There Is No Green Deal without a Just Transition

There Is No Green Deal without a Just Transition

Luca Bergamaschi*

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015 – whose preamble explicitly refers to the just transition – an important debate has started on how to manage the ecological transition in a fair and orderly way.

The concept of “just transition” is not new. Its essence has always been at the centre of the great industrial revolutions of the past and one of the driving forces behind the birth of modern welfare systems. Without guaranteeing the conditions for social stability – through rights, sustainable working conditions and social protection – it is impossible to maintain the economic and political stability of a state.

Faced with the great transformations of our times, from technology to the need to respond to climate change, it is therefore essential to put the issue of a just transition at centre stage when designing a “Green New Deal”. This is a key necessity to protect and offer a credible alternative to those most affected by change.

Internationally, progress has been made in recent years towards a clear political recognition of the challenge. In 2015, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) developed guidelines for a just ecological transition[1] and more recently new ideas have been developed as part of the work of the ILO’s Commission for the Future of Work.[2] International trade union organisations were the first to take this work forward through, for example, the opening of a dedicated centre at the International Trade Union Confederation[3] and the production of studies and recommendations by its European office.[4] But the highest level of political recognition came from the Declaration of Solidarity and Just Transition of the Heads of State at the opening of COP24 held in Poland (in the Silesian coal region) in 2018.[5]

In essence, the focus has so far been on reconciling decarbonisation and climate adaptation efforts with climate and social justice, through:

- the creation of new quality jobs and inclusive transition processes that safeguard the rights of all;

- building resilience, in particular in infrastructure, to protect groups most exposed to climate impacts, especially in the most vulnerable countries;

- achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement to ensure climate justice for all and intergenerational justice for future generations;

- recognising and addressing in a just and sustainable way the particular challenges faced by specific sectors, regions, cities and communities most vulnerable to change.

The European Commission has now made a first important step forward, by announcing a 1 trillion euro European Green Deal package through the proposal of a Just Transition Mechanism.[6]

At its core there is a Just Transition Fund of 7,5 billion euro established by a new Regulation as well as amendments to the Common Provision Regulation for all EU funds. This is complimented by a reshuffling of existing funds from Cohesion Policy to a total of 30-50 billion euro. There will also be a dedicated just transition scheme under InvestEU to mobilise up to 45 billion euro of investments to attract private inflows. The last and third pillar is a public sector loan facility under the European Investment Bank backed by the EU budget to bring in another 25-30 billion euro. Negotiations with the European Parliament and the Council on both the new Regulation and the funding will run for the whole of 2020.

Beyond money and as far as technical assistance is concerned it is important to note the role of the Platform for Coal Regions in Transition which was set up in 2017 with the aim of supporting member states and regions in modernising their economies and preparing them for the structural transition. Currently 18 coal regions are participating in the initiative.[7]

While there is increasing attention to the concept of just transition globally and in Europe, there is a fundamental lack of debate in Italy despite placing a Green Deal at the top of the political agenda. The debate is focused on the positive creation of opportunities such as new jobs and industries without however reflecting on the consequences that decarbonisation has on society and industry.

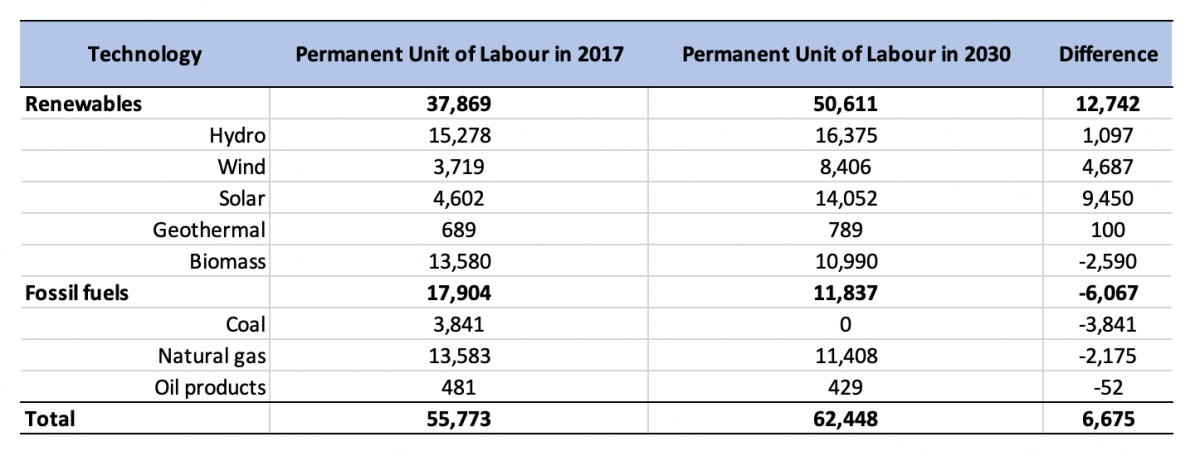

As the draft National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP)[8] shows, there are important occupation changes to be expected over the next decades. While the renewable sector is expected to add substantial numbers of new jobs, the fossil fuels sector (in particular the coal and gas sectors) are expected to lose over 6 thousand jobs (see Table 1).[9]

Table 1 | Permanent employment by source in 2017 and 2030 as a result of the evolution of the power generation stock according to the NECP scenario

Source: Italian Government, Draft Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan, cit., p. 236.

Moreover, looking into the future, one can expect further disruptions as the 2030 emission targets will most likely increase as Europe enhances its climate ambitions. We can also expect similar trends in energy-intensive industries, such as steel, cement and aluminium, and the car manufacturing industry where technological change, such as electric vehicles, are set to revolutionise the employment landscape.

These types of assessments are therefore vital to understand the scale of the problem and identify critical situations before they become unmanageable. Governments, industry leaders, associations and trade unions need to address the issue of employment transition through designing and implementing social and economic plans that can prepare for the coming change. Failing to do so will lead us to a disorderly transition where the most vulnerable communities will suffer from job losses, emigration – in particular of the youth – and loss of well-being.

There are already signs that point in this direction. The emblematic case of ex-ILVA in the southern Italian city of Taranto – the biggest steel industry complex in Europe – shows that simply responding to emergencies is no longer an option. Without strategic planning and long-term investment for decarbonising industry in a socially sustainable way there will be little future for Italy’s energy-intensive and car industry in a competitive, globalised and zero-carbon market.

While there is a dire lack of vision in the political and industry space, the Italian trade unions (CGIL, CISL and UIL) have provided a new refreshing vision for the just transition in Italy.[10] They are in favour of greater climate ambitions (through increasing the EU 2030 target to 55 per cent and reaching climate neutrality by 2050) and to increase the deployment of renewables, energy efficiency and electric mobility.

This will encourage “paths of democratic participation in the planning and negotiation of just transition measures” and “to integrate the fight for climate justice into all confederal and sectoral bargaining policies”.[11] Support along these lines was also expressed by the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development through a manifesto of priorities for the just transition.[12] On the private sector front, it is worth noting the effort of Enel’s Futur-e initiative that aims at revitalising 23 thermoelectric power plants and a former mining site.[13]

It is clear that no institution can manage the transition alone. In order to provide strategic guidance and the strongest political mandate for action, the establishment of a new permanent unit under the Prime Minister’s Office in charge of delivering the Green Deal could be explored. As part of this unit, special attention should be devoted to the issue of the just transition. In order to ensure participation and inclusion, a regular dialogue is needed between trade unions, industry associations and civil society in order to find common policies and tailored-made solutions for each case.

Finally, as Italy builds its long-term strategy with the aim of achieving climate neutrality by 2050, it is essential to carry out a thorough assessment of the impact that decarbonisation will have on the job market and across all industries as well as making sure that enough European funds are dedicated to just transitions plans.

* Luca Bergamaschi is Associate Fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

Paper prepared in the framework of the project “Delivering Italy’s coal phase out – Policy options and international implications”, conducted by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) in collaboration with the European Climate Foundation (ECF), December 2019.

[1] ILO, Guidelines for a Just Transition Towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All, 2015, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/WCMS_432859.

[2] ILO website: Global Commission on the Future of Work, https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/future-of-work/WCMS_569528.

[3] International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC) website: Just Transition Centre, https://www.ituc-csi.org/just-transition-centre.

[4] European Trade Union Institute (ETUI) website: Sustainable Development & Industrial Policy, https://www.etui.org/Topics/Sustainable-Development-industrial-policy.

[5] COP24, Solidarity and Just Transition Silesia Declaration, 3 December 2018, https://cop24.gov.pl/presidency/initiatives/just-transition-declaration.

[6] European Commission, Financing the Green Transition: The European Green Deal Investment Plan and Just Transition Mechanism, 14 January 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_17.

[7] European Commission website, Coal Regions in Transition, last updated 20 January 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/node/134582#the-platform-for-coal-regions-in-transition.

[8] For links to the draft Italian NECP in the original language and translated into English, alongside the Commission’s review of it, including recommendations for improvement, see the European Commission website: National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs), https://ec.europa.eu/energy/en/topics/energy-strategy-and-energy-union/national-energy-climate-plans.

[9] Italian Government, Draft Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan, 31 December 2018, p. 236-237, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/ec_courtesy_translation_it_necp.pdf.

[10] CGIL, CISL, UIL, Per un modello di sviluppo sostenibile, 26 September 2019, http://www.cgil.it/?p=118003.

[11] Ibid., p. 6.

[12] Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS), Priorità per una transizione ambiziosa, giusta e sostenibile, 29 May 2019, https://asvis.it/home/46-4148.

[13] See Enel website: Futur-e, https://corporate.enel.it/en/futur-e.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, January 2020, 4 p. -

In:

-

Issue

20|01