armed forces became an important asset in the country’s foreign policy, contributing to both international security and the protection of Italian national interests.[4]

In 2018, Rome participated in 42 international missions, with about 6,550 soldiers deployed in different parts of the globe, mainly the Middle East, Africa and Europe.[5] The largest contingents in terms of budget and deployed personnel are located in the Middle East.

Currently Italy contributes with 1,100 soldiers to the international coalition led by the US against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). The UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) involves almost the same number of Italian personnel. Despite the fact that NATO’s Resolute Support Mission in Afghanistan has been radically scaled back, it still remains Italy’s third largest mission, with around 800 troops on the ground. When it comes to Europe’s neighbourhood, the national maritime operation “Mare Sicuro” (Safe Sea) employs 754 personnel with the goal of ensuring maritime surveillance and security in the Mediterranean Sea.[6]

By unpacking the data, one can see that Italy’s public opinion is divided in two blocs when it comes to support for international missions. Citizens who sympathise with parties opposed to the current government led by Giuseppe Conte, including most notably Italy’s centre-left and centre-right parties, tend to support Italy’s participation in international missions by large majorities, 74 per cent and 56 per cent respectively. The current government’s sympathisers, on the other hand, show more reservations on the topic. Among right-wing League party supporters, 48 per cent declare their support for international missions. With regards to Italy’s other governing coalition partner, the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle – M5S), only 34 per cent of voters express their support for such missions.

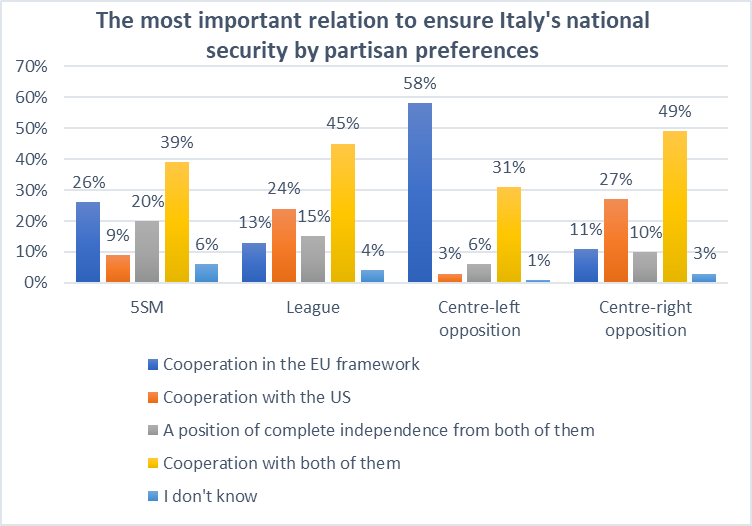

Public opinion is strongly in favour of cooperation with traditional allies on defence and international security, including League and M5S voters, despite the nationalistic and anti-establishment rhetoric of both parties. In fact, a vast majority of respondents claims that cooperation within the EU and/or with the US is the most important bond to ensure national security. In particular, 39 per cent of interviewees want Italy to cooperate on national security with both the EU and US, a further 31 per cent favours cooperation within the Union and about 11 per cent prioritise Washington. Even among M5S sympathisers, support for a completely autonomous stance, independent from both Europe and the US, gathers only 20 per cent consensus, a percentage that decreases further to 15 per cent among League voters.

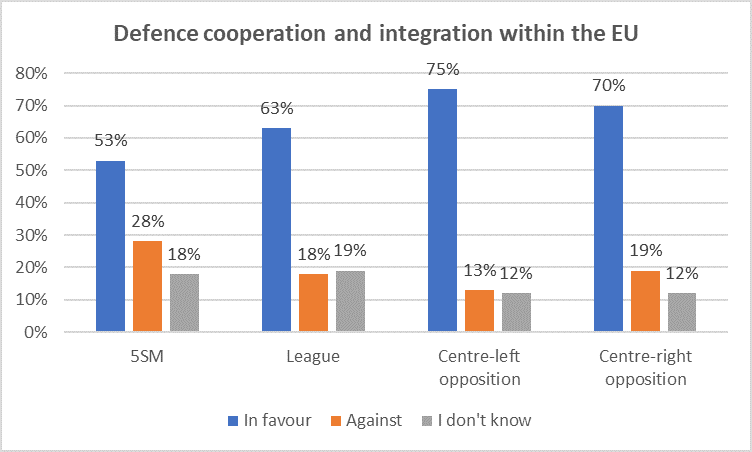

European defence cooperation initiatives also enjoy broad support – 60 per cent – with absolute majorities among both government and opposition sympathisers. This is of particular interest since defence has traditionally been considered a national prerogative within the whole EU integration process.

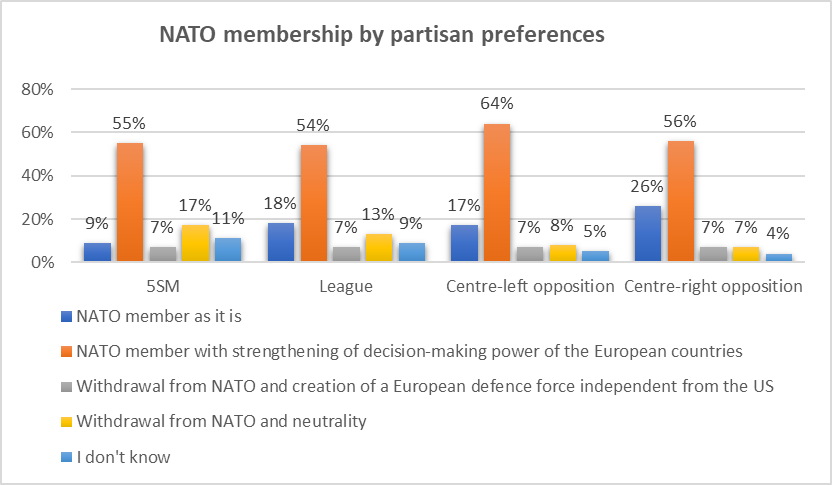

When it comes to NATO, it is worth noting that support for the Alliance remains particularly high, with a 70 per cent overall approval rating, accompanied by widespread support for the prospect of a stronger European pillar inside the Alliance (54 per cent). Again, such a stance is measurable across party lines ranging from 64 per cent of M5S voters to 72 per cent of League ones, up to the 81 per cent and 82 per cent among centre-left and centre-right parties.

Despite the strong approval of Italy’s NATO membership, support to defend a NATO ally that comes under potential attack is, as noted above, considerably lower (59 per cent). Collective defence is not perceived as a priority by public opinion, being among the least preferred tasks for the use of military force. This reflects a traditional Italian understanding about post-Cold War NATO, which emphasizes crisis management, partnership and cooperative security rather than collective defence.

Only 35 per cent of respondents are in favour of increasing military expenditure, whereas 52 per cent are against.[7] Italians, therefore, are supportive of defence cooperation within both NATO and the EU, back European defence initiatives, perceive a vast range of threats and are calling for greater security, but have little appetite for more defence spending.

Defence has never been and will likely not become a top priority for Italy’s government or public opinion. Nevertheless, due to the strong focus on security reflected by Italian voters and the growing instability of the international context, particularly in Africa and the Middle East, there seems to be a fundamental contradiction between the wide range of tasks that Italians want the armed forces to accomplish, and their reluctance to support the necessary means and resource allocation to carry them out.

Understanding these contradictory attitudes is crucial for experts, practitioners and policy-makers if they want to promote a more mature and systematic debate on national security and defence policy in Italy. Misperceptions could stem from a relatively low interest for defence matters among the public, a lack of a proper security and defence culture in Italy, along with a gap in adequate communication between the armed forces and public opinion.

Apparently Italians want to have their cake and eat it too. However, security does not come for free, and should be considered a crucial investment in terms of financial resources, necessary capabilities and commitments to allies.

* Karolina Muti is Junior Researcher in the Security and Defence programmes of the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Alessandro Marrone is Head of the IAI Defence programme and editor of the Documenti IAI series.

[1] LAPS and IAI, “Gli italiani e la Difesa”, in Documenti IAI, No. 19|08 (April 2019), https://www.iai.it/en/node/10228.

[2] Law No. 331 of 14 November 2000: Norme per l’istituzione del servizio militare professionale, https://www.normattiva.it/uri-res/N2Ls?urn:nir:stato:legge:2000-11-14;331.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Piero Ignazi, Giampiero Giacomello and Fabrizio Coticchia, Italian Military Operations Abroad. Just Don’t Call It War, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

[5] Andrea Aversano Stabile, “L’Italia e le missioni oltremare”, in Focus Euroatlantico, No. 9 (July-September 2018), p. 32-42, https://www.iai.it/en/node/9594.

[6] Italian Parliament Research Service, “Autorizzazione e proroga missioni internazionali 2019 - DOC. XXV n. 2 e DOC. XXVI n. 2”, in Dossiers, 13 May 2019, p. 21-22, http://www.senato.it/service/PDF/PDFServer/BGT/01111187.pdf.

[7] The remaining 13 per cent of respondents answered “Don’t know”.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, June 2019, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

19|39