How Democratic Is the “World’s Largest Democracy”?

When referred to in the media, India almost invariably gets the attribute “the world’s largest democracy”. Official documents and speeches by western leaders – such as the US National Security Strategy[1] or the India-Italy Joint Statement[2] during Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s recent visit to New Delhi – also describe India as a beacon of democracy in an autocratising world. While this is partly a historical legacy due to India’s remarkable ability to establish and consolidate as a democracy after the end of colonisation, it also reflects the country’s importance as a strategic partner for western democracies in an effort to contain the rise of China. However, today, very few analysts would still describe India as a full democracy.

Sliding towards an electoral autocracy

The latest V-Dem report[3] – which measures the quality of democracy worldwide – is yet another reminder that India seems to have turned into an “electoral autocracy”, a hybrid regime where free and (somewhat) fair elections are still held, while the government employs a variety of informal and formal mechanisms of coercion and control which tilt the playing field in its favour and dramatically erode freedom and democratic practice. In other words, India still holds democratic elections, but is closer to an autocracy between them.

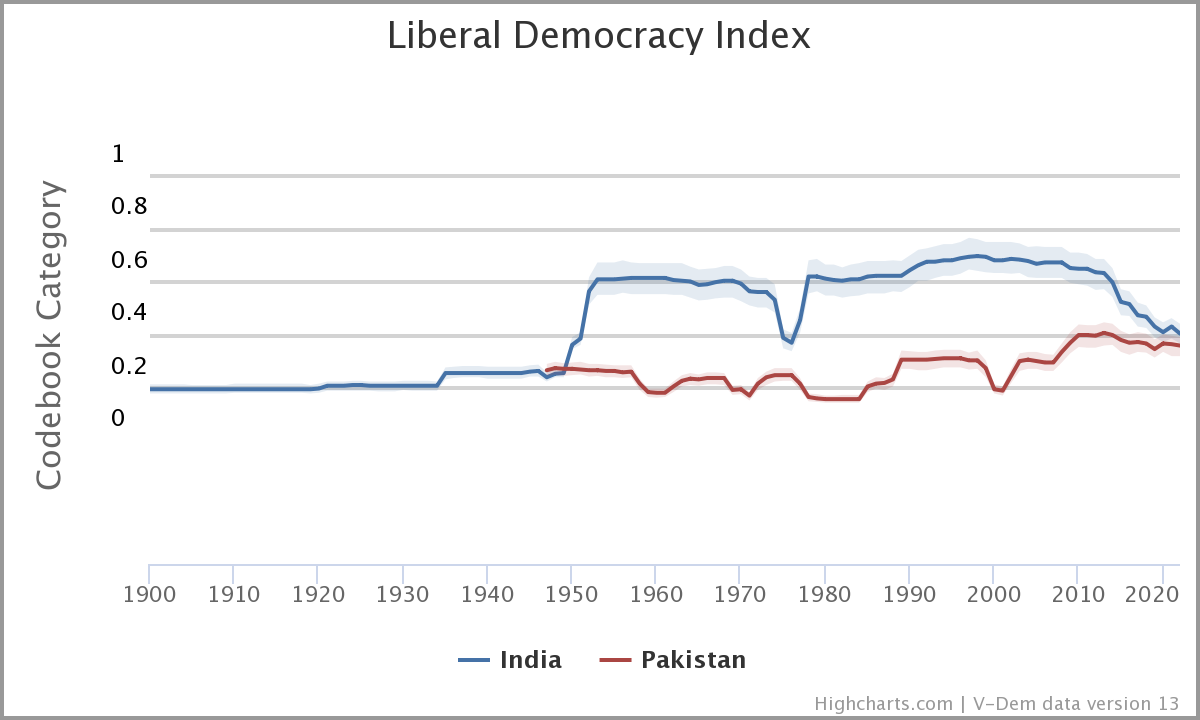

The V-Dem index is an attempt to “quantify” the quality of democracy. While the measure is imperfect and, in any given year, hardly meaningful per se – it is hard to tell what is the difference for a country to be 68 or 72 democratic – it does capture change over time effectively. Figure 1 shows V-Dem’s most comprehensive variable (the Liberal Democracy Index) for India and Pakistan.

Figure 1 | Liberal Democracy Index, India and Pakistan 1900–2022

Source: V-Dem Institute, Variable Graph, https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/VariableGraph.

Three things stand out. First, India and Pakistan’s most recent values (0,31 and 0,26, respectively), are broadly similar. Second, India’s democratic quality is almost as low as during the Emergency regime (1975–77), when Indira Gandhi’s government suspended elections, jailed opposition politicians and imposed censorship. Third, there has been a steep decline in the quality of democracy in India since the advent of Narendra Modi as Prime Minister in 2014. Other indexes such as Freedom House[4] or the Economist Intelligence Unit[5] also pushed India out of the (increasingly small) liberal democracy club. But what are the key reasons behind India’s democratic backsliding?

Undermining the independence of the judiciary and watchdogs

The current regime changed India’s political system in at least three ways. First, the independence of key institutions such as the Supreme Court and the Election Commission of India (ECI), which have long enjoyed a reputation as effective constraints on the power of the executive, has been deeply compromised. Through selective appointments, outright intimidation and post-retirement perks to members, the Indian government has been able to profoundly shape the functioning of the country’s most important watchdogs.[6] The Supreme Court has repeatedly ruled in favour of the government in highly controversial cases, such as those involving Modi’s right-hand man and Home Minister Amit Shah or the alleged corruption surrounding the purchase of Rafale jets from France. In other cases, the Supreme Court has simply postponed dealing with cases with profound political implications for the ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), such as the one probing the legality of the electoral bonds, an instrument introduced by the Modi administration to fund political parties.[7] Similarly, the ECI has been accused repeatedly of closing both eyes in front of quite blatant violation of electoral regulations by the ruling BJP.[8]

Perhaps even more crucially, investigative agencies have been unleashed to target opposition politicians, journalists and social activists. Since 2014, there has been a fourfold increase in the number of cases opened by the Enforcement Directorate (which investigates financial irregularities) against politicians, 95 per cent of which belonged to the opposition.[9] Additionally, the Parliament and even the Cabinet have been functioning mostly as rubber-stamp institutions, as all key legislation and executive orders have been centralised in the Prime Minister’s Office. In one instance, the words of the leader of the opposition, Rahul Gandhi, were expunged from the official transcript.[10] Gandhi’s comments on the proximity of the Prime Minister to India’s richest man, Gautam Adani, had been quite embarrassing for the government.

Cracking down on civil liberties

Second, the government has cracked down on civil liberties, particularly freedom of expression and minority rights. The V-Dem variable measuring the former is now significantly lower than in neighbouring Pakistan. While the recent decision by the Indian government to first ban a BBC documentary on Narendra Modi and then send the Enforcement Directorate to raid the BBC offices made headlines,[11] there have been many less sensational attacks on freedom of expression over the last few years. These included the incarceration under draconian colonial-era laws of journalists, students and civil rights activists;[12] the action of investigative agencies against critical media;[13] the inclusion into the no-fly list of prominent activists, who have been impeded from leaving the country;[14] and a crackdown on civil society organisations such as Greenpeace and Amnesty International (both of which shut most of their India operations).[15] In March 2023, several people were arrested for exposing banners in Delhi asking for the ousting of Prime Minister Modi, while Rahul Gandhi was sentenced to two years in prison (and consequently disqualified as a Member of Parliament) by a Gujarat court (Modi’s home state) for alleged defamation of the Prime Minister.[16]

In parallel, minority rights, in particular those of Muslims (about 15 per cent of the population) have been profoundly eroded. The long list of abuses includes what three UN Special Rapporteurs called “collective punishment” in the form of demolitions of Muslim properties;[17] condoning of religious murders by the authorities;[18] formal partnerships between the police and violent Hindu vigilante groups;[19] and the introduction of formal forms of religious discrimination, such as a new citizenship law that excluded Muslim refugees from gaining citizenship.[20] According to Article 14, an investigative website, the proportion of Muslims accused of sedition increased from 15 per cent on average (2010–14), just above their proportion in the total population, to 30 per cent (2014–20).[21] Some authors in fact began describing India as an “ethnic democracy” or an “ethnocracy”, to highlight the increasingly pronounced Hindu character of the Indian state.[22]

Free elections, but how fair?

Third, the electoral process itself has been compromised, to the point that it is even questionable whether India still meets the very minimum requirement for a democracy, namely free and fair elections.[23] To be clear, elections remain free, but their fairness is a question mark. Not only is the ruling party able to shape the media narrative through a combination of sticks and carrots (like lucrative government advertising); but a newly introduced system to fund political parties (the electoral bonds, EB) perhaps decisively tilted the playing field in favour of the ruling party. The BJP bagged 67 per cent of the total funds donated since 2018 (the second most-funded party, the Indian National Congress, just got 11 per cent). More crucially, the EB allow the donor to remain anonymous, except for the government, which can access data through the publicly-owned State Bank of India.[24] Not coincidentally, V-Dem’s “clean election index” for India has also dropped over the last few years, particularly since the introduction of the EB in 2017.

Looking ahead

Two concluding notes of caution are in order. First, India is not Russia or China. Importantly, extensive pockets of freedom still exist. The very fact that this commentary could be written drawing primarily on India-based sources is a testament to that. But the appellative “largest democracy in the world” is a relic of a past that does not conform to the reality on the ground anymore. Second, Prime Minister Narendra Modi remains genuinely popular. Prime Minister Meloni mentioned during her visit to India that Modi is the most popular leader in the world, and international and Indian opinion polls back that up.[25] Modi’s popularity, combined with the severe democratic erosion that has occurred in recent years, should make the general election next year a cakewalk for the ruling BJP.

In all probability, the BJP is here to stay. And India seems to be too important a partner in the Indo-Pacific (as well as in economic terms) for western governments to even mildly criticise the current regime. Significantly, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak hardly defended the BBC after the Modi government raided its India offices. This seems to be the “cost of doing business” with today’s India: going along with the “world’s largest democracy” mantra and uncritically accepting India’s own claim to be “the mother of democracy”, as its G20 presidency slogan says.

Diego Maiorano is Senior Assistant Professor at the University of Naples “L’Orientale”, Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), National University of Singapore, and Research Associate at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] White House, National Security Strategy, October 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

[2] India-Italy Joint Statement India-Italy Joint Statement during the State Visit of the President of the Council of Ministers of the Italian Republic to India, New Delhi, 2 March 2023, https://www.governo.it/en/node/21954.

[3] Evie Papada et al., Democracy Report 2023. Defiance in the Face of Autocratization, Gotenburgh, V-Dem Institute, 2023, https://www.v-dem.net/publications/democracy-reports.

[4] Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2023. Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy, Washington, March 2023, https://freedomhouse.org/node/5907.

[5] Economist Intelligence Unit, Democracy Index 2022, London, 2022, https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2022.

[6] Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India. Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy, Princeton/Oxford, Princeton University Press, 2021.

[7] Manu Sebastian, “How Has the Supreme Court Fared During the Modi Years?”, in The Wire, 12 April 2019, https://thewire.in/law/supreme-court-modi-years.

[8] Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India, cit.

[9] Deeptiman Tiwari, “Since 2014, 4-fold Jump in ED Cases against Politicians; 95% Are from Opposition”, in The Indian Express, 21 September 2022.

[10] Liz Mathew, “Parts of Rahul Gandhi’s Parliamentary Speech Expunged: What Does This Mean and When Does This Happen?”, in The Indian Express, 9 February 2023, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-politics/rahul-gandhi-parliament-expunged-8432402.

[11] Mujib Mashal, “Indian Tax Agents Raid BBC Offices after Airing of Documentary Critical of Modi”, in The New York Times, 14 February 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/14/world/asia/india-bbc-tax-raid.html.

[12] Priyam Marik, “How India Is Silencing Its Students”, in The Diplomat, 14 October 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/10/how-india-is-silencing-its-students.

[13] “India’s Proud Tradition of a Free Press Is at Risk”, in The New York Times, 12 February 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/12/opinion/modi-bbc-documentary-india.html.

[14] Bilal Kuchay, “Aakar Patel: Amnesty Official Barred from Leaving India”, in Al Jazeera, 6 April 2022, https://aje.io/rz6fk6.

[15] Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Ben Doherty, “Amnesty to Halt Work in India Due to Government ‘Witch-Hunt’”, in The Guardian, 29 September 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/p/fvqev.

[16] Aniruddha Dhar, “Rahul Gandhi Disqualified as Lok Sabha MP after Surat Court Verdict”, in Hindustan Times, 24 March 2023, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/-101679647469485.html.

[17] United Nations Human Rights Council, Communication to India (AL IND 5/2022), 9 June 2022, https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=27324.

[18] “Union Minister Jayant Sinha Garlands 8 Lynching Convicts”, in Times of India, 8 July 2018, http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/64901863.cms.

[19] Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India, cit.

[20] Madhav Khosla and Milan Vaishnav, “The Three Faces of the Indian State”, in Journal of Democracy, Vol. 32, No. 1 (January 2021), p. 111-125, DOI 10.1353/jod.2021.0004.

[21] Author’s calculations based on the sedition database, accessible here: https://sedition.article-14.com.

[22] Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India, cit.; Indrajit Roy, “India: From the World’s Largest Democracy to an Ethnocracy”, in The India Forum, 17 August 2021, https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/india-world-s-largest-democracy-ethnocracy.

[23] For further details see Diego Maiorano, “Democratic Backsliding Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic in India”, in EUI Policy Briefs, No. 2022/02 (January 2022), https://hdl.handle.net/1814/73590.

[24] Association for Democratic Reforms, Electoral Bonds and Opacity in Political Funding, 6 January 2023, https://adrindia.org/sites/default/files/Background_Note_Electoral_Bonds_Nov_2022.pdf.

[25] Morning Consult website: Global Leader Approval Ratings, https://morningconsult.com/global-leader-approval.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, March 2023, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

23|15