China’s Push-in Strategy in the Arctic and Its Impact on Regional Governance

Since the early 2000s, Beijing’s interest in the Arctic increased. In 2013, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was admitted as one of the Arctic Council’s permanent observers, the main regional forum. The real turning point, however, was in 2018 when China published a White Paper regarding its policy and goals over the Arctic.[1] In the document, Beijing defined itself as a “near-Arctic state” and set out the ambition to launch a Polar Silk Road. An examination of the reasons and strategies underlying the Chinese interest in the Arctic helps understand its possible impact on regional governance dynamics, and how this contributes to making the Arctic a more global environment.

The Arctic’s untapped potential

In the last two decades, international attention to the Arctic environment and ecology has intensified, increasingly turning its governance into a global issue. In parallel, the enormous potential of Arctic resources has fuelled the growing interest of states in the region. The Arctic is home to 13 per cent and 30 per cent of undiscovered oil and natural gas respectively, as well as large amounts of raw materials and mineral resources.[2]

Against this backdrop, the PRC defines itself as a near-Arctic state, first and foremost because climate crisis-related issues in the Arctic have a relevant impact on China. Indeed, research highlights that the melting of Arctic Sea ice has contributed to significant alterations in the Chinese climate (for example, heavy snowstorms in 2007 and 2008 or haze pollution in 2013).[3]

However, China’s interest in the Arctic moves from other types of considerations as well. Beijing must expand its energy supply to ensure its economic growth. China’s dependence on imported oil is currently over 70 per cent and predicted to increase further in the coming years, while imports account for more than 40 per cent of the country’s total natural gas supply.[4] Hence, the Arctic may significantly contribute to Chinese energy security.

Furthermore, the melting of Arctic Sea ice allows China to take advantage of new Arctic Sea lanes, such as the Northern Sea Route, which connects Asia to Europe. This is shorter and less expensive than the conventional Suez Canal route and would provide an effective alternative to China’s over-reliance on congested trade through the Malacca Strait and the associated incidents of piracy.

Arctic governance: A strategic matter

The Arctic, however, is not just a high-potential territory, it is a region where states, especially great powers, can exercise influence on discussions concerning global issues (first and foremost, environmental and climate ones).

It is widely acknowledged that Xi Jinping’s China strives to be recognised as a great power in the international system by being present in all regions and institutions considered strategic for global governance – including the Arctic Council. As the PRC seeks to become a more prominent player in global governance, four distinct paths for transformation have been identified as possible for Beijing: complier, reluctant member, bystander, and push-in strategy. The most relevant for Chinese-Arctic relations is the latter, which is applicable to the “cases where China is still excluded by the global governing institution in a specific issue area”.[5] Indeed, Beijing must conduct push-in initiatives to have a say in Arctic matters. Although China is not a full member of the Arctic Council, its admittance as a permanent observer in 2013 enabled Beijing to pursue push-in measures. It obtained a voice in the decision-making process by gaining the opportunity to speak and propose projects during Council sessions. Since full admission is not possible in the short term, China must follow complementary push-in strategies to augment its status. Therefore, Beijing has developed its own rhetoric on Arctic issues and begun bilateral relations (mainly of an economic nature) with Arctic states.

China’s Arctic policy

According to the 2018 White Paper, Beijing’s political objectives in the Arctic are protecting, developing and participating in regional governance.[6] To achieve these goals, the PRC’s Arctic policy commits to respecting and promoting international law as its main priority. Since Beijing is known to be an outsider state in the Arctic, it strategically set itself in a prominent position in regional governance through the international agreements to which it belongs.[7] This strategy has become a rhetorical tool to validate Chinese presence in the Arctic. Already in 2015, at the opening ceremony of the third Arctic Circle Assembly, Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a speech stating that “the legitimate concerns of non-Arctic countries and the rights they enjoy under international law in the Arctic and the collective interests of the international community should be respected”.[8] Such rhetoric could be supported by other non-Arctic countries in favour of their interests in the region. This seems to be India’s case, which following Beijing’s example, published its Arctic policy in 2022. In the document, New Delhi expressed its intention to increase its engagements in the Arctic region and echoed Chinese rhetoric on the need for all parties to respect international law.[9]

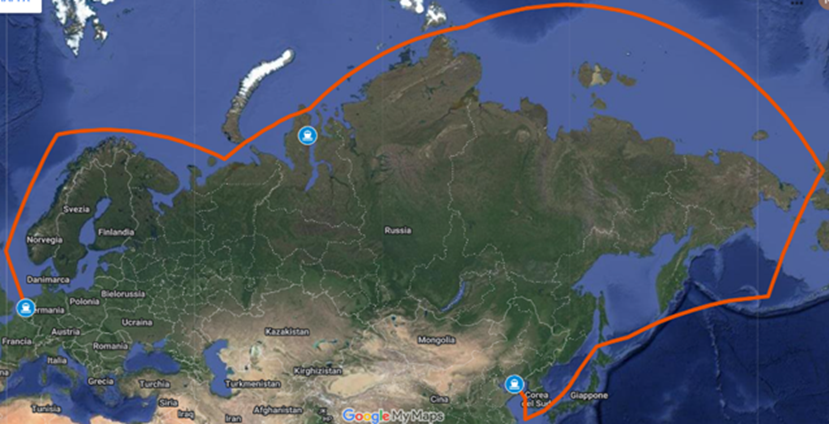

As underlined in the 2018 White Paper, another key tool for implementing China’s ambitions in the High North is the Polar Silk Road. This is the Arctic extension of the Belt and Road Initiative and outlines a plan to encourage the construction of infrastructure in the Arctic, such as ports and transit lines. The proposed route goes via Japan, crosses the Bering Sea and the Northern Sea Route over Russia, passes through the Norwegian Sea, and arrives in the Netherlands (Figure 1).

Figure 1 | The Polar Silk Road

China’s bilateral Arctic diplomacy – and the pushback against it

To develop the Polar Silk Road and its push-in into the Arctic affairs, China has developed relations with the Arctic states, above all, Russia, Iceland and Greenland.

Following Western sanctions imposed on Russia due to the Ukraine crisis in 2014, Moscow and Beijing have grown closer as strategic allies, and the Arctic has gradually turned into a long-term cooperation region. Russia is a relevant player in the Arctic Council due to its extent and proximity to the Arctic Circle. After 2014, the PRC started to invest in the Yamal project, a joint venture around a liquified natural gas plant located in the North-East of the Yamal Peninsula, in northwest Siberia. In 2016, Chinese banks loaned 12 billion US dollars to the plant, effectively stepping in as a potential lender and covering two-thirds of the project’s external financing demands.[10] China’s National Petroleum Corporation and the Chinese company Silk Road Fund now have a 20 per cent and 9.9 per cent share in the project, respectively.[11] The Yamal plant is paramount because it is one of the Polar Silk Road’s initial projects. It showcases Beijing’s commitment to providing logistical support, such as port building and infrastructure in the Arctic; indeed, Chinese engineers have been involved in the development of infrastructure in the Yamal Peninsula, including a Chinese-made polar drilling rig. Moreover, in April 2023, the Russian and Chinese Coast Guard signed an Arctic cooperation agreement to strengthen maritime law and collaborate on joint exercises in the future.[12] In parallel, pre-existing cooperation between Russia’s and other Arctic states’ coast guards through the Arctic Coast Guard Forum was suspended as a result of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, boosting the role of Beijing as a strategic partner for Moscow.[13]

Meanwhile, in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, China emerged as an ideal commercial partner for Iceland, whose economy had been seriously harmed. The two countries’ free-trade agreement signed in 2013 strengthened China’s status and influence in the Arctic. This partnership is centred on energy and fisheries. Iceland delivers technology and highly qualified professionals in well-drilling, as well as technical support, while Beijing provides access to one of the largest markets in the world.[14]

Greenland, the closest land to the North Pole, is also an important component of China’s Arctic strategy. Its location makes it critical for any state seeking access to the Arctic. Chinese firms have expressed interest in investing in Greenland, especially its mineral reserves, which are becoming more accessible due to climate change. More specifically, a Chinese company established a partnership with an Australian firm to develop rare earth and uranium mining in Kvanefjeld, in Southern Greenland, in 2016.[15]

Nonetheless, China’s push-in strategies in the Arctic are also raising concerns in the US. Indeed, in 2019, during the Arctic Council’s Ministerial Meeting in Finland, Washington warned the other Arctic states about China’s economic and military ambitions over the region. The US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo pointed out the substantial investment of China in the Arctic states – estimated to be at 90 billion US dollars between 2012 and 2017 – and voiced the Pentagon’s worries about Beijing possibly using its presence in the Arctic to reinforce its military activity.[16] NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg shared such concerns, saying that China is expanding its reach over the High North through its “near-Arctic state” declaration, investments and partnership with Moscow.[17] According to Stoltenberg, while the Arctic used to be characterised by low tensions, this is now changing due to its enormous opportunities and the resulting global competition over them.[18] Also as a result of this push-back, some scholars highlight that the Polar Silk Road’s future seems now uncertain since there is a significant gap between its stated objectives and concrete achievements. Indeed, the PRC’s projects in the Arctic are suffering from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Arctic states stepping back: for example, Greenland eventually halted the Kvanefjeld project in 2021.[19]

China and the making of a global space?

Through the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Arctic governance entered a new phase, shifting from a separate territory with its policy agenda to a region with tighter linkages to the rest of the world. Today, notwithstanding the one-year suspension due to Western-Russia tensions related to the war against Ukraine, the Arctic Council is busier than ever because of the presence of China and other observer states, including India, South Korea and Japan.[20] In the future, China’s involvement in the Arctic and its attempt to build the Polar Silk Road will present new opportunities as well as challenges to the Arctic governments. As a non-Arctic country, the success of China’s Arctic policy will be determined by its push-in strategy, which includes the capacity to deepen regional cooperation, a focus on international agreements and associated rhetorical tools, as well as bilateral and economic diplomacy, and its capacity to deal with the pushback against it. However successful the PRC’s strategy in the Arctic will eventually be, it is nonetheless already contributing to reshaping Arctic governance. The same fact that China–US tensions are emerging in the Arctic is evidence of how China’s Arctic Policy is contributing to “reframe[ing] the Arctic as a global space”.[21]

Matilde Biagioni holds a Master’s degree in International Relations from Roma Tre University and is currently Chief Coordinator of the Asia-Pacific team for the Opinio Juris review.

[1] Chinese State Council, China’s Arctic Policy, 26 January 2018, https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm.

[2] European Commission’s platform Knowledge4Policy, Earth Observation for the Arctic, last updated 2 May 2023, https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/node/61970.

[3] Kong Soon Lim, “China’s Arctic Policy & the Polar Silk Road Vision”, in Justin Barnes et al. (eds), China’s Arctic Engagement. Following the Polar Silk Road to Greenland and Russia. Selected Articles from the Arctic Yearbook, Ontario, North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network, 2021, p. 38-62 at p. 42, https://www.naadsn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NAADSN-engage3-ChinaAY-JB-EXP-LH-PWL-upload-rev.pdf.

[4] Haiyu Xie, “China’s Oil Security in the Context of Energy Revolution: Changes in Risks and the Hedging Mechanism”, in American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, Vol. 11, No. 9 (September 2021), p. 984-1008, https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2021.119060; Victoria Zaretskaya and Faouzi Aloulou, “China’s Natural Gas Consumption and LNG Imports Declined in 2022, Amid Zero-COVID Policies”, in Today in Energy, 1 June 2023, https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=56680.

[5] Fengshi Wu, “China’s Ascent in Global Governance and the Arctic”, in Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Series 6: Political Science. International Relations, No. 2 (June 2016), p. 118-126 at p. 121, https://doi.org/10.21638/11701/spbu06.2016.211.

[6] Chinese State Council, China’s Arctic Policy, cit.

[7] Matthew D. Stephen and Kathrin Stephen, “The Integration of Emerging Powers into Club Institutions: China and the Arctic Council”, in Global Policy, Vol. 11, Suppl. 3 (October 2020), p. 51-60, https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12834.

[8] Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Video Message by Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Opening Ceremony of the Third Arctic Circle Assembly, 17 October 2015, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/2461_663310/201510/t20151017_468585.html.

[9] Indian Government, India’s Arctic Policy: Building a Partnership for a Sustainable Development, 17 March 2022, https://www.moes.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-05/India_Arctic_Policy_2022.pdf.

[10] Rashmi B. Ramesh, “China in the Arctic: Interests, Strategy and Implications”, in ICS Occasional Papers, No. 27 (March 2019), p. 13, https://www.icsin.org/publications/china-in-the-arctic-interests-strategy-and-implications.

[11] Atle Staalesen, “Chinese Investors Could Finance Murmansk LNG”, in The Barents Observer, 7 June 2023, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/node/11361.

[12] Jiang Chenglong, “Coast Guard, Russia Security Service Sign Joint MoE”, in China Daily, 27 April 2023, https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202304/27/WS644a5c70a310b6054fad038c.html.

[13] Thomas Nilsen, “Russia’s Coast Guard Cooperation with China Is a Big Step, Arctic Security Expert Says”, in The Barents Observer, 28 April 2023, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/node/11193.

[14] Iceland Government website: Free Trade Agreement between Iceland and China, https://www.government.is/topics/foreign-affairs/external-trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreement-between-iceland-and-china.

[15] Rashmi B. Ramesh, “China in the Arctic”, cit., p. 15.

[16] US Department of State, Looking North: Sharpening America’s Arctic Focus, 6 May 2019, https://2017-2021.state.gov/looking-north-sharpening-americas-arctic-focus.

[17] NATO, Joint Press Conference with NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and the Prime Minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, 26 August 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_206908.htm.

[18] Jens Stoltenberg, “NATO Is Stepping Up in the High North to Keep Our People Safe”, in The Globe and Mail, 24 August 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_206894.htm.

[19] Marc Lanteigne, “The Rise (and Fall?) of the Polar Silk Road”, in The Diplomat, 29 August 2022, https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-polar-silk-road.

[20] Canada et al., Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine, 3 March 2022, https://www.state.gov/?p=320209.

[21] Matthew D. Stephen and Kathrin Stephen, “The Integration of Emerging Powers into Club Institutions”, cit., p. 58.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, settembre 2023, 6 p. -

In:

-

Numero

23|41