LNG and the Uncharted Future of US-EU Energy Relations

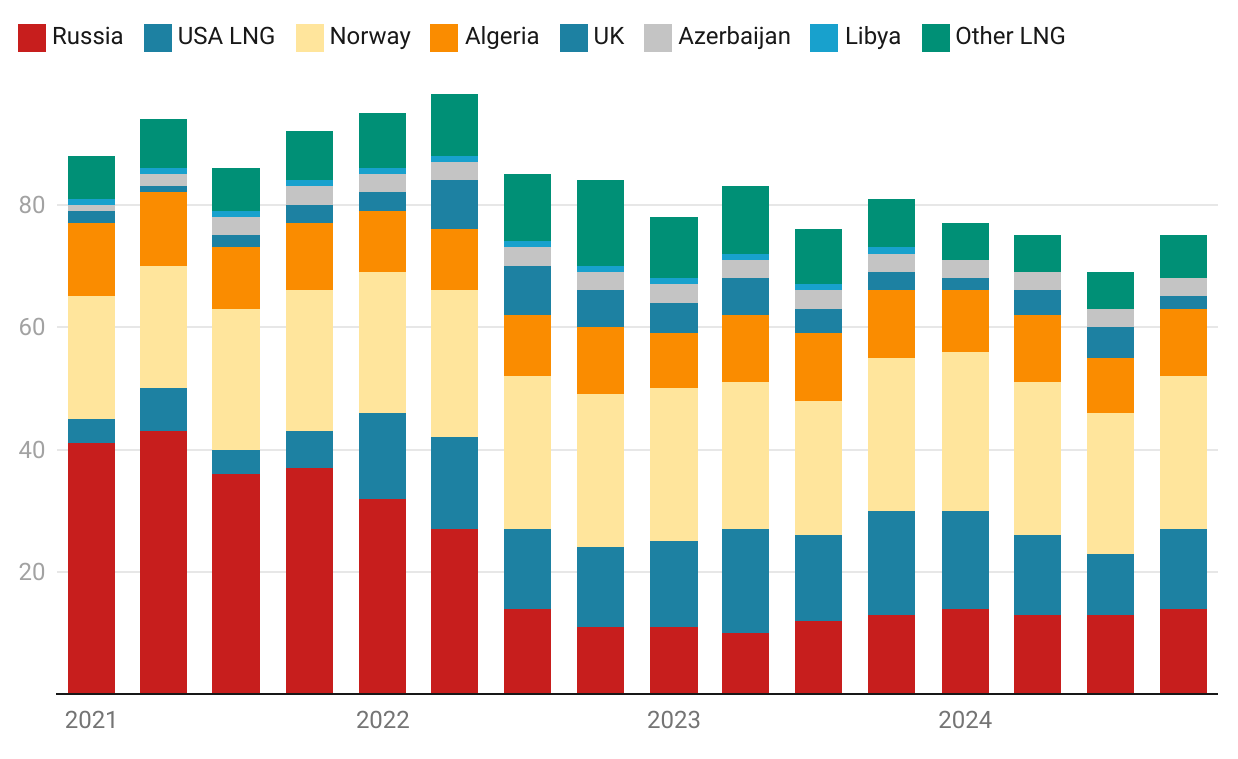

The European Union and the United States are historical allies with shared political values and highly integrated economies united by the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship. This transatlantic link was strengthened in 2022 by joint efforts in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In this effort, the energy dimension has been a crucial component. As Europeans were facing lower Russian-piped gas imports, the European Union had to redesign its supply portfolio in order to avoid disruptions, looking to increase its imports from a variety of gas-exporting countries, namely Norway, Algeria, Azerbaijan and the US itself. Precisely, US liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes were pivotal in providing security of supply to their European allies (Figure 1). In March 2022, the two sides formed a Task Force on Energy Security aimed at weaning Europe off overdependence on Russian supplies and accelerating supply diversification.[1]

The energy crisis has indeed provided a new momentum in Europe for LNG imports, which are now the baseload – a role once held by Russian piped gas. 37 per cent of EU primary gas supply are sourced by LNG imports. Within this trend, the transatlantic energy interdependence was substantially enhanced: in 2024, US LNG amounted to around 45 per cent of EU LNG imports and the EU was the destination of 43 per cent of US LNG exports.

Such deepening energy trade was supported at the highest political level. Pledges to ensure at least 15 bcm of US LNG to Europe in 2022 were made by the Biden administration, while the European Commission’s goal was to ensure stable demand for additional US LNG of around 50 bcm/y until at least 2030.

As Donald Trump returned to the White House, this interdependence is at the crossroads, not only due to growing political disagreements and diverging regulatory approaches, but also market uncertainties.

Figure 1 | EU quarterly gas imports by source, 2021Q1-2024Q4, bcm

Source: Author’s elaboration on Bruegel Natural gas import database [accessed on March 2025].

The political dimension

The goal of the new Trump administration is to unleash US energy.[2] This strategy is expected to ensure cheap energy to US consumers and expand the country’s LNG export capacity. The advent of US LNG a decade ago has substantially changed the global gas markets and clearly holds a strategic value for the US.[3] US energy sources are instrumental in pursuing ‘energy dominance’ as they would reduce reliance on foreign countries while enhancing ties with others.[4] Furthermore, in Donald Trump’s effort to reduce the US’s trade deficit with key partners, LNG also has economic and trade value. Unsurprisingly, President Trump has been very vocal in supporting higher LNG trade with Europe to reduce the massive trade deficit with the EU (in 2024, amounting to 235.6 billion US dollars).[5] Already back in November 2024, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen suggested this option in the attempt to deter Trump from imposing tariffs on Europe.[6] This approach had already been pursued in 2018 with the deal between then-President Trump and von der Leyen’s predecessor, Jean-Claude Junker.[7]

However, such a course of action is now problematic for multiple reasons. Firstly, in these first Trump’s months in office, the US has threatened and later imposed tariffs on the EU countries, along others. Thus, it is clear that buying more LNG would not solve the problem of tariffs. The willingness to buy more LNG did not prevent the imposition of tariffs in the first place. Indeed, the LNG trade value would not be enough to fundamentally address the issue, as its value depends on both volume and price. Higher volumes may not be enough as the global LNG market is expected to be well supplied by the end of this decade, resulting in lower prices. Furthermore, LNG can only partially address the trade deficit since according to the US Census Bureau, US LNG exports to the EU amounted to around 13 billion US dollars, equal to only around 5.4 per cent of the total trade deficit.[8] It has also to be noted that the European Commission has no legal authority to sign contracts, which are under the control of (international) market-driven companies that can sell LNG also outside Europe. Lastly, the energy crisis highlighted the importance of diversified supplies. From a supply security standpoint, it would be unwise for European countries to simply switch overdependence from one supplier to another – especially given growing political disagreements.

Deregulation vs regulatory power: The case of methane emissions

In Washington DC, deregulation is considered the best option to achieve energy dominance and reduce energy costs. Indeed, Trump has accused climate regulations as one of the main barriers to the growth of US energy resources, as they would be an additional cost for producers and consumers. Therefore, the current administration has increasingly undertaken important decisions to roll climate targets and regulations back, especially on methane emissions[9] (a greenhouse gas with a warming potential more than 80 times stronger than CO2 over a twenty-year period). For example, on 12 March, the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched the biggest deregulatory action in US history, unveiling 31 deregulatory actions to reverse measures set by the Biden administration, reconsidering regulations on the methane emissions from the oil and gas industry (OOOO b/c).[10]

Such deregulation efforts, however, clash with Brussels’ traditional regulatory power, which has increasingly been dedicated to methane emissions in the past years. The EU adopted its Methane Regulation that entered into force in August 2024. The regulation sets important standards for domestic producers, but more importantly imports – given its dependency. The Regulation implementation will occur in steps over the 2025-2030 period. By January 2027, exporters will need to demonstrate equivalent monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) measures to those of EU operators. From 2028, they will need to report on the methane intensity and by 2030 demonstrate that imports to the EU are below the maximum methane intensity values (to be set later by the Commission).

In short, US deregulation on methane emissions in the gas value chain may ultimately undermine the commercialisation of US LNG in the European market. Something similar already occurred back in 2020, when French Engie decided to halt negotiations with the US company NextDecade over an LNG supply (signed with certain safeguards in May 2022) because of alleged pressure from the French government over environmental concerns – particularly methane emissions. Given these commercial risks, large US companies are eager to remain committed to methane emissions reductions because of developments in key importing countries not only in Europe, but also in Asia.[11] Indeed, Japan and South Korea have launched the “Coalition for LNG Emission Abatement toward Net-Zero” (CLEAN) to reduce methane emissions in the LNG value chain.[12]

This trend suggests that deregulation does not necessarily entail the demise of emissions reduction efforts (especially for large companies), but shifts the burden on operators and consumers. It implies different attitudes towards regulation and reforms within the fragmented US gas supply chain, with medium and smaller operators advocating for more reforms while large producers have both interests and means to comply with the existing regulations.[13] In the absence of a strong US regulatory regime, the fragmented US gas supply chain may be ill-positioned to meet EU requirements – compared to other gas exporting countries.[14]

Lastly, methane (de)regulation may become a hot topic in US-EU negotiations as the Trump administration is increasingly targeting potential EU regulations that supposedly penalise US products in Europe although methane regulations have not yet been identified as such.[15]

Market arguments between short- and long-term

This final consideration leads to the last dimension that will shape the future of the US-EU energy relations: the market. Despite the political convergence in 2022, it was the market, in the form of price signal, the main driver for the increase of the transatlantic energy trade in the aftermath of Russia’s war on Ukraine. Indeed, US LNG is largely sold by private-owned companies on a ‘free on board’ basis that guarantees destination flexibility. The record-high gas prices in Europe encouraged operators to reroute cargoes across the Atlantic.

By looking at supply and demand in the short term, there are a few reasons to expect energy trade between the two sides to deepen further. On the supply side, the US is expected to increase its LNG export capacity by 17 per cent in 2025 according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) forecast, with the expected commencement of two LNG facilities. On the demand side, the EU may rely more on LNG imports as it faces the demise of the Ukrainian transit (around 14 bcm in 2024) and higher gas supplies needed to refill its storage capacities ahead of the winter season.

However, focusing only on short-term convergence between the two sides of the Atlantic may be fallacious, as market uncertainties related to Europe’s future gas demand pose long-term challenges. In Europe, the ‘golden age of gas’ (recorded more than a decade ago by the International Energy Agency) appears to be fading away as a result of the combination of Russia’s war on Ukraine, the rise of renewables as well as economic troubles and headwinds. By contrast, other regions, notably Asia, are expected to experience a rise in gas demand due to environmental reasons (due to coal-to-gas switching), demographic and economic growth as well as the expansion of data centres, becoming far more central for future US LNG exports. Furthermore, in the case of a ceasefire in Ukraine, the temptation of accepting (limited) volumes from Russia, aimed at bringing energy prices down in the name of industrial competitiveness, may erode some European demand for higher US LNG imports in the medium and longer term as well as reducing the price signal. All these considerations have contributed to fewer new long-term contracts for US LNG signed by European operators compared to Asian buyers.

Furthermore, considerations over the future supply-demand equation in the US are needed. Trump calls for higher production (through the ‘Drill, baby, drill’ mantra) and the US will need to ramp up its production to sustain its economic, industrial and digital ambitions and ensure export volumes.[16] To increase their output, however, companies and operators require adequate price levels to make investment decisions,[17] highlighting again the limits of Trump’s influence over private companies.[18]

As Europe has expanded its reliance on LNG markets, it will need to navigate challenging waters with its historical partner and top LNG supplier: the US. Growing political confrontation and market developments could intentionally (or not) narrow future opportunities.[19] Nonetheless, US LNG remains critical in the future global energy trade, providing growing and flexible supplies. Thus, it is in the US’ and the EU’s interests to collaborate on both energy security (through some new contracts, where possible) and addressing the environmental footprint – especially with regard to methane emissions (through diplomacy). At the same time, the two sides should avoid harmful politicisation of LNG trade – especially in the context of tariff negotiations – acknowledging its limited contribution to reducing the US-EU trade deficit.

Pier Paolo Raimondi is a Researcher in the Energy, Climate and Resources programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) and a PhD Candidate at the Catholic University of Milan.

[1] US and EU, Joint Statement between the European Commission and the United States on European Energy Security, 25 March 2022, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_22_2041.

[2] White House, Unleashing American Energy. Executive Order, 20 January 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/unleashing-american-energy.

[3] Ben Cahill, “U.S. LNG Export Boom: Defining National Interests”, in CSIS Commentaries, 11 January 2024, https://www.csis.org/node/108869.

[4] White House, Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Establishes the National Energy Dominance Council, 14 February 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/02/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-establishes-the-national-energy-dominance-council.

[5] United States Trade Representative (USTR) website: European Union, accessed on March 2025, https://ustr.gov/countries-regions/europe-middle-east/europe/european-union.

[6] Barbara Moens, Gabriel Gavin and Clea Caulcutt, “EU’s Opening Bid to Avoid Trump’s Tariffs: We Could Buy More American Gas”, in Politico, 8 November 2024, https://www.politico.eu/?p=5686239.

[7] David Smith and Dominic Rushe, “Trump and EU Officials Agree to Work toward ‘Zero Tariff’ Deal”, in The Guardian, 25 July 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/p/93gmm.

[8] Anne-Sophie Corbeau, “Bridging the US-EU Trade Gap with US LNG Is More Complex than It Sounds”, in Energy Explained CGEP Blog, 20 February 2025, https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/?p=22190.

[9] The US Senate voted to scrap the methane waste fee on oil and gas industry included in the Inflation Reduction Act invoking Congressional Review Act process. “Congress Kills Biden Era Methane Fee on Oil, Gas Producers”, in Reuters, 27 February 2025, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/congress-kills-biden-era-methane-fee-oil-gas-producers-2025-02-27.

[10] EPA, EPA Launches Biggest Deregulatory Action in U.S. History, 12 March 2025, https://www.epa.gov/node/295224.

[11] Valierie Volcovici, “US LNG Exporters Stick with Methane Measures despite EPA Rollbacks”, in Reuters, 20 March 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-lng-exporters-stick-with-methane-measures-despite-epa-rollbacks-2025-03-20.

[12] JERA, Launch of the Methane Emission Reduction Initiative (CLEAN) by KOGAS and JERA, 18 July 2023, https://www.jera.co.jp/en/news/information/20230718_1565.

[13] Kevin Book et al., “Will Trump Mend or End Federal Methane Rules?”, in CEESA White Papers, January 2025, https://www.ceesa.utexas.edu/s/Jan-2025-White-Paper_FINAL_V3.pdf.

[14] Pier Paolo Raimondi, “A New EU-MENA Energy and Climate Partnership: The Case for Cleaner Molecules”, in Yusuf Can and Maša Ocvirk (eds), The Future of Euro-MENA Relations, Washington, Wilson Center, October 2024, p. 46-57, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/node/123988.

[15] USTR, 2025 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, 31 March 2025, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/Press/Reports/2025NTE.pdf.

[16] Mrinalika Roy, “US Natgas Producers Chase AI-driven Surge in Power Demand to Weather Low Prices”, in Reuters, 21 November 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-natgas-producers-chase-ai-driven-surge-power-demand-weather-low-prices-2024-11-21.

[17] Amanda Chu, “Trump ‘Chaos’ Threatens US Oil Output, Say Shale Executives”, in Financial Times, 26 March 2025, https://www.ft.com/content/192de972-4661-40ce-a649-6a5476ae5c18.

[18] Rebecca F. Elliott, “Oil Companies Embrace Trump, but Not ‘Drill, Baby, Drill’”, in The New York Times, 27 January 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/27/business/energy-environment/oil-trump-drill-baby-drill.html.

[19] Stefano Porciello, “Eurogas Chief: New EU Gas Contracts Face Uncertainty, and Trump Tariffs Won’t Help”, in Euractiv, 4 April 2025, https://www.euractiv.com/?p=2235334.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, April 2025, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

25|20