Taking Back Control? The UK Parliament and the Brexit Withdrawal Negotiations

Taking Back Control? The UK Parliament and the Brexit Withdrawal Negotiations

Tim Oliver*

• Parliament has been the site of intense arguments and differences over what the UK’s vote to leave should mean, not least when it comes to approving the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement. The deep divisions in the Conservative and Labour parties especially, reflect similar divisions in British society.

• Parliament has been somewhat more united and effective in its scrutiny of Brexit, although the centralised and secretive nature of the UK state remains a big obstacle.

• Deep divisions and uncertainty over the direction of Brexit, especially over the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement, has given rise to suggestions, albeit constitutionally controversial ones, that Parliament could take control of the process by directing the executive in terms of policy.

Britain’s vote to withdraw from the EU triggered a series of debates about the nature of the British state and political system, not least the role of the UK parliament. While focus has been on UK-EU negotiations, institutional developments within the UK have been equally important to anybody wishing to understand Brexit.

Brexit is as much about what sort of country Britain wants to be as it is about UK-EU relations. While the Vote Leave campaign urged the British people to “take back control”, it is unclear where control would be taken back to or who it would be taken from. This is because there are conflicting understandings of where power lies in the UK.

A traditional view of Britain’s uncodified constitutional setup is that all power rests in the Westminster parliament. However, not only is this questioned by the power of devolved parliaments or the power of the people through direct democracy, i.e. a referendum. There are also long-standing questions about the distribution of power in parliament, especially between the executive and the House of Commons.

As a result, parliament’s role has at times been at the heart of proceedings, at others it has relied on the judiciary to clarify its role, while in others still it has been the backdrop for Conservative or Labour party infighting.

This mix of roles is largely reflective of the divisive nature of Britain’s Brexit debate, which is set to continue into the foreseeable future. Parliament’s role has been in constant flux, as demonstrated by the three roles it has played in the negotiations: approving, scrutinising and instructing Brexit.

Approving Brexit

Having approved the holding of a referendum, it was unclear whether parliament was then bound by the result. The British government argued that implementing withdrawal could be done through Royal Prerogatives, powers government wields without much parliamentary oversight, especially in foreign policy. Anti-Brexit campaigners challenged this reading, with Britain’s Supreme Court ruling in January 2017 against the British government.[1] While parliament did vote the next month to trigger article 50, the episode pointed to a long-standing pattern of executive control in British politics.

Tensions between the executive and legislature became clearer when the Conservative Party lost its majority in the 2017 general election. The Conservatives were able to hold onto power thanks to a confidence and supply arrangement with the ten MPs of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). Despite this, the EU Withdrawal Act 2018 gave parliament a defined role in approving any deal with the EU and in scrutinising and approving any course of action in the event of there being no agreement.

This led the British government to promise parliament a “meaningful vote” on Brexit, one that would be more than simply rejecting or accepting any agreement put forward.[2] This inevitably raised questions about how MPs would vote.

Nearly three quarters of MPs voted Remain in the 2016 referendum.[3] In the 2017 general election both the Conservative and Labour parties ran on commitments to honour the Leave vote, but a large number of MPs on all sides remain opposed or uneasy with such an outcome. At the same time, a significant number of Conservative MPs, some Labour MPs and all DUP MPs back Leave, including, for some, a no deal Brexit.

For this reason, the British government faced significant opposition from all sides when, in late 2018, it put forward the Withdrawal Agreement it had concluded with the EU. This was followed the next day by a Conservative party vote of no confidence in Theresa May’s leadership, a vote brought about by Leave supporting Conservative MPs angered by the agreement. When, on 15 January 2019, the government finally put the deal to the House of Commons it was rejected by 432 to 202, the largest defeat suffered by any British government in modern history.[4] Despite this, Theresa May’s government survived a motion of no confidence tabled by the Labour party the next day.

Following the government’s defeat, the executive attempted cross-party talks to find a way forward. However, it soon became clear that talks would go nowhere. This in part reflects the majoritarian nature of politics in the House of Commons where a single party system of governing has long prevailed. Consensus politics between parties, as found elsewhere in Europe and in many other democracies, does not come easy to the House of Commons.

The struggle to find a way forward has been made harder because British politics – and therefore the politics of the House of Commons – has since the June 2016 referendum been defined by a fight to define the Brexit narrative, i.e. what the British people meant when they voted Leave and how this should be delivered. This has paralysed parliament, the government and British politics more broadly.

Scrutinising Brexit

Parliament has succeeded in scrutinising the handling of Brexit by the British government, which has a long-standing reputation for being centralised and secretive.

In late 2017, thanks to the use of admittedly arcane parliamentary procedures, the House of Commons successfully compelled the British government to reveal more than 58 internal government studies on the economic effects of Brexit.[5] Ministers had referred to such studies but had refused to share them publicly.

Parliament’s vote soon revealed that ministers had been exaggerating, perhaps even being economical with the truth, about the degree of preparation for Brexit. More recently, the British government refused a parliamentary vote for the legal advice surrounding the UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement to be made public. The government did not release the advice until the Commons voted to find it in contempt of parliament, something that has not happened for over a hundred years.[6]

MPs have also worked to ensure they play a prominent role in scrutinising changes to UK laws brought about by Brexit. The EU Withdrawal Act 2018 allows the British government a range of what are known as Henry VIII powers, which allow it to amend or repeal parts of primary law through secondary legislation.

The government argued this was necessary to deal with the large number of adjustments Brexit would bring about to British law. However, MPs and Lords expressed deep concerns that this would translate into “excessively wide law-making powers” with “insufficient parliamentary scrutiny”.[7] As a result, the House of Commons European Statutory Instruments Committee was created, which in addition to the Lords Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee, will examine proposed changes and decide whether MPs and Lords should debate and potentially vote on them.

Finally, in January 2019, as part of her efforts to find a way forward over the Withdrawal Agreement, Theresa May promised there will be a more “flexible, open and inclusive” approach to the role of parliament in future negotiations over a new UK-EU relationship.[8] However, it remains unclear to what extent this will be honoured without MPs having to fight for it.

Instructing Brexit

Brexit has raised some unique questions about the ability of parliament to instruct government. Traditionally the role of parliament, especially in international negotiations, has been to react to the executive instead of defining what policy should be.

However, in several House of Commons defeats for the government in December 2018 and January 2019, MPs voted to amend the process by which they would respond should they reject a proposed withdrawal agreement proposed by the government.[9]

In the event of parliament rejecting an agreement, the government usually has 21 days to present a plan to MPs on what to do next. Parliament voted to shorten this to 3 days, limiting Theresa May’s options. Normally, the Commons would vote to take note of what the government then proposes. However, some MPs manoeuvred to allow the Commons to vote on what policy they want the government to follow. Such efforts have so far been unsuccessful, but it has raised the question of whether parliament could take control.

Possible options include a vote to instruct the UK government to rescind article 50 (although this would also require a vote to repeal the EU Withdrawal Act 2018). This would, if also agreed to by the EU, take a no deal Brexit off the table. Government could also be instructed to ask for an extension of article 50 while further negotiations are attempted. Parliament could try to define what agreement the UK should pursue, such as specifying that the UK should work towards membership of the EEA or EFTA. Finally, parliament could decide that the issue should be put to the British people, through a second referendum. This would also involve parliament setting out what options would be on the ballot paper.

This has raised a number of constitutional and political questions, not least whether any outcome in which parliament instructs government to pursue a specific course would mean the government had lost the confidence of the House of Commons and therefore a general election should be called. However, because of the Fixed Term Parliament Act 2011, calling a general election is no longer a matter of the government losing a single vote of no confidence. Furthermore, should a general election be called and result in a hung parliament, then questions would again be raised as to whether there existed any clear majority for a specific way forward.

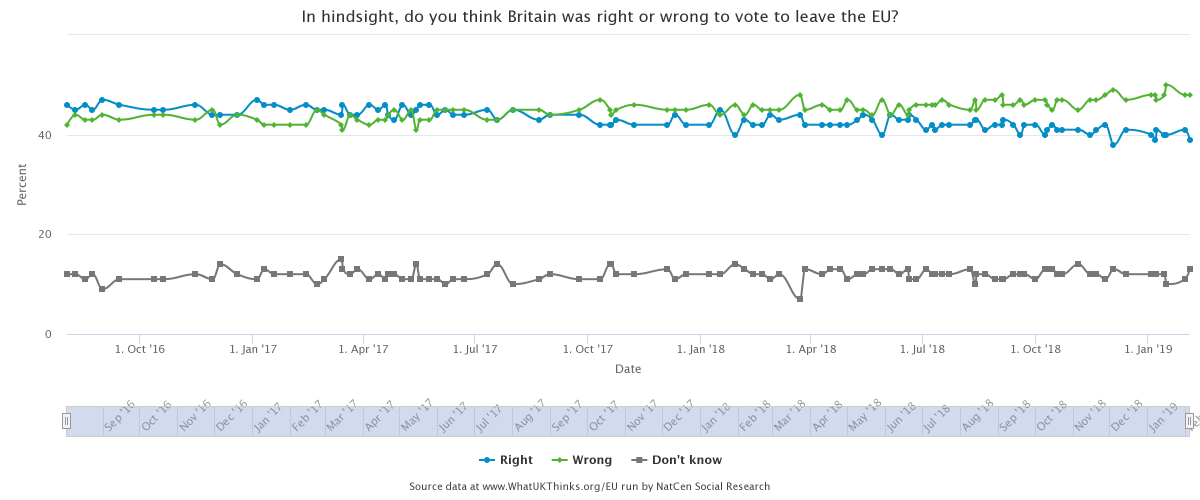

There is also the question of how the British people themselves feel about developments within parliament. As shown in Figure 1 below, divisions within the House of Commons reflect a divided nation.[10] Reversing the Leave vote or failing to stop Britain’s exit could be as damaging for popular perceptions of MPs as the 2009 parliamentary expenses scandal.[11] In such a fluid and uncertain situation one thing appears certain: a large proportion of British voters will be left bitter and angry at the outcome of the negotiations.

Figure 1 | Aggregate poll analysis (2016-2019) on the question: In hindsight, do you think Britain was right or wrong to vote to leave the EU?

Source: NatCen, What the UK Thinks.

Overall, parliament’s role in the UK-EU withdrawal negotiations has highlighted how Brexit has consumed, confounded and humiliated Britain’s political class. It has thrown parliament’s place in Britain’s uncodified constitutional system into a state of flux. In some respects parliament has gained from Brexit thanks to the opportunities to assert itself vis-à-vis the executive. How sustainable this is, or whether it will extend into parliament’s wider prerogatives, remains an open question.

The Conservative government has struggled to control Brexit in part due to the lack of a majority, deep divisions across all parties and a repeated inability by ministers to develop a coherent strategy for moving forward. This does not necessarily apply to most other areas of political activity such as health or taxes, where executive dominance looks set to continue. Brexit could therefore be something of an anomaly in the long-term pattern of executive dominance in UK politics.

Nevertheless, whatever happens next, Brexit will continue to dominate both British politics and the proceedings of the Westminster parliament. Brexit, it should be remembered, is not a single event or process, but a multilevel series of processes unfolding at different rates and over different timeframes.

The deal emphatically rejected by the House of Commons on 15 January 2019 only covered Britain’s withdrawal. The politics of approving, scrutinising and instructing a way forward, such as reversing Brexit or amending and accepting the Withdrawal Agreement, let alone scrutinising and agreeing to a new UK-EU relationship, promise to be just as interminable, difficult and divisive.

* Tim Oliver is Senior Lecturer for the Institute for Diplomacy and International Governance, Loughborough University London.

This article is the first in a number of IAI Commentaries published in the framework of the Mercator European Dialogue project, run by the German Marshall Fund (GMF), the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) and the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB).

[1] Supreme Court, Judgment in the Article 50 ‘Brexit’ Appeal, 24 January 2017, https://www.supremecourt.uk/news/article-50-brexit-appeal.html.

[2] Institute for Government, “Parliament’s ‘Meaningful Vote’ on Brexit”, in Explainers, updated 5 February 2019, https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/node/6519.

[3] “EU Vote: Where the Cabinet and Other MPs Stand”, in BBC News, 22 June 2016, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-35616946.

[4] UK Parliament, “Government Loses ‘Meaningful Vote’ in the Commons”, in Commons News, 16 January 2019, https://www.parliament.uk/business/news/2019/parliamentary-news-2019/meaningful-vote-on-brexit-resumes-in-the-commons.

[5] “Brexit Studies Details ‘Will Be Published’”, in BBC News, 2 November 2017, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-41849030.

[6] Jessica Elgot, Rajeev Syal and Heather Stewart, “Full Brexit Legal Advice To Be Published After Government Loses Vote”, in The Guardian, 4 December 2018, https://gu.com/p/a5xyf.

[7] House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee, “European Union (Withdrawal) Bill. 3rd Report of Session 2017–19”, in HL Papers, No. 22 (28 September 2017), p. 2, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/lddelreg/22/22.pdf.

[8] House of Commons, “Leaving the EU”, in Hansard (21 January 2019), Vol. 653, Col. 28, http://bit.ly/2HJsYTX.

[9] “Theresa May Suffers Three Brexit Defeats in Commons”, in BBC News, 5 December 2018, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-46446694.

[10] See results from 108 polls, conducted from 1 August 2016 to 4 February 2019. Available in What the UK Thinks, https://whatukthinks.org/eu/questions/in-highsight-do-you-think-britain-was-right-or-wrong-to-vote-to-leave-the-eu.

[11] “MPs Expenses Scandal: A Timeline”, in The Telegraph, 4 November 2009, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/mps-expenses/6499657/MPs-expenses-scandal-a-timeline.html.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, February 2019, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

19|10

Topic

Tag

Related content

-

Video14/06/2019

Taking Back Control?

leggi tutto -

Ricerca21/05/2015

Open European Dialogue (former Mercator European Dialogue)

leggi tutto