Illegal Trafficking of Plastic Waste: The Italy–Malaysia Connection

Illegal Trafficking of Plastic Waste: The Italy–Malaysia Connection

Elisa Murgese*

China’s 2018 import ban on mixed “recyclable” plastic waste revealed deep-rooted problems in the global recycling system and uncovered the wasteful and harmful nature of the recycling trade. Repercussions have been global. In April 2019, Greenpeace East Asia took a closer look at the top plastic waste importers and exporters globally.[1]

This data details the 21 top exporters and 21 top importers of plastic waste from January 2016 to November 2018, measuring the breadth of the plastics crisis and the global industry’s response to import bans. Two core trends emerged from China’s ban and the Greenpeace analysis.

In the first instance, we traced how the majority of plastic waste originally destined for China was redirected to less-regulated countries, especially in Southeast Asia, but also other areas that lack adequate restrictions to stop outsized imports, or any real capacity to manage the waste. Secondly, following the Chinese ban, global plastic exports dropped by about half from 2016 to 2018. As a result, former exporters now also struggle with a surplus of waste, unprocessed or processed inadequately.

Ultimately, the report highlights that the top three importing countries between January 2018 and November 2018 were Malaysia (15.7 per cent of total imports), Thailand (8.1 per cent) and Vietnam (7.6 per cent). With regards to exports, the US came in first place, while Italy was ranked 11th out of the 21 top exporters, accounting for 2.25 per cent of total plastic waste exports.[2]

The above data demonstrates Malaysia’s crucial role in the global plastic waste business. However, according to confidential documents obtained by Greenpeace Italy, the Italy–Kuala Lumpur route seems to be at the centre of a major illegal traffic of plastic waste.

In February 2020, a new investigation by Greenpeace Italy’s Investigative Unit revealed that in the first nine months of 2019, nearly half of Italian plastic waste sent to Malaysia was illegally shipped to plants devoid of an “approved permit”,[3] and therefore operating with no regards for the environment and human health, in clear violation of national and EU laws.

Greenpeace’s analysis focused on mixed plastic waste – i.e. containers, wrappings, industrial films and plastic residues of all kinds – widely used in our daily life, but difficult to recycle.[4] Until two years ago, this waste was mainly shipped to China, which absorbed up to 42 per cent of Italian plastic waste exported outside the EU. These exports are carried out by private companies and intermediaries, not the government or local authorities.

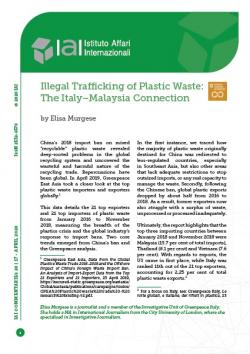

Following the Chinese import ban in 2018, Malaysia ranked as the first importer of Italian plastic waste according to Eurostat data and from January to September 2019 was the second importer among non-EU countries (Table 1). During the first 9 months of 2019, almost 7,000 tons of plastic waste was exported to Malaysia between direct and indirect shipments, for a value of about 1.5 million euro.[5]

Table 1 | Top destinations of Italian plastic waste exports, January–September 2019

Source: Elisa Murgese, “L’Italia sta inondando di plastica la Malesia: un traffico illegale da più di mille tonnellate”,

in L’Espresso, 10 February 2020, https://espresso.repubblica.it/inchieste/2020/02/10/news/plastica-italia-malesia-traffico-illegale-1.344113.

To identify non-EU recipient countries, Greenpeace analysed Eurostat data, where the export of plastic materials is reported (with customs code 3915). Greenpeace then obtained confidential documents that allowed to focus exclusively on direct shipments of Italian plastic waste to Malaysia, excluding – unlike Eurostat data – quantities of Italian plastic destined to Malaysia but shipped throughout the intermediation of companies from third countries (indirect shipments) or secondary raw materials (shipment unaccompanied by annex VII).

In other words, while Eurostat analysed the entire export of plastic material with customs code 3915 for the first nine months of 2019 (equal to 6,955 tons), Greenpeace only took into consideration the direct shipments of Italian plastic waste to Malaysia (equal to 2,880 tons between September and December 2019).

The Investigative Unit has ascertained – throughout the scrutiny of confidential documents – that out of these 2,880 tons, more than 1,300 (equal to 46 per cent) have been shipped illegally because destined to Malaysian companies with no authorisation to import and recycle foreign waste. During the first nine months of 2019, 43 out of 65 direct shipments were involved in these illegal forms of export.

Verification of this data was made possible through cross-examination: Greenpeace Italy confronted the list of 68 Malaysian companies which – between January and September 2019 – were authorised to import and process foreign plastic waste, with confidential documents regarding Italian shipments. The comparison showed how almost half of Italian plastic waste sent directly to Malaysia was destined for non-authorised plants.

If such findings were confirmed by the competent authorities, serious criminal charges would be expected. As noted by Paola Ficco, an Italian environmental legal expert and lawyer, charges could involve organised waste trade, illegal waste trafficking and transnational conspiracy.[6]

Greenpeace Italy’s investigation also casts significant doubts on the legality of shipments in 2018. Back in July 2018, Malaysia had preventively closed many recycling plants due to safety and regulatory concerns. As a precautionary measure, between August and December 2018, all licenses for the industries in the sector were withdrawn pending a re-assessment.[7]

Following this suspension, one would have expected a drop in export flows towards the country. Instead, Greenpeace’s investigation highlights how 3,500 tons of plastic waste were sent from Italy to Malaysia between August and December 2018, for a total value of 660,000 euro. This is not a negligible sum, considering Italy had already sent 9,400 tons of plastic waste to Malaysia between January and July 2018 (when the import market was still open).

The international trafficking of plastic waste exposed by Greenpeace is in contrast with relevant European legislation. Every delivery of plastic waste from Europe towards non-EU countries must follow very strict procedures. These are contained in Regulation (EC) 1013/2006 which specifies the obligation for European countries to send their plastic waste outside EU borders only and exclusively for recycling or reuse.[8]

Moreover, destination plants must have technical and environmental standards equal to those of the EU and must operate “in an environmentally sound manner”, namely “in accordance with human health and environmental protection standards that are broadly equivalent to standards established in Community legislation”.[9]

Greenpeace has proof this legislation is not being respected. In addition to the scrutiny of export documents, our Investigative Unit travelled to Malaysia between July and August 2019, to check on the conditions of the plants where Italian plastic waste is being shipped.

Footage, taken by Greenpeace’s hidden cameras, revealed Malaysian entrepreneurs willing to import and handle Italian waste, both contaminated plastic and urban garbage, although they do not appear on the list of authorised companies produced by the Malaysian government, and therefore lack the necessary permits.

This illegal trafficking is having negative effects on the daily life of Malaysian citizens, who are forced to live in an increasingly polluted territory. As shown by previous Greenpeace research, plastic recycling factories operating illegally are creating serious problems to the environment and public health.[10] Comparing data from 2018 and 2019, in a single year there has been an increase of up to 30 per cent in respiratory diseases.

In August 2019, Greenpeace analysed samples of water, soil and plastic fragments from different illegal dumping sites for foreign plastic waste (including Italian) in Malaysia. The results are alarming: high concentrations of heavy metals (such as cadmium and lead) and the presence of persistent organic pollutants, such as brominated flame retardants and phthalates (known endocrine disruptors used in the production of certain plastic materials) were detected in samples of plastic fragments in the soil.

Hazardous chemicals were also found in ash samples, mixed with plastics, collected in one of the illegal dumping sites where hydrocarbons were detected, including benzo(a)pyrene, a known human carcinogen.

The situation documented by Greenpeace in Malaysia is unacceptable for a progressive EU country like Italy. Rapid intervention by competent Italian authorities is needed to stop these illegal practices. Furthermore, the investigation highlights, once again, one of the many criticalities regarding the management of plastic material at the end of the product lifecycle. If we consider that only 9 per cent of total plastics produced since the 1950s have been effectively recycled, it is not surprising to stumble upon cases such as the Malaysian one.[11]

Recycling on a global scale, promoted by companies and governments as the main response for plastic pollution, cannot alone be considered an effective solution. Recent estimates have noted how the production of plastics is expected to quadruple by 2050.

Preventing plastic pollution and clamping down on the illegal trade of plastic waste requires concerted action by governments, companies and consumers. On the one hand, there is a need to limit the production of often unnecessary and difficult to recycle single-use plastic, which alone today accounts for 40 per cent of global plastics production.

On the other, we need immediate action to stop illegal trafficking of plastic waste from rich to underdeveloped countries. Strong coordination among governments is required to halt this phenomenon.

The global south cannot continue being used as an illegal dumping site by northern countries, which are fond of describing themselves as “civilised”. Such practices are akin to cleaning one’s house by sweeping dust under the carpet. Not only are such practices illegal and detrimental to the health and environment of developing states, but will ultimately come back to haunt all states who share this planet.

Enhancing international oversight and cooperation of the global plastic waste business is essential to raise awareness and prevent such activities from taking place. While limiting the production of plastic – and particularly single-use plastic – is necessary, this must go hand in hand with increased activism by governments, civil society and consumers, which alone can put in place the needed accountability to curtail these phenomena. This is the only way to preserve our planet, preventing it from being transformed into a planet of plastic waste and pollutants.

* Elisa Murgese is a journalist and a member of the Investigative Unit of Greenpeace Italy. She holds a MA in International Journalism from the City University of London, where she specialised in Investigative Journalism.

[1] Greenpeace East Asia, Data from the Global Plastics Waste Trade 2016-2018 and the Offshore Impact of China’s Foreign Waste Import Ban. An Analysis of Import-Export Data from the Top 21 Exporters and 21 Importers, 23 April 2019, https://secured-static.greenpeace.org/eastasia/Global/eastasia/publications/campaigns/toxics/GPEA%20Plastic%20waste%20trade%20-%20research%20briefing-v2.pdf.

[2] For a focus on Italy, see: Greenpeace Italy, Le rotte globali, e italiane, dei rifiuti in plastica, 23 April 2019, https://www.greenpeace.org/italy/rapporto/5246.

[3] Malaysia’s National Solid Waste Management Department, Plastic Waste Import Policy for Customs Code 3915, 7 September 2016, https://jpspn.kpkt.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/145.

[4] For “plastic waste” we intend all waste catalogued HS Code 3915: “Waste, parings and scrap, of plastics”. See World Customs Organization, HS Nomenclature 2017 Edition, Section VII, Chapter 39 (0739-2017E), 2017, http://www.wcoomd.org/-/media/wco/public/global/pdf/topics/nomenclature/instruments-and-tools/hs-nomeclature-2017/2017/0739_2017e.pdf.

[5] This refers to the value of goods at reporting countries’ customs (FOB value, free on board, times the value of export/shipping).

[6] Elisa Murgese, “L’Italia sta inondando di plastica la Malesia…”, cit.

[7] “Permanent Ban on Import of Plastic Waste”, in Daily Express, 28 October 2018, http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/news.cfm?NewsID=128339.

[8] Regulation (EC) No 1013/2006 of 14 June 2006 on Shipments of Waste, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2006/1013/2018-01-01.

[9] Ibid., p. 48.

[10] Greenpeace Italy, Che fine fanno i rifiuti in plastica che esportiamo?, 19 September 2019, https://www.greenpeace.org/italy/storia/6120.

[11] Roland Geyer, Jenna R. Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law, “Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made”, in Science Advances, Vol. 3. No. 7, e1700782 (19 July 2017), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700782.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, April 2020, 5 p. -

In:

-

Issue

20|16