The Trouble with Italy's Development Cooperation

The Trouble with Italy’s Development Cooperation

Bernardo Venturi*

Development cooperation is recognised as an essential component of foreign policy. In Italy, the sector has long suffered from a lack of transparency, accountability and effectiveness. A recent reform has improved some dimensions, but Rome still has a long way to go to bring development assistance more in tune with international standards and Italian interests.

In 2014, a comprehensive reform of the Italian development cooperation system (Law 125/2014) changed many aspects, from governance to stakeholder participation, from transparency to the role of the private sector. The reform also established an Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS), bringing Italy in tune with its European partners, many of which had long since established similar specialised agencies.[1] Reflecting efforts to accord development cooperation greater role in Italian foreign policy, the reform also changed the name of Italy’s foreign affairs ministry, now named the “Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation” (MAECI).

The reform was launched after more than 20 years of debate and political proposals to change the previous system in place since 1987, which had become obsolete after the end of the Cold War. While the reform was welcomed by Italian partners and many civil society organisations, problems persist particularly regarding funding and the prioritisation of development cooperation over other domains.

Italy’s present coalition government clearly does not consider development cooperation a priority in its own right. Instead, it has undertaken a number of initiatives that may well undermine the improvements of the 2014 reform. The government’s fixation on migration, rather limited technical and political experience and, more broadly, its embrace of opportunistic transactionalism in foreign policy are preventing a consistent approach to development cooperation.

In the past, Italy’s international development cooperation suffered from a lack of prioritisation and strategic goals. For instance, between 1987 and 1994, Italy financed as many as 117 countries failing to define geographic or thematic priorities.[2] Besides, in the early 1990s, Italian development cooperation was tarnished by a number of serious political scandals which almost paralysed the government’s action, also contributing to a stalemate in efforts to reform Italian development cooperation.

These Italian shortcomings were also a by-product of the country’s low foreign policy profile during the Cold War. Development cooperation lacked a geographic orientation or direct link with Italian interests, and most decisions on aid were oriented by the Vatican or leftist and Catholic NGOs.[3]

The 2014 reform was therefore badly needed. It was a key step towards the creation of a more coherent and efficient system in line with the standards of the EU and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

One of the main innovations of the 2014 reform is the establishment of AICS. The agency, which has been in operation since January 2016, has enhanced transparency and the efficiency of project management and oversight, among other things.[4] It has ensured transparency in calls and tenders, improved monitoring and evaluation and expanded the involvement of the private sector.

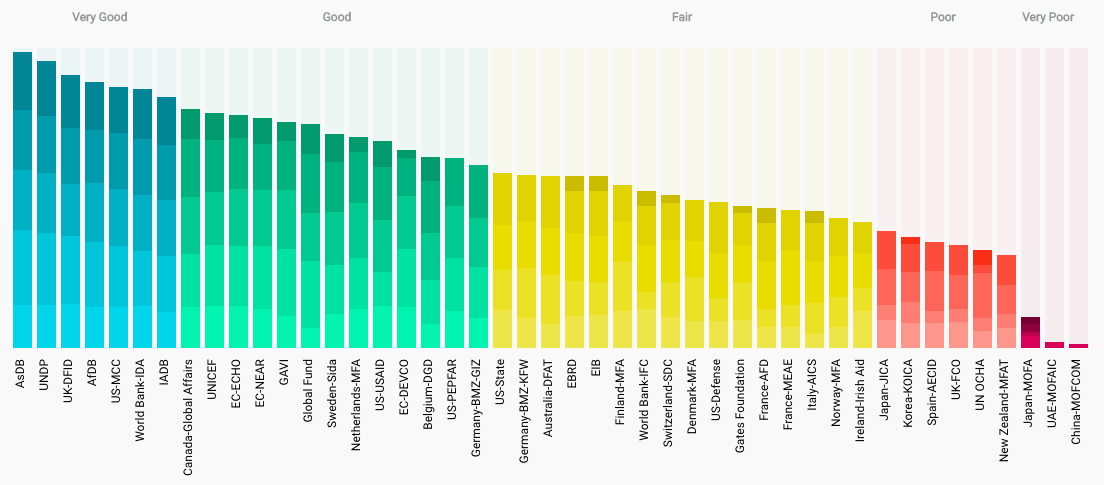

AICS has, inter alia, joined the International Aid Transparency Initiative, and has begun publishing data on its activities. Thanks to this, AICS was classified as “fair” by the Aid Transparency Index 2018, a position that still places Italy behind a majority of other donors (see Figure 1),[5] but does represent an improvement compared to the past.

Figure 1 | The 2018 Aid Transparency Index

Source: Publish What You Fund, Aid Transparency Index 2018, cit.

In terms of budgetary allocations, from 1990 to 2017 Italy’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget varied from a minimum of 0.11 per cent of gross national income (GNI) (1997) to a maximum of 0.34 per cent (1992). Significantly, it increased from 0.14 to 0.30 per cent from 2012 to 2017, reaching a total amount of 5,858 million US dollars (5,203 million euro) in 2017.[6]

In September 2018, an update to Italy’s Economic and financial document (DEF), which spells out the government’s budgetary forecasts for the following three years, placed Italian ODA at 0.33 per cent of GNI in 2019, predicting further increases to 0.36 per cent in 2020 and finally to 0.40 per cent by 2021.[7]

However, in 2018, Italy’s ODA decreased to 0.24 per cent of GNI from the 0.30 of the previous year.[8] Moreover, according to estimates by Openpolis and Oxfam, in 2019 funds for development aid will fall to 5,077 million euro, decreasing to 4,654 million euro in 2020 and 4,702 million in 2021. Based on a forecast of 1 per cent GDP growth, such funding would be equal to 0.29 per cent of Italy’s GNI in 2019 and 0.26 per cent in 2020 and 2021.[9]

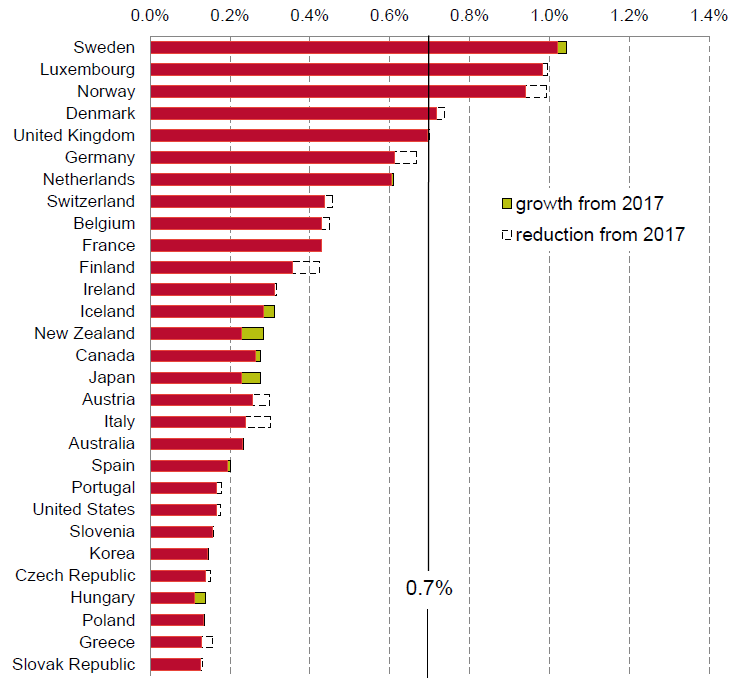

Notwithstanding such contradictory forecasts, Emanuela Del Re, Italy’s Deputy Minister in charge of development cooperation, has recently outlined yet another estimate, promising that Italian ODA will reach 0.30 per cent of GNI by 2020.[10] Independently from which estimate one believes, it is clear that Italian ODA in 2018 is modest compared to the other OECD donors (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Initial analysis of the preliminary ODA data for 2018 provided by OECD-DAC

Source: Development Initiatives, Preliminary ODA Data 2018 – Total Falls for Second Consecutive Year, 10 April 2019, http://devinit.org/?p=18235.

Yet, official budget totals relating to ODA are also misleading. This is due to a significant change introduced in 1988 that allows donor states to include the costs associated with hosting refugees in their territories in ODA totals.

The number of migrants landing on Italian shores decreased by 80 per cent in 2018, but the 2018 decrease in Italy’s ODA budget outlined in the figure above is only partially due to decreases in the cost of hosting refugees. OECD data shows that such costs remained high: 1,125 million US dollars in 2018 (23 per cent of Italian ODA) compared with 1,804 million in 2017 (30 per cent). Excluding refugee costs, Italian ODA therefore actually decreased by 12.3 per cent in 2018.[11]

Geographically, Africa maintains a predominant role, especially for funding channeled by AICS, followed by the Middle East. Italy has allocated approximately 36.5 per cent of its aid though AICS to sub Saharan Africa in 2016–2017. When it comes to funds not financed by AICS, other more developed countries also figure prominently. For instance, Argentina (debt relief) and Turkey (humanitarian aid related to migration flows). A further 20.5 per cent of Italy’s ODA is allocated for initiatives in Europe.[12]

In addition to limited economic resources and their questionable allocation, recent political trends are also threatening to cast a dark shadow on Italy’s ODA outlook. On 4 April, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte nominated Luca Maestripieri as AICS’s new director, a decision that is reflective of broader trends within the government and its approach to development cooperation.

Firstly, the nomination of Maestripieri came more than one year since the resignation of the previous director, Laura Frigenti. That such a long period was needed to nominate a new director shows the difficulties the government has encountered in defining its plans for development cooperation. Indeed, domestic issues and migration are dominating the Italian political landscape. As a result, development cooperation has tended to be marginalised.

Secondly, Frigenti had a truly international profile: she had previously worked with the World Bank for almost 20 years, taking on increasingly important roles. Instead, Luca Maestripieri is a diplomat. This broke the equilibrium between the MAECI, which plays more of a political role, and AICS, which has more technical and operational responsibilities. It seems that the government has preferred to maintain direct control over AICS instead of preserving a healthy relationship between the two institutions.

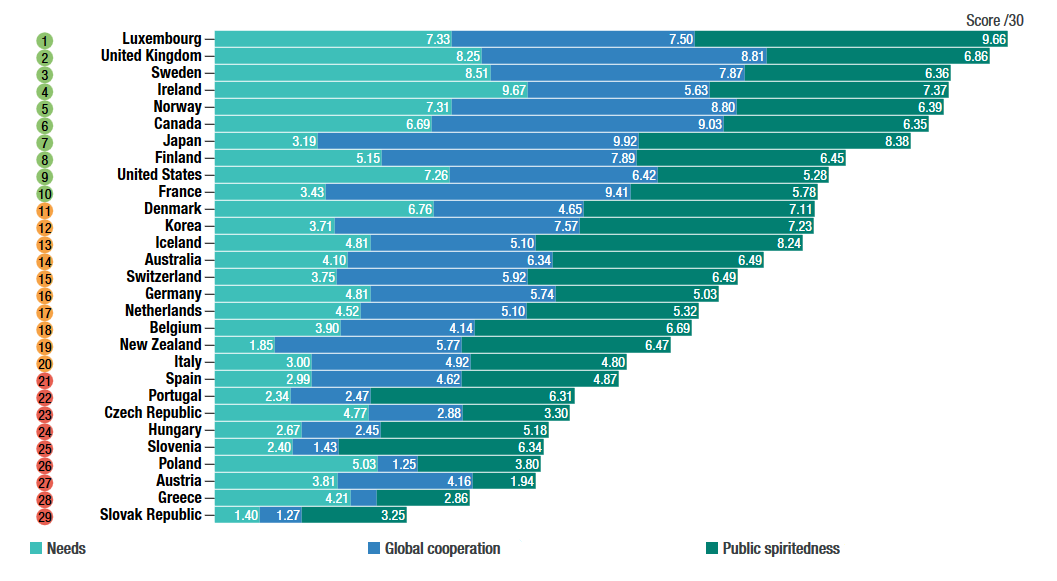

In such a scenario, one can predict a growing politicisation of development aid and the further weakening of Italy’s embrace of a principled approach that targets countries on the basis of actual needs or emergencies as opposed to geopolitical interests or other considerations (see Figure 3). This dynamic may reduce both the efficiency and impact of Italy’s ODA efforts as well as undermine the improvements implemented thanks to the 2014 reform.

Figure 3 | Principled Aid Index: data disaggregated by principle

Source: Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Principled Aid Index, March 2019 https://www.odi.org/node/33892.

At the same time, there is a risk that resurgent nationalist tendencies and the government’s persistent emphasis on security risks associated with migration, continue to divert resources and attention toward migration management and control, depriving other sectors of badly needed funding and support.

Few would debate that Italian development cooperation has witnessed improvements compared to the past. Yet, recent trends are putting these gains at risk.

Italian politicians and civil society should redouble their efforts to accord a greater priority and organisation to Italy’s foreign aid and development cooperation, avoiding a harmful politicisation of the issue while raising awareness as to the importance of a strong and principled aid programme. For a “middle power” like Italy, development cooperation, if managed efficiently and strategically, can complement Italian policies in other sectors, allowing Rome to maximise its influence and thereby strengthen its ability to advance broader foreign policy priorities.

* Bernardo Venturi is Senior Fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] Luca De Fraia, “Italy Overhauls its Development Cooperation System”, in CONCORD Blog, 9 September 2014, https://wp.me/p76mJt-jK.

[2] Fabio Fossati, Economia e politica estera in Italia. L’evoluzione negli anni novanta, Milano, Franco Angeli, 1999, p. 147.

[3] Fabio Fossati, “Italian Foreign Policy After the Cold War”, in EFPU Working Papers, No. 2008/3 (June 2008), p. 5, http://www.lse.ac.uk/internationalRelations/centresandunits/EFPU/EFPUpdfs/EFPUworkingpaper2008-3.pdf.

[4] AICS website: AICS Field Offices, https://www.aics.gov.it/?page_id=10158.

[5] Publish What You Fund, Aid Transparency Index 2018, June 2018, http://www.publishwhatyoufund.org/the-index/2018.

[6] OECD Data: Net ODA, https://data.oecd.org/oda/net-oda.htm.

[7] Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, Nota di aggiornamento del Documento di economia e finanza 2018, 27 September 2018, p. 42, http://www.dt.mef.gov.it/modules/documenti_it/analisi_progammazione/documenti_programmatici/def_2018/NADEF_2018.pdf.

[8] Italian Ministry of Economy and Finance, Documento di economia e finanza 2019. Programma di stabilità dell’Italia, 9 April 2019, p. 170, http://www.dt.tesoro.it/modules/documenti_it/analisi_progammazione/documenti_programmatici/def_2019/01_-_PdS_2019.pdf.

[9] Openpolis and Oxfam, Italy’s Official Development Assistance: Back to the Past, February 2019, p. 5-6, https://www.openpolis.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Cooperazione-Italia_EN.pdf.

[10] Paolo Biondi, “Emanuela del Re: entro il 2020 lo 0,30% del Pil per la cooperazione internazionale”, in Vita, 18 May 2019, http://www.vita.it/it/article/2019/05/18/emanuela-del-re-entro-il-2020-lo-030-del-pil-per-la-cooperazione-inter/151625.

[11] OECD, Development Aid Drops in 2018, Especially to Neediest Countries, 10 April 2019, p. 8, http://www.oecd.org/development/development-aid-drops-in-2018-especially-to-neediest-countries.htm.

[12] Openpolis, “4. Impegno per lo sviluppo, la differenza tra il dire e il fare”, in Cooperazione Italia, ritorno al passato, January 2019, https://www.openpolis.it/esercizi/impegno-per-lo-sviluppo-la-differenza-tra-il-dire-e-il-fare.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, June 2019, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

19|37