The Weaponisation of Finance and the Risk of Global Economic Fragmentation

The decision by the US and Europe to disconnect select Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) and to freeze Russia’s foreign reserves might have significant, long-term effects on the international monetary system. While transformations in this system have historically been slow to materialise, the range and scope of the recently deployed sanctions will likely catalyse a global push to diversify from the US dollar-centric global financial system.

Whether the US and European countries, as well as their allies, will strengthen or reduce financial sanctions against Russia in the future, the “weaponisation” of finance against a G20 country like Russia sets an historical precedent that will amplify concerns that one day any country could be disconnected from western-dominated financial infrastructure.[1] In the latest G20 meeting of finance ministers, Chinese Minister of Finance Liu Kun strongly criticised the “politicisation” of the global economy, warning that such moves may undermine international economic cooperation.[2]

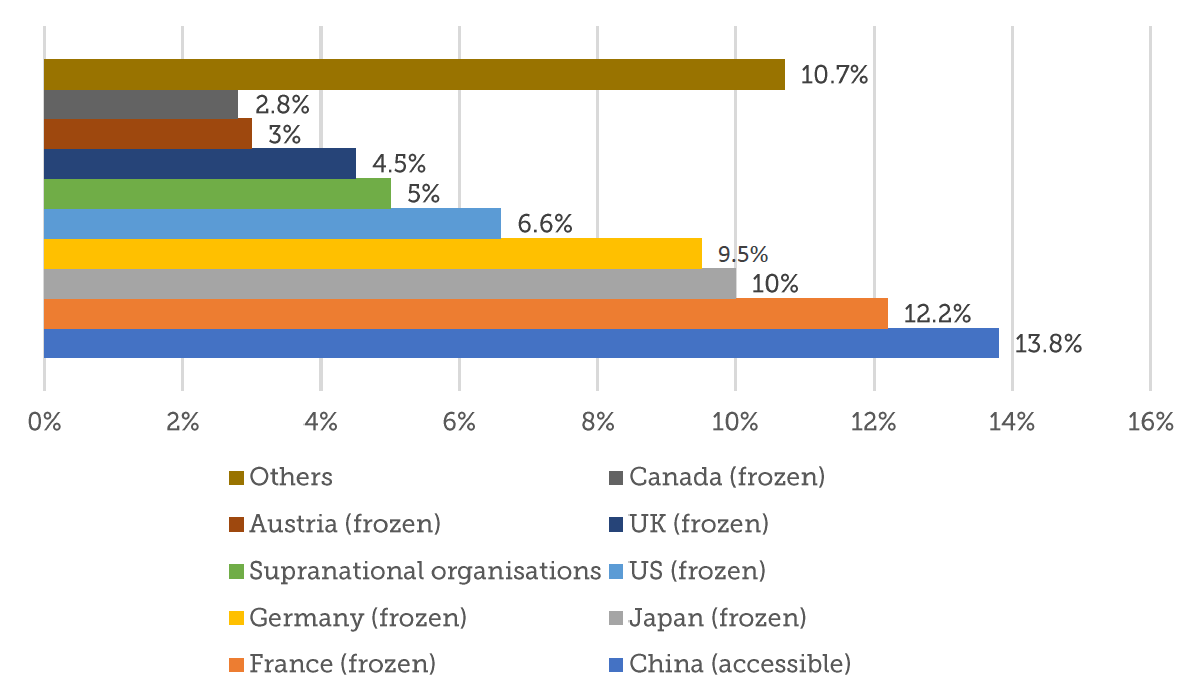

Figure 1 | Location of Bank of Russia foreign exchange reserves and gold assets in June 2021

Source: author’s elaboration from Bank of Russia Foreign Exchange and Gold Asset Management Report, No. 1/2022, http://cbr.ru/Collection/Collection/File/39685/2022-01_res_en.pdf.

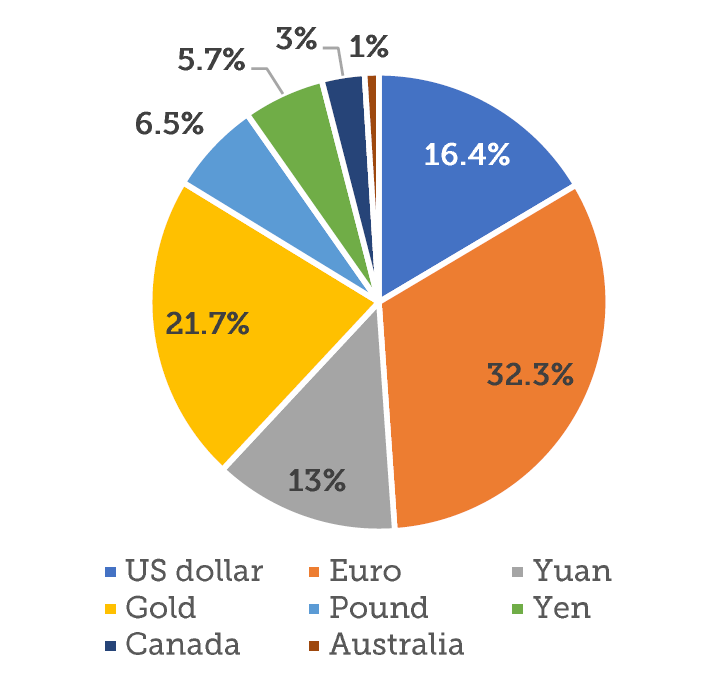

Figure 2 | Composition of Bank of Russia’s assets in foreign currency and gold as of June 2021

Source: author’s elaboration from Bank of Russia Foreign Exchange and Gold Asset Management Report, No. 1/2022, cit.

While it is true that no other contender could challenge the existing US-dominated dollar system in the short-to-medium term, the US and its allies should strategically reflect upon the long-term implications if their leadership in the global monetary system is eroded.

Debates on the US dollar’s international dominance are nothing new. Even before the war in Ukraine, it was widely acknowledged that the current global monetary regime provided the US with an extremely efficient bulwark to leverage and enforce its foreign policy internationally. As the global economy relies on the US dollar as the primary medium for cross-border transactions and foreign reserves, the US derives significant economic and national security benefits from its central role in the global financial system.[3]

Over the past twenty years, several countries have been attempting to make their currency an attractive alternative to the US dollar. China has implemented significant efforts to globalise its national currency as, compared to its economic power, the yuan significantly underperforms as an international currency, making Beijing highly depended and vulnerable to the US dollar.[4] Also the European Union, one of the US’s closest allies, has set the goal of increasing the internationalisation of the euro as a key dimension of its ambitions for a strategic autonomy.[5]

Countries have moreover tried to reduce their dependency on the US-controlled global payment infrastructure. For example, China, Russia and India have repeatedly expressed their interest to jointly explore an independent alternative to SWIFT[6] while the EU launched (a rather unsuccessful) EU-Iran payment vehicle INSTEX in 2019 to get around US sanctions re-imposed on Tehran by the Trump administration.

Attempts to significantly erode the US dollar’s dominance have failed thus far, yet there are – small but still relevant – signals of potential trends of fragmentation which could be accelerated by the war in Ukraine. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), for example, has already reported that some countries are renegotiating the currency used to settle their trade agreements in light of the sanctions applied to Russia.

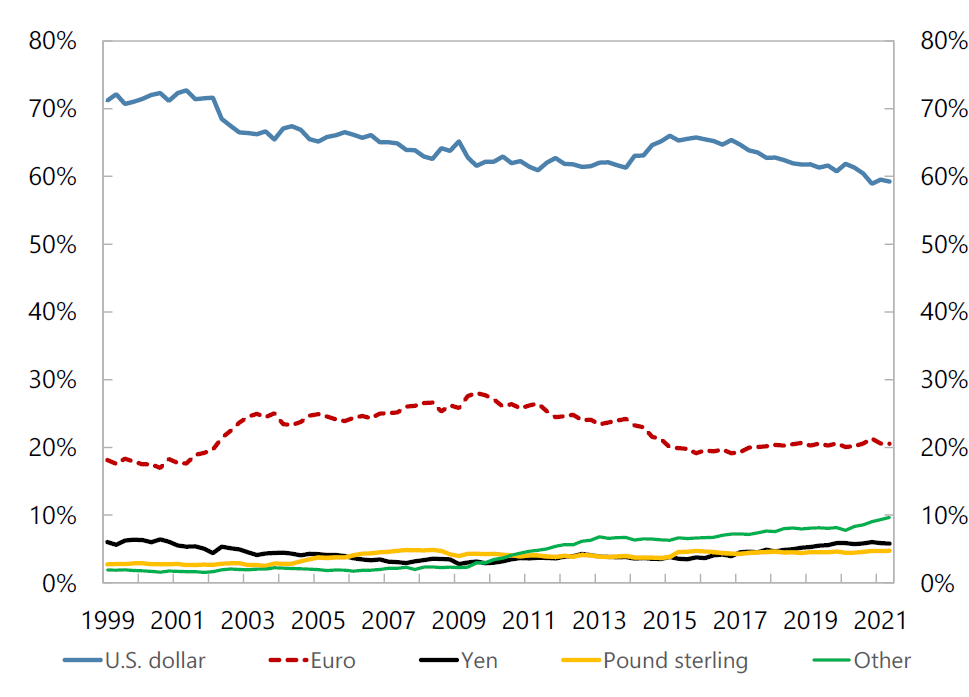

Indeed, foreign reserves in US dollars decreased globally from around 70 per cent at the beginning of the 2000s to 59 per cent in the third quarter of 2021 (Figure 3). According to a recent IMF study, a quarter of this shift was allocated to the yuan while three quarters into the currencies of smaller countries.[7] Thus, central banks have been implementing a portfolio diversification strategy driven by market forces. In this context, the recent weaponisation of the US dollar could accelerate this ongoing diversification process, a trend that may be further incentivised by a “de-risking management” strategy.

Figure 3 | Currency composition of global foreign exchange reserves 1999–2021 (in percent)

Source: Serkan Arslanalp, Barry J. Eichengreen and Chima Simpson-Bell, “The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance, cit., p. 6.

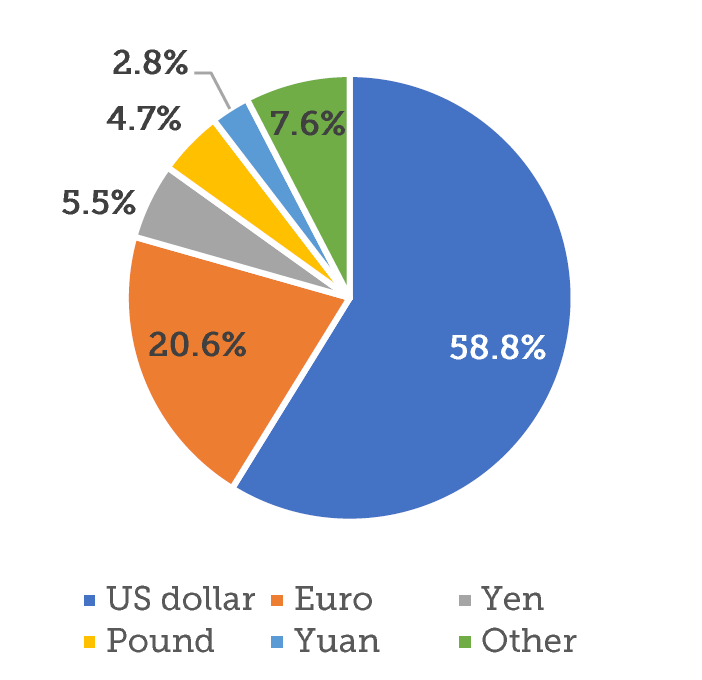

The key question, however, is where this shift could be diverted to, given that a credible alternative to the US dollar is currently lacking. The yuan does not seem to have the underlying characteristics to replace the US dollar. The yuan’s internationalisation is weighted down by policy and institutional factors (like capital account controls or limited convertibility) which cannot be mitigated by geostrategic driven motivations. Furthermore, current trends of growing diversification in the composition of foreign reserves appears to be directed towards other western countries and allies – such as the Canadian dollar, the Australian dollar and South Korean won – states that tend to align with the US foreign policy priorities (Figure 4).

Figure 4 | World allocated reserves by currency for 2021 fourth quarter

Source: author’s elaboration from: IMF Data, Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserve, https://data.imf.org/?sk=E6A5F467-C14B-4AA8-9F6D-5A09EC4E62A4.

Yet, despite their noteworthy operative constraints, alternatives to SWIFT are slowly emerging. China has launched the Cross-Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS) in 2015 while Russia has developed the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS) in 2014. The volume of transactions processed by the CIPS system grew by 83 per cent in 2021 while SPFS doubled the number of processed messages.[8] However, today CIPS and SPFS together process less than 1 per cent of SWIFT’s volume of transactions. SWIFT is reported to carry around 140 trillion US dollars of transactions – of which 40 per cent in US dollars, 37 per cent in euro and 6 per cent in UK pounds.[9]

In the medium term, CIPS could be a more realistic and attractive option as the yuan has a stronger international status than the Russian rouble. Moreover, China could potentially foster CIPS’ adoption through its extensive global trade links. Nevertheless, CIPS is constrained by the low internationalisation of the yuan – which today is used for only 3.2 per cent of global payments.[10] Moreover, the CIPS system is directly linked with SWIFT as it can enable the transmission of information related to a transaction through either CIPS or SWIFT channels. Currently, CIPS and SWIFT are cooperating more than competing.[11]

What seems more plausible in the medium term is that new alternatives, like CIPS, could consolidate regionally and along trade links, ultimately leading to the establishment of different multilateral payment systems which cooperate and compete among each other.

Inertia and frictions are key forces that tend to consolidate the hegemony of the US dollar but, in this context of a growing politicisation of money, the process of financial digitalisation can be a crucial force of change in pushing diversification in both the composition of foreign reserves and cross-border payment systems. In the former area, with the advent of automated and electronic trading platforms which significantly lower transaction costs, central banks have gained a much easier and cheaper access to foreign currencies, incentivising reserve diversification.

Furthermore, the possible introduction of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) around the world has the potential to lower the costs of cross-border transactions.[12] In a future scenario in which several national CBDCs are developed, bilateral and multilateral CBDC-arrangements can promote the establishment of a new payment system network based on multi-CBDCs arrangements in which exchange risks are drastically reduced and nodes are more independent from the US dollar.

However, to enable this potential, there is the need of some degree of cooperation on shared standards and protocols which design interoperability between CBDC systems. As China is the frontrunner in the global race for CBDC’s issuance, Beijing is levering its first-mover advantage to globally influence the development of CBDCs. The People’s Bank of China has already proposed a set of global rules to empower basic interoperability between CBDCs issued by different jurisdictions and has been promoting experiments in cross-border transactions among CBDCs systems.

Global economic power has been shifting over the last forty years, leading to (slight) trends of fragmentation in the international monetary system. While the war in Ukraine might incentivise countries to seek new ways to reduce their vulnerability to the US-led global financial system, the US dollar is likely to maintain its primary role in the global monetary system.

However, the battleground will be in the long-run when digitalisation could empower decentralisation while undermining the unipolarity of the current system. In this scenario, the US risks losing its leadership in the international monetary system if it fails to embrace and shape a new vision for a digitalised (and increasingly politicised) global monetary system. The US cannot however pursue its sole strategic interests when shaping the new system. Washington should coordinate and cooperate with other western nations on equal ground. Otherwise, the US risks fostering further fragmentation.

While still in the early stages of CBDC development,[13] G7 countries could propose and influence widespread preparations for the introduction of a globally interoperable system for CBDCs.[14] The document Public Policy Principles for Retail Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) endorsed by G7 members under the UK Presidency in 2021 should only be the first step of a much more articulated exercise.[15] Otherwise, the risk is to experience a consolidation of non-complementary systems with China paving the ways towards multilateral standards and infrastructure.

Ultimately, the “weaponisation” of finance might have accelerated existing trends of fragmentation and of the US dollar’s erosion in the international system. If ignored and not properly counterbalanced in the long-run, the US risks not only to lose this unique form of financial leverage but also its ability to shape and influence the global financial order.

Nicola Bilotta is Senior Fellow at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] Russia is the first G20 country – and formally a G8 country – to be targeted by this set of sanctions. Previously, similar sanctions were deployed against smaller countries such as Iran or North Korea, which are less integrated in the world economy.

[2] “G20 Members Should Cooperate in Providing Stability for a Volatile World: Chinese Finance Minister”, in Global Times, 21 April 2022, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202204/1259921.shtml.

[3] White House, Executive Order on Ensuring Responsible Development of Digital Assets, 9 March 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/03/09/executive-order-on-ensuring-responsible-development-of-digital-assets.

[4] “Chinese Banks Urged to Switch Away from SWIFT as U.S. Sanctions Loom”, in Reuters, 29 July 2020, https://reut.rs/309S59u.

[5] Fabio Panetta, A Digital Euro for the Digital Era, Introductory statement at the ECON Committee of the European Parliament, Frankfurt am Main, 12 October 2020, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp201012_1~1d14637163.en.html.

[6] Zongyuan Zoe Liu, “Besides China, Putin Has another Potential De-dollarization Partner in Asia”, in CFR Blog, 11 March 2022, https://www.cfr.org/node/240063.

[7] Serkan Arslanalp, Barry J. Eichengreen and Chima Simpson-Bell, “The Stealth Erosion of Dollar Dominance: Active Diversifiers and the Rise of Nontraditional Reserve Currencies”, in IMF Working Papers, No. 22/58 (March 2022), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/03/24/The-Stealth-Erosion-of-Dollar-Dominance-Active-Diversifiers-and-the-Rise-of-Nontraditional-515150.

[8] Maria Shagina, “How Disastrous Would Disconnection from SWIFT Be for Russia?”, in Carnegie Commentaries, 28 April 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/84634.

[9] “The Geopolitics of Money Is Shifting Up a Gear”, in The Economist, 23 October 2021, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2021/10/23/the-geopolitics-of-money-is-shifting-up-a-gear.

[10] Hirsh Chitkara, “Fearing Crypto and China, the US Hesitates to Pull Russia’s SWIFT Access”, in Protocol, 22 February 2022, https://www.protocol.com/policy/russia-swift-sanctions-ukraine.

[11] SWIFT, SWIFT Offers Secure Financial Messaging Services to CIPS, 25 March 2016, https://www.swift.com/de/node/21786.

[12] BIS et al., Central Bank Digital Currencies for Cross-Border Payments. Report to the G20, July 2021, https://www.bis.org/publ/othp38.htm.

[13] The EU has recently launched the investigation phase of a digital euro project while the Biden’s administration released in March an executive order to investigate on the issuance of a digital dollar.

[14] John Beirne et al., “Central Bank Digital Currencies: Governance, Interoperability, and Inclusive Growth”, in Think7 Policy Briefs, 21 March 2022, https://www.think7.org/?p=3031.

[15] G7, Public Policy Principles for Retail Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), 13 October 2021, http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/finance/211014-documents.html.

-

Details

Rome, IAI, April 2022, 6 p. -

In:

-

Issue

22|19