Chinese Banks and Foreign Owned Subsidiaries Eye Latin American Markets: A New Challenge for the US?

Chinese Banks and Foreign Owned Subsidiaries Eye Latin American Markets: A New Challenge for the US?

Nicola Bilotta*

China’s “going global” strategy is making inroads in Latin America, where Beijing has strengthened its political and economic footprint as Washington scrambles to remedy its declining influence and soft power.

As the US retreats from its lead role in support for globalization, China is doubling down on its internationalization strategy. Beijing is presently in talks with Mercosur, the South American trade bloc, to establish a free-trade agreement in response to the US’s growing protectionism.[1]

China’s emerging status in Latin America is rooted in increased trade, foreign direct investment (FDI) and infrastructure projects. Despite a burgeoning effort to understand the implications of growing loan commitments by China’s two major policy banks in the region – the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China –, few have focused on the recent expansion of Chinese commercial banks and their foreign owned subsidiaries (FOS) in Latin America.[2]

The establishment of FOSs is not a marginal phenomenon. They represent the backbone of international economic activities, as the presence of foreign owned banks or subsidiaries in overseas countries tends to follow the increased commitment of their corporate and retail customers.

This is particularly true for the three biggest Chinese state-owned banks – the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), Bank of China (BoC) and the China Construction Bank (CCB) – which have traditionally promoted the internationalization of Chinese businesses and of the Yuan in the global economy.[3]

China’s first FOS in Latin America was established in Panama by the BoC in 1994. Despite this early entrance, no other Chinese FOS was established in the region until 2008. In contrast, between 2009 and 2017, no less than seven Chinese FOS have opened in five different Latin American countries.[4] This expansion has occurred by acquiring pre-existing domestic banks or by establishing new financial institutions.

The spread of Chinese FOS in Latin America follows specific economic interests determined by an increase of trade volume and FDI flows. Today, China has become the top trade partner for an increasing number of Latin American countries, reducing the US’s traditional commercial dominance in the region.[5]

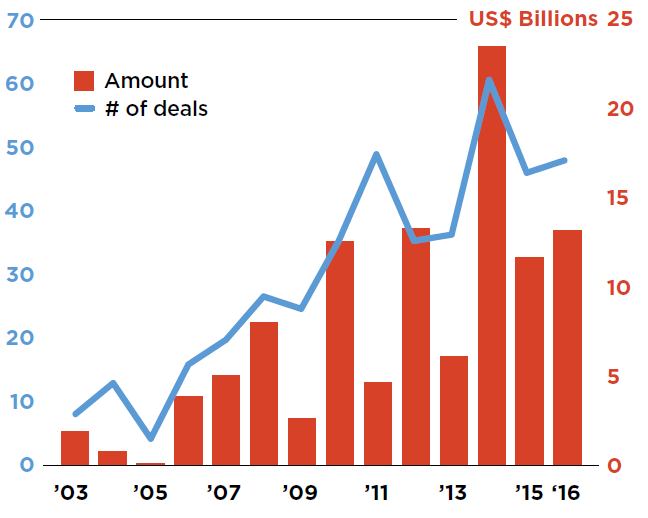

China’s growing influence in Latin America is also reflected by the impressive growth of FDI flows. From 2003 to 2007, the aggregate figure of Chinese FDI in the region was around 5.592 billion US dollars. However, since 2008 the region recorded a drastic growth of Chinese FDI, reaching more than 43.885 billion US dollars in the period 2008-2017.[6]

Figure 1 | Annual FDI flows from China to Latin America

Source: Rolando Avendano, Angel Melguizo and Sean Miner, Chinese FDI in Latin America, cit., p. 1.

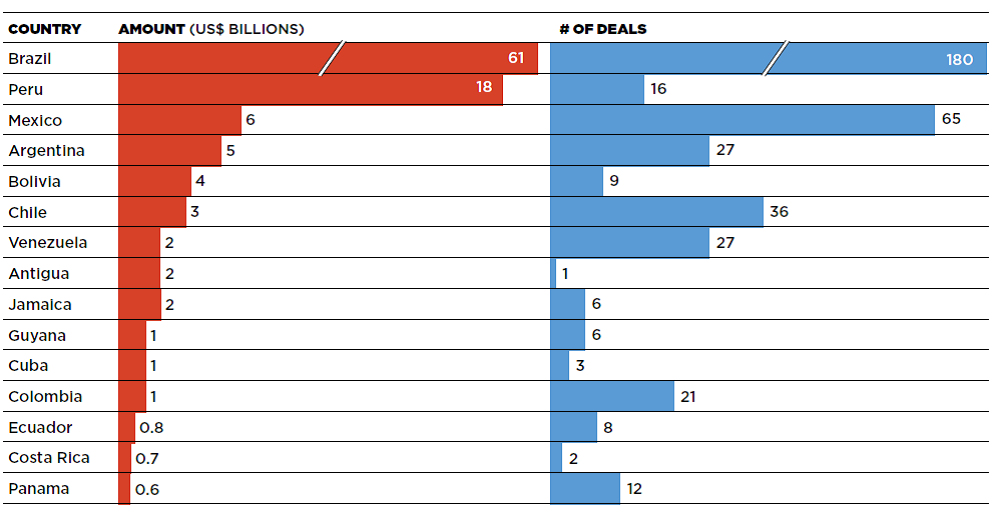

Figure 2 | Chinese FDI in Latin America, by country (2003-2016)

Source: Rolando Avendano, Angel Melguizo and Sean Miner, Chinese FDI in Latin America, cit., p. 7.

The establishment of Chinese FOS in Latin American countries closely coincides with the amount of Chinese FDIs in these national contexts. Brazil, for instance, received about 57 per cent of total Chinese FDI across the region between 2003 and 2016 leading to the early establishment of a Chinese FOS in the country.[7] Today, Brazil is the only Latin American country that hosts a subsidiary of each of China’s “Big Three” banks. Similarly, the establishment of FOS in other countries of the region was generally preceded by a large increase of Chinese FDI inflows to that country.

In parallel with the expansion of Chinese FOSs in Latin America, Western international banks have been redesigning their global strategies and exposure. Since the global financial crisis, several Western, particularly European, banks have retreated from South America altogether.[8] This provided Chinese banks with a golden opportunity to expand their operations. In 2017, China’s eight FOS in the region recorded 15.739 billion US dollars in assets, 7.684 billion US dollars in loans and 8.436 billion US dollars in deposits.[9]

A comparison of financial data pertaining to Chinese FOSs with those of the top three US FOS banks active in Latin America – Citibank, Bank of America and JP Morgan Chase – can help to understand the growing leverage of Chinese banks in the region. Comparisons are possible in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico and Peru, countries that host both US and Chinese FOSs.

US banks undeniably enjoy a more diversified footprint in the Latin American market compared to a relative newcomer such as China. However, what stands out from this comparison is that US FOSs are more focused on trading activities – 35.6 per cent and 35.5 per cent of their total assets are financial products and gross loans, respectively – while the core business of Chinese FOS is concentrated in lending and borrowing – with 42.7 per cent and 24.6 per cent of their total assets accounting for gross loans and financial products respectively.

If one excludes Mexico from the comparison – which due to geographical proximity enjoys close economic ties with the US –, only 18 per cent of US FOSs assets are allocated to lending, whereas the Chinese figure hovers around 43.5 per cent.

This reflects the different stages of the US and Chinese economies and, consequently, the divergent functions of their respective international banks. Whereas US banks pursue their own interests and those of their private shareholders, state-owned Chinese banks serve Beijing’s political goals, providing advantageous financial support to Chinese companies and citizens abroad.

Latin America’s so-called “Left-Turn” since the 2000s, has provided fertile ground for China’s expanding geopolitical and economic aspirations. Regional left-wing governments have sought to disengage and rebalance their relationships away from the US, seeking new partnerships and business rapports. While Europe has also sought to take advantage of these developments, and has seen its economic and commercial ties grow with a number of Latin American countries, trade relations are hamstrung by the complex bureaucratic decision making in Brussels and the effects of the 2008 global economic crisis.

China’s centralized decision making and growing economy have instead provided Beijing with an opening to consolidate its credibility and influence. China’s traditional emphasis on the principle of non-interference and its general disinterest in political conditionality on its trade and development assistance has no doubt helped Beijing in these efforts.

While China’s demand for raw materials – which in part fueled Latin America’s economic boom from 2002 to 2012 – has now slowed, Beijing is today moving beyond these sectors. Since 2013, Chinese firms have targeted the service industry, dramatically increasing their investments in transport, finance, ICT and alternative energy – which represented more than 50 per cent of total FDIs in the period 2013-2016.

Beijing’s long-term goal is that of gaining geopolitical influence in Latin America, and indeed a number of regional governments have already begun to look to Beijing as a valuable counterbalance to the Trump administration. Consolidating China’s presence in new export markets, promoting the internationalization of Chinese companies and seeking new investment opportunities in key infrastructure and commercial sectors are elements that in the long run are also likely to buy China political and diplomatic influence in the region, causing some concern in the US.

In what may have been a rather unfortunate comment, former US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson praised the US’s 19th century Monroe Doctrine before kicking off a tour of Latin American countries in early February 2018. Claiming that the Doctrine is “as relevant today as it was the day it was written”, the Trump administration official went on to warned about China’s “imperial” ambitions in Latin America.[10]

With only 16 per cent of Latin Americans’ approving of Trump’s performance as US president according to a recent Gallup poll,[11] the US is facing considerable obstacles to its influence in its “backyard”. Unless Washington constructs a new paradigm of mutual cooperation and respect with its regional neighbours, the Chinese alternative may well end up gaining further currency across the region, perhaps even contributing to a further heightening of tensions between Washington and Beijing.

Against this backdrop, Europe appears as a distant and relatively passive spectator. While a number of EU member states do have significant economic interests in Latin America, and aggregate European FDI inflows are still today greater than those originating from China,[12] it appears as if the region is shedding some of its previous importance for the EU. Negotiations for a EU-Mercosur free trade agreement, for examples, have been ongoing for twenty years with little to show in terms of tangible progress.

Distracted by the Union’s socio-economic and political challenges, EU member states may be losing an important opportunity to improve their positioning in the region, even potentially offering Latin American countries a valuable external partner capable of offsetting some of the pressures of China’s growing presence in Latin America.

Important in this regard is to restore the EU’s credibility as a reliable international actor that is capable of delivering on its promises. Ultimately, while China has now overtaken Europe as Latin America’s second commercial partner, EU member states would do well to reenergize their focus towards the region, building on Europe’s history of collaboration to establish stronger bilateral and multilateral relations with Latin American states.

* Nicola Bilotta is junior researcher at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] Mercosur countries include: Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela. See, Naoyuki Toyama, “China and South Korea Seek Free Trade Deal with Mercosur”, in Nikkei Asian Review, 22 April 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/China-and-South-Korea-seek-free-trade-deal-with-Mercosur.

[2] A FOS is a partially or a wholly owned company that is part of a larger corporation with its headquarters in another country. FOS operates under the laws of the country in which it operates.

[3] ICBC, CCB and BoC are the biggest commercial banks of the world. As of December 2017, they recorded more than 10 trillion US dollars in total assets.

[4] ICBC has a FOS in Argentina (2012), Brazil (2013), Peru (2013) and Mexico (2014); BoC in Panama (1994) and Brazil (2009); CCB in Brazil (2013) and Chile (2016).

[5] Carlos Torres and Randy Woods, “China Is Boosting Ties in Latin America Trump Should Be Worried”, in Bloomberg, 3 January 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-01-03/china-is-boosting-ties-in-latin-america-trump-should-be-worried.

[6] Rolando Avendano, Angel Melguizo and Sean Miner, Chinese FDI in Latin America: New Trends with Global Implications, Washington, Atlantic Council, June 2017, p. 1, http://publications.atlanticcouncil.org/china-fdi-latin-america.

[7] Ibidem, p. 7.

[8] In the past years, HSBC, the biggest European bank, ended its activities in Colombia and Brazil, while Deutsche Bank closed its FOSs in Chile and Peru. Similarly, BBVA and Barclays closed their FOSs in Brazil, DNB has retreated from Chile and Standard Chartered has withdrawn from Peru.

[9] The author calculated the data from FOS’ financial statements for the fiscal year 2017 except for CCB Brazil of which the financial data for the fiscal year 2017 were unavailable. The figures are converted in US dollars using the currency exchange rate at 31 December 2017.

[10] Robbie Gramer and Keith Johnson, “Tillerson Praises Monroe Doctrine, warns Latin America of ‘Imperial’ Chinese Ambitions”, in Foreign Policy, 2 February 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/02/02/tillerson-praises-monroe-doctrine-warns-latin-america-off-imperial-chinese-ambitions-mexico-south-america-nafta-diplomacy-trump-trade-venezuela-maduro.

[11] Elizabeth Keating, “Outlook Grim in Latin America for Relations Under Trump”, in Gallup News, 24 January 2018, https://news.gallup.com/poll/226193/outlook-grim-latin-america-relations-trump.aspx.

[12] Nolte Detlef, “China Is Challenging but (Still) Not Displacing Europe in Latin America”, in GIGA Focus Latin America, No. 1 (February 2018), https://www.giga-hamburg.de/en/node/21171.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, October 2018, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

18|61