Why Did Italy Fall Out of Love with Europe?

Why Did Italy Fall Out of Love with Europe?

Rosa Balfour and Lorenzo Robustelli*

Public opinion unhinged: Italy and the EU

Since the shock of the 2016 referendum in the United Kingdom on leaving the European Union, a majority of Europeans rediscovered their pro-EU sentiments. Italians did not, however. During the 2010s, Italy swung from being one of the most enthusiastically pro-EU countries in the history of European integration to one of the most sceptical.

Today, it stands out as the only EU country where fewer than half of the citizens say they would vote to stay in the union.[1] While it should not be assumed that such low support for the EU would translate into an eventual decision to leave the union altogether, possibly due to the fact that Italians tend to trust their national institutions even less than the EU,[2] it is a trend that requires urgent attention.

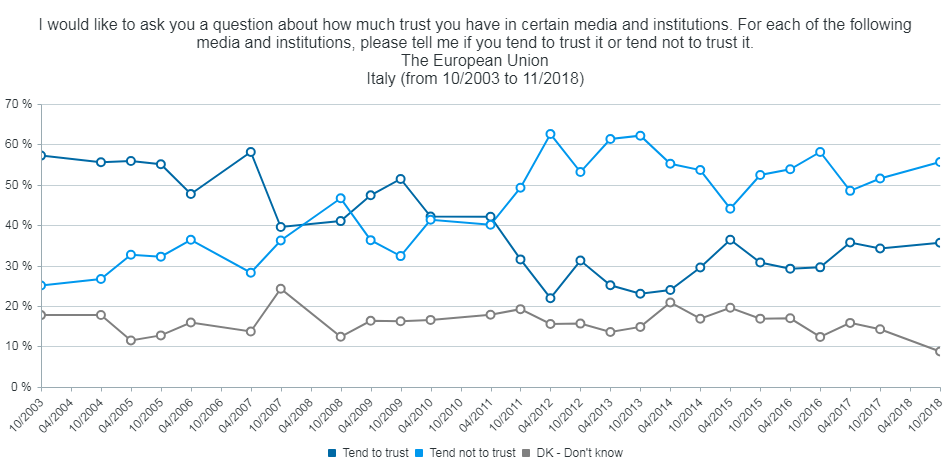

The impact of the 2008 financial crisis on Europe led many Europeans to lose faith in their leaders’ ability to manage the economy. Many recovered some of that trust, but in Italy this has not been the case. In 2008 the percentage of Italians who said they did not trust the EU overtook that of those who said they did (see Figure 1). For the past eight years, far more Italians have said they do not trust the EU than those who do.

Figure 1 | Italians’ trust in the EU

Source: Authors’ elaborations based on Eurobarometer Interactive, http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/index.

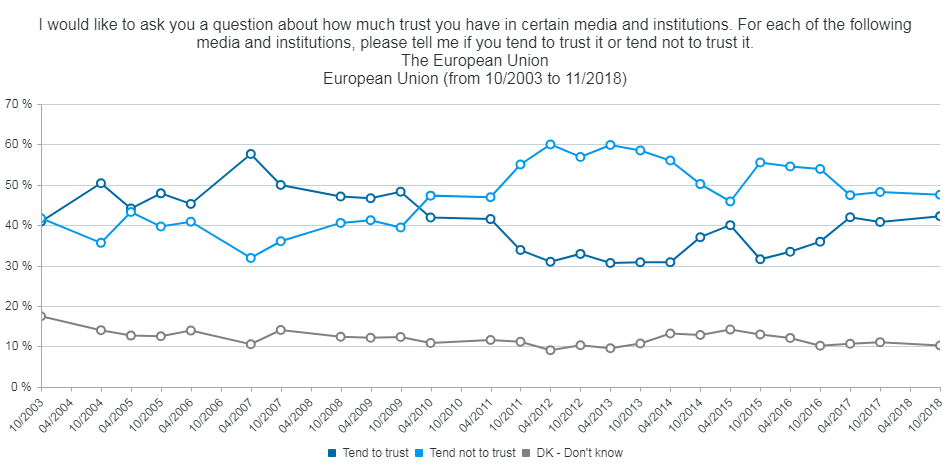

This pattern is not unique. Figure 2 summarises the average historical pattern of trust in the EU across member states. Trust in the EU in many European countries faltered around the time of the Eurozone crisis and other crises of the past decade. Italy was not alone in placing more trust in the EU than in its national institutions and representatives, but only there and in Greece did citizens go through such a dramatic moodswing – and did not come back.[3]

Figure 2 | Europeans’ trust in the EU

Source: Authors’ elaborations based on Eurobarometer Interactive, http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Chart/index.

What happened? This article traces the rise of Euroscepticism in one of the founding members of the EU, seeks explanations for such a tectonic change, and considers the implications for the broader European political landscape.

Euroscepticism in Italy grew alongside the rise of anti-establishment parties since the 1990s. It became mainstream in the 2010s through successive events that caused disenchantment with EU policy. The past decade of crisis over the management of the Eurozone following the 2008 financial crisis, Russia’s resurgence, economic recession, the influx of refugees in 2015-2016 and Brexit, has led to an “evaporation of solidarity”[4] across the EU.

In Italy, the combination of long-term inability to deal with economic and political reform and the immigration challenge was explosive. The country, however, should not be considered an outlier. Its unique history should not overshadow the fact that Italy was in many respects ahead of the curve with regard to the recent changes in European politics. It can serve as a warning and a lesson for the rest of Europe.

The past as a faraway country

For decades, participation in European institutions was of paramount importance for post-war Italy. This helped the country gain international legitimacy after fascism, anchored its democracy to stable regional institutions, and boosted economic growth. From the 1970s, there was a broad cross-party consensus that Italy not only belonged to the Euro-Atlantic structures of the European Economic Community and NATO but was also a committed and active member within them. This embrace continued after the end of the Cold War and the transformation of Italy’s political system, with the country playing a constructive role in successive treaty reforms that created the European Union.

Membership of the EU further bolstered institutional and political reform in Italy. This was widely seen, at least until recently, as necessary for the modernisation of the country. “Ce lo chiede l’Europa” (Europe is asking us to do this) is a widely used slogan to justify attempts to introduce change. Italians are the only citizens in the EU to have accepted a “European tax” in the 1990s to enable it to join the European Stability Mechanism – a necessary step to become part of the Eurozone. Throughout and more than citizens of any other member state, Italians continued to trust the EU far more than their national institutions.

The rise of euroscepticism

Scepticism toward the EU grew as Italian politics took an increasingly anti-establishment turn under Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi when the country’s party system collapsed under the dual pressure of the end of the Cold War and the discovery of massive corruption. The EU was not the primary target of the new parties that emerged from the early 1990s, but gradually it became an easy target to blame for the country’s unsolved troubles.

Berlusconi had issues with EU “interferences” over national matters; held no romanticism about the role of European integration in bringing about peace, democracy, and prosperity; and maintained a preference for personal relationships over international institutions. Thus, his diplomatic efforts to build friendships with Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President George W. Bush were inversely correlated to his limited investment in the EU.

For example, when the EU agreed upon the European Arrest Warrant in 2002 – a significant step in building internal security in the wake of the 9/11 attacks – Berlusconi withheld his consent until the very last moment. Another example of little attention to EU policymaking occurred when the euro was introduced in 1999 and Italy saw a rapid increase in prices. While the president of the European Commission (and former prime minister of Italy), Romano Prodi, pointed out that the government had omitted to create the foreseen committees to monitor price increases,[5] Berlusconi blamed Brussels.

What is significant about this period is less the preferences expressed by Italy on individual policy choices than its transactional approach to EU membership. Until then, all Italian governments had pursued a policy of sitting at the table with the other founding members of the EU no matter what. Participation in the European conclave had been worth more than winning a small battle on a particular issue. Influence within the club was not quantifiable.

By the 2010s this priority seemed to have left the political calculus in favour of domestic politics following two decades of electoral volatility, frequent alternation of governments, including technical ones, and complicated dilemmas with Brussels. Italy had lost prestige during the Berlusconi years, who was at the time seen as a wild card rather than as a sign of the times to come, and the country started to under-invest in the EU.

In 2014 Prime Minister Matteo Renzi proposed his colleague Federica Mogherini for the post of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy rather than for an economic portfolio, which would have better reflected Italy’s core interests at the time. Simultaneously, Renzi opposed the possibility of his predecessor Enrico Letta being put forward as candidate for the presidency of the European Council for domestic political reasons.

The blame game introduced by Berlusconi in the early 2000s was an early example of what soon became standard practice in Italy: blaming Brussels for domestic reasons. Only the governments of Mario Monti and Paolo Gentiloni can be exempted from this.

However, such trends are not unique to Italy. Blaming Brussels and transactionalism in EU-level negotiations have become prominent features in how many member states relate to the EU.

The end of the romance with Brussels

Political opportunism is a likely reason for blaming Brussels. In a political system that remains in flux since its implosion in the 1990s, with political parties atomised, the interests of Italian political actors have focused on seeking immediate gains and electoral benefits. Playing the blame game with the EU was an easy strategy.

From the perspective of Italy, however, there are a number of concrete demands that continued to be unaddressed by the EU and which have fuelled a sense of abandonment and loss of solidarity, most notably the management of migration and of the Eurozone. These dilemmas in the relationship with the EU have persevered regardless of the colour of the government and anti-establishment antics.

At the heart of the Mediterranean and with a weak rule of law, Italy has been a country of transit for migration into the EU and a destination point due to demands of its official and unofficial labour market. The Dublin Regulation on asylum-seeking has worked against the country, forcing it to process the asylum demands of refugees rescued in the Mediterranean with no obligation for other EU countries to share the burden. This bone of contention has been repeatedly raised by successive governments of all stripes since the 1990s but with close to no success. Up until 2011, it proved impossible to include the issue of migration in the central Mediterranean on the agenda of the European Council.[6] The lack of EU solidarity on migration issues is one of the biggest complaints of Italians, one stronger than an alleged rise in anti-immigrant sentiment.[7]

The governance of the Eurozone is the other field where Italy has been involved in a longstanding dispute with Brussels – even Romano Prodi famously called the Eurozone rules “stupid”.[8] The historic public debt and deficit problem that successive governments inherited from the squandering of public finances during the 1980s has been the Sword of Damocles hanging over every governing class since the 1990s, with Brussels demanding reform packages designed for austerity.

This austerity drive proved fatal for Italy’s pro-European elite and rhetoric. The 2011 ousting of the Berlusconi government in favour of an austerity-mandated technical government led by Mario Monti, a former EU commissioner, was initially well-received.[9] But its reforms were not. This paved the way for the talk of a “European coup” against Italian sovereignty and is behind the ensuing electoral volatility of unprecedented dimension in the elections of 2013 and 2018, which saw the spectacular rise of new political forces.

Political dynamics and the power balance within the EU have also not worked in Italy’s favour. European integration has largely been pushed by alliances of countries working together on building common positions. The Franco-German axis has been at the heart of this, but with successive enlargements the EU has seen the emergence of other influential groups, such as the Nordic cooperation, the Visegrad Four, and the Hanseatic League. Mediterranean states have seldom joined forces in a similar way, even if some of their challenges are shared.

The longstanding belief in Italy that the national system is broken has thus been joined by a disillusionment in what the EU can offer to support Italians. All of this has taken place against a backdrop of economic recession, fear of uncontrolled immigration, brain drain, and the emigration of youth, who continue to have little trust in the future. This is what lies behind Italy’s current disenchantment with the EU.

Conclusions

Italy has been depicted as Europe’s basket case, the “sick man” or “soft belly” of Europe – politically fickle and unstable, too large to fail but too difficult to save. This bias has overlooked how, historically, the country, on the frontier of the Cold War and geopolitically exposed at the centre of the Mediterranean, has provided stability and positively influenced European integration.

The story of Italy falling out of love with the EU is uniquely tied to its history and circumstances, yet one should not underestimate the extent to which the country’s ills have actually become Europe’s new normal. Italy has pioneered the rise of eurosceptic politics and parties, which are now challenging the EU status quo across Europe. The transactionalist approach to the EU that Berlusconi embraced is also becoming a mainstream way for governments to interact with Brussels, regardless of their pro- or anti-EU preferences.

Below the surface of political tit-for-tats and blame games, however, lie deeper issues that pertain to the purpose of the EU in providing policy guidance and political solidarity within Europe. These are the governance of Europe’s economy and economic convergence across the continent, and the management of migratory flows. Both issues are central to the European integration project. Large numbers of disaffected citizens in any member state need to be seriously addressed. When such trends of disaffection occur in a large founding member of the EU, it is likely to become a political question for all countries, especially if it affects the union’s decision-making.

For all its responsibilities and faults, Italy’s struggles with the EU’s management of migration and the economy are emblematic of dilemmas that pertain to other countries as well. These have become endemic to the EU as a whole. Addressing them would be in the interest of not just Italy, but the entire Union.

*Rosa Balfour is a senior transatlantic fellow at The German Marshall Fund of the United States. Lorenzo Robustelli is a journalist and director of Eunews in Brussels, having previously worked at Agenzia Apcom (currently TMNews) and Reuters.

This article is the fourth in a number of IAI Commentaries published in the framework of the Mercator European Dialogue project, run by the German Marshall Fund (GMF), the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) and the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB).

[1] Philipp Schulmeister et al., “Closer to the Citizens, Closer to the Ballot”, in European Parliament Eurobarometer Surveys, No. 91.1 (April 2019), p. 21, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/en/be-heard/eurobarometer/closer-to-the-citizens-closer-to-the-ballot. In this poll, 49 per cent said would vote to stay in the EU, 19 per cent to leave, and 32 per cent said they did not know.

[2] European Commission, “Public opinion in the European Union”, in Standard Eurobarometer 90 (Autumn 2018), p. 43-44, 90-94, https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/survey/getsurveydetail/instruments/standard/surveyky/2215. In this poll, 36 per cent of Italians said they trusted the EU as a whole and the European Commission, 32 per cent the Council of the EU, 44 per cent the European Parliament, and 28 per cent and 27 per cent their national government and parliament respectively.

[3] This observation is based on the Eurobarometer opinion polls for the same period for each member state.

[4] Erik Jones and Matthias Matthijs, “Democracy without Solidarity: Political Dysfunction in Hard Times”, in Government and Opposition, Vol. 52, No. 2 (April 2017), p. 185-210, https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.47.

[5] Giuseppe Di Taranto, “Oltre le polemiche politiche. Ecco come l’Euro sbarcò in Italia”, in LUISS Open, 8 January 2018, https://open.luiss.it/?p=3928.

[6] Council of the European Union, The European Council in 2011, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union, January 2012, https://doi.org/10.2860/37641.

[7] Tim Dixon et al., Attitudes towards National Identity, Immigration and Refugees in Italy, More in Common, August 2018, https://www.moreincommon.com/italy-report1.

[8] Honor Mohony, “Prodi Calls Stability Pact ‘Stupid’”, in EUobserver, 17 October 2002, https://euobserver.com/economic/8008.

[9] A DEMOS poll showed that 8 out of 10 Italians were “positive” towards the new Monti government, and he personally enjoyed the trust of 84 per cent of citizens. Ilvo Diamanti, “Una fiducia da record per il premier. Otto su dieci promuovono Monti”, in Repubblica, 20 November 2011, http://demos.it/a00653.php.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, luglio 2019, 7 p. -

In:

-

Numero

19|48

Tema

Tag

Contenuti collegati

-

Ricerca21/05/2015

Open European Dialogue (già Mercator European Dialogue)

leggi tutto