Back from the Brink: An Israeli-Palestinian Proposal for Jerusalem

As I write these words, violence has once again descended upon Jerusalem. In early May 2021, peaceful Palestinian protesters were violently attacked by Israeli police and hundreds were wounded when the police stormed the holy esplanade (Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif) in the Old City.

In a tragically familiar turn of events, from Jerusalem violence gradually spread all over historic Palestine, leading to a serious 11-day escalation.

Reflecting on these past developments, I recall how in 2001–2003, during the bloodiest days of the second Intifada, a group of Israelis and Palestinians that I have the privilege of being part of, refused to lose hope. Together we agreed on the Geneva Initiative, a comprehensive model for a two-state framework in Israel/Palestine.

Likewise, today we reject the notion that the Holy City is destined to remain a place of eternal conflict. Hereafter we suggest a new blueprint for an equitable sharing of the city that we hope can provide inspiration for policymakers and residents alike.

Open Jerusalem

According to the Geneva Initiative, Jerusalem would be physically split into two independent capitals. Special arrangements inside the city and border crossing stations around it, would ensure that access to the Old City and its holy sites would be open to all, with sovereignty divided between the independent states of Israel and Palestine.[1]

The urban and demographic reality in Jerusalem and its environs has undergone substantial changes in the nearly two decades since 2003, creating greater unequal interdependence between the Israeli and the Palestinian sides. This brought Israeli and Palestinian experts of the Geneva Initiative (including the author) to present an alternative to the hard border model inside Jerusalem.[2]

Our new proposal for an “Open Jerusalem” examines the practicability of two open capitals set within the framework of two states. The proposal is not exhaustive. Nor does it shy from confronting the more challenging topics, such as security. It does, however, acknowledge the complexity of the issue and outlines areas that necessitate further study.

The proposal seeks to prepare the ground for future talks. Since much has changed all over Occupied Palestinian Territory (OpT), some of the proposals contained in the “Open Jerusalem” framework may be relevant for peace building beyond the city as well.

Guiding principles

Three core principles – that have been broadly lacking in previous rounds of diplomatic talks – guide our Open Jerusalem proposal:

First, Open Jerusalem will begin with the well-defined end goal of two sovereign states with two open capitals in Jerusalem, mapping out gradual steps toward achieving this objective in what may be termed a “role back” strategy.

Second, the proposal champions a local, city-led perspective for Jerusalem rather than the exclusive top-down and state-led perspective that directed former final status talks. State agencies deem that most of the important political problems can be solved once national sovereignty is established. City dwellers, however, are clearly more concerned with what happens in their place of residence and livelihood. Trust building at the local city level is achieved through everyday urban encounters, whereas at the state level it is limited to high level officials.

Third, “Open Jerusalem” looks at the city as a living urban entity beyond its unquestionable historical, religious or national-symbolic status as well as beyond its symbolic-national status. Urban wellbeing, openness, inclusivity and sustainability do not imply making the city less secure.

Hard-border problems

Four core problems call for a reconsideration of the hard border concept between the two capitals. Firstly, there is the practical problem of a border crossing next to the Old City gates due to the sheer volume of vehicle and pedestrian traffic between the sides.

Sites sacred to Christians, Muslims and Jews are located across the Old City. It would be difficult if not impossible to check the large number of people every weekend and on holydays, nor is it possible to locate checkpoints next to Jaffa and Damascus Gates without severely damaging commercial centres adjacent to each that currently establish a living link between the two sides.

Second, Israel’s expansion to the east of the pre-1967 war line, with the expressed purpose of preventing a division of the city’s Palestinian and Israeli areas, impedes the ability to build a hard border. This and the separation wall that Israel built in 2003 divide East Jerusalem businesses from their hinterland in the West Bank. East Jerusalemites residents, have consequently turned westwards, heightening the mutual – yet unequal – dependency of the city’s Jewish and Palestinian sections.

Almost half of the East Jerusalem labour force work in the West side and earn their wage there.[3] More than ever East Jerusalem Palestinians visit West Jerusalem shopping centres, use its public transportation and study in its universities and colleges. In addition, new transportation infrastructure has been constructed including highways and a tramline connecting East and West Jerusalem, as well as Israeli settlements built beyond the 1967 line.

Third, there is growing awareness among both Israeli and Palestinian Jerusalemites about the mutual benefits of keeping the city open and prevent turning al-Quds and Yerushalayim into near lifeless dead-end border cities, or worst still the epicentre of new bouts of intra-ethnic and confessional violence.[4] Thriving cities require diversity, exchange and openness.

Forth, fiscally dividing Jerusalem along ethnic lines would necessitate huge and costly infrastructure works to reverse decades of heavy Israeli investment.

The Open Jerusalem regime

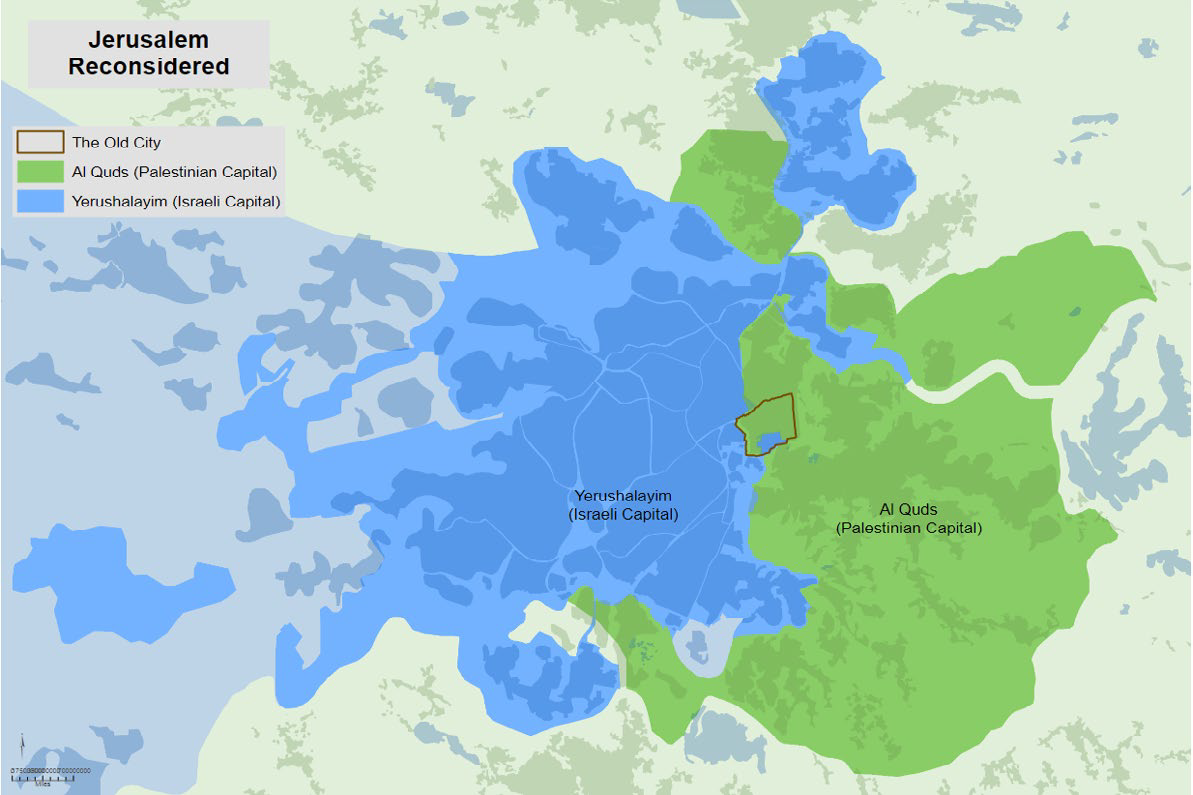

With regards to municipal boundaries, our open Jerusalem proposal envisions the prospective Israeli Yerushalayim municipality to include Jewish neighbourhoods and settlements, while the and Palestinian al-Quds municipality would include all Arab neighbourhoods (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 | Open Jerusalem proposal, 2021

Source: Geneva Initiative, Jerusalem Reconsidered, cit., p. 33.

Areas that exist in close proximity of the municipal boundaries that would delineate the open border within the city must be treated sensitively. No party should enjoy absolute authority to develop its respective side without consulting the other.

With regards to the issue of institutional authority, we recommended that the states of Israel and Palestine give maximum power to the two separate municipalities. As reflected in the Geneva Initiative, the two sides should form a Jerusalem Coordination and Development Committee (JCDC) to oversee cooperation.

During its creation and based on international experience, the following issues should be addressed by the committee: structure and responsibilities related to the desire for coordination; dispute settlement mechanisms with an agreed role for third party monitoring and evaluation of implementation and the criteria for appointing delegates to the joint committee.

The two states should for instance agree on visa policy matters, security issues and the economy. At the municipal level, systematic cooperation should be established on areas encompassing emergency and health services, transportation, higher education, tourism, environmental protection, religious sites and festivals, archaeological sites, energy and water.

Moving to the economy, we suggest a model that enables the free movement of goods, people and capital between the two cities and ideally the two states. The three relevant options include signing a bilateral economic agreement including free trade and the use of the two national currencies; creating a special economic zone in order to attract international investment or adopting a model similar to that which exists among Gulf Cooperation Council states. This latter option can include elements from the previous ones.

The separation wall fosters slum conditions in East Jerusalem and an asymmetric interdependency between it and West Jerusalem. Removing this physical separation, with all that it entails in both symbolic and practical terms, and creating an independent al-Quds while maintaining freedom of movement between it and Yerushalayim would benefit both peoples and capitals. Freed from Israeli control over sectors such as tourism, basic services, planning and housing, Palestinian residents would see substantial improvements in their quality of life and could further benefit the development of the open city.

With regards to infrastructure and basic services, attempts to disconnect and separate the electricity, water and sewage systems all at once would be technically problematic and harm the everyday life of residents. Instead, Open Jerusalem suggests first separating the management of these lines and then gradually working towards physical separation. Special arrangements should be found for cross-border transportation and environmental systems of shared interest.

Turning to the sensitive issues of policing and security, each state will assume responsibility for the maintenance of law and order in its capital. A joint policing command team with special legal status can synchronise cross-sovereignty operations. The subject requires further study and there is value in drawing best practices from international cases (e.g. the EU experience) on command hierarchy, locational jurisdiction and security arrangements as they relate to legal arrangements.

A series of advanced technological solutions such as biometric cameras and smart identification procedures aimed at diminishing the physical imposition of hefty checkpoints infrastructure could also be deployed. Advanced technology, privacy and security cooperation could help to mitigate the security risks by potential spoilers on both sides.

In the context of an open city it would be more desirable to have a series of easy crossing points dotted along the agreed-upon location. Jerusalemites will have maximum and easy movement and will not require a visa for access. Smart city technologies can also contribute to the monitoring of people within each side which can serve as an additional security element. Further study is needed to identify the right solution to security and legal challenges introduced by those technologies.

Finally, given the undisputed religious and cultural significance of Jerusalem, religious rights and cultural heritage must also figure prominently in any agreed resolution on the final status of Jerusalem. Within the parameters of a two-state framework, cultural heritage properties within Israeli territory would fall under Israeli jurisdiction and vice versa. The reciprocity principle of free access maintenance and respect for each sides’ narrative should guide this process.

Further recommendations include expanding the Jerusalem World Heritage site to include the open area, establishing a joint cultural heritage council with UNESCO participation, returning all artefacts previously excavated in the territory of the other side to its original place and enhancing a cultural heritage management system.

Preparing the ground

This Open Jerusalem proposal can only work in the context of a broader political environment, very different from that which exists today. It requires a peace process based on a clear framework and parameters for action.

The EU and the US have a special responsibility to push both sides and societies towards this objective. If and when room is created for diplomacy, Open Jerusalem will be worth considering.

To help prepare the ground for new and creative arrangements we propose a number of concrete recommendations below.

• For Israel, the PLO and international mediators: Negotiations over Jerusalem should not be postponed until other components of the final status agreement have been completed as agreed in Oslo Accords. Moreover, in order to build trust, the sides should implement areas that have been agreed upon while discussions on other issues continue.

• For Israel and international mediators: There should be a freeze on the building of Israeli settlements in occupied East Jerusalem, on house demolitions and forcible evictions and a prohibition on land confiscation in East Jerusalem.

• For the international community: Establish an international fund to help East Jerusalem overcome its lack of significant investment in infrastructure and services. The fund will receive applications from East Jerusalem NGOs and work with them directly.

• The international community should put pressure on Israel to let East Jerusalemites vote in Palestinian Legislative Elections as the case was in 2006, and in accordance with the Oslo Accords. Pressure on the Palestinian Authority to announce a new date for the elections should similarly be applied.

• Israel should let the Arab Studies Society reopen Orient House, the cultural and identity centre of East Jerusalem that Israel closed in 2002, and return its confiscated library collection. In addition, Israel should let Palestinian Jerusalemites select their local representatives to represent community needs to the Israeli municipality, and receive international donations to improve services and infrastructure utilised by Palestinian residents.

Menachem Klein is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Political Science at Bar-Ilan University (Israel) and former advisor to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Shlomo Ben-Ami and Prime Minister Ehud Barak.

[1] The Geneva Initiative full text, annexes and maps are available in the Geneva Initiative website: The Accord, https://geneva-accord.org/?p=543. See also Klein Menachem, A Possible Peace Between Palestine and Israel. An Insider’s Account of the Geneva Initiative, New York, Columbia University Press, 2007.

[2] Geneva Initiative, Jerusalem Reconsidered. Two Capitals, One Undivided City, March 2021, https://geneva-accord.org/?p=1741.

[3] Marik Shtern, “Towards Ethno-National Peripheralisation? Economic Dependency Amidst Political Resistance in Palestinian East Jerusalem”, in Urban Studies, Vol. 56, No. 6 (May 2019), p. 1129-1149.

[4] See 2018 public opinion survey: Dan Miodownik and Noam Brenner, One City Two Realities: Jerusalem 2018 Public Opinion Survey, Survey Report of the project “Building Visions for the Future of Jerusalem: A Bottom Up Approach”, April 2018, p. 20-21, https://jerusalemvisions.huji.ac.il/node/281613.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, June 2021, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

21|29