Israel/Palestine and the Normative Power of the “Global South”

In the past few years, International Relations scholars have reflected about change in global order in three main streams of thought. The realist stream has pointed out that the world is increasingly multipolar,[1] focusing on major powers: the US, China, the EU and Russia. Liberal/constructivist scholars have explored the crisis and challenges of and within the liberal international order.[2] In this vein, John Ikenberry has recently delineated a scenario of three worlds: that is, the “Global North” (led by the US and, to some degree, the EU), the “Global East” (led by China and Russia) and the “Global South”.[3] The latter, Ikenberry argues, is without a big power leadership and appears somewhat more passive, whilst the other two “Globals” are engaged in a competition for the “Global South”. In this competition, he argues, the liberal international order has a comparative advantage. Finally, the Global IR stream, and Amitav Acharya in particular, have proposed the concept of a multiplex world: a more plural and de-centred world where we, instead, observe an increase in the interaction capacity of middle and small powers as well. By interaction capacity, Acharya et al. mean “the relative ability of nations to organize cooperation”.[4]

What all these streams agree upon is that the international order is in transformation. This transformation will be significantly shaped by how a variety of actors negotiate the basic principles, rules and institutions that govern their interactions and relations. Central in such negotiations are international crises. As Ikenberry has pointed out, the “Russian invasion of Ukraine has sparked a global debate on world order”. This is clearly the case when looking at world order from the viewpoint of the US, EU and Russia. The Global South has also intervened in the debate over the Russia-Ukraine war, calling for food security and largely supporting international law in votes in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), whilst seeing it as a “war over the European security order”.[5]

Looking at the global order from the postcolonial world, a much more important crisis for order negotiation and restructuring is the war in Israel/Palestine.[6] Here, the global dynamic is completely different: the Global South has enacted its presence in the normative ordering of the international, whilst the West is divided, and Russia, as well as China, are rather passive. So, on this war, a central negotiation is taking place, mainly between the Global South and the West, that will have an impact on the global normative ordering as profound as the negotiations surrounding the Russia-Ukraine war.

‘Land for peace’ and the retreat from international law

This negotiation is, of course, not entirely new. In the context of the decolonisation process, from the 1960s to the 1980s, the non-aligned movement was central in establishing in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) that, just like Israelis, also Palestinians have inalienable individual and collective rights, including an unconditional right to statehood. In 1988, UNGA Resolution 43/177 acknowledged the proclamation of the State of Palestine and affirmed the need to enable the Palestinian people to exercise their sovereignty over their territory occupied since 1967. UNGA so contested the US-led peace process which, instead, was guided by the ‘land for peace’ paradigm that had emerged in 1967. Unlike the Suez Crisis in 1956, when the US and the USSR had forced France, the UK and Israel to retreat from the Sinai in line with international law and the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force, after 1967, the US conditioned such a retreat on peace, so sidelining international law.

Whilst this approach was contested by UNGA, the Arab League and, to some degree, also the European Community in the 1980s,[7] in the 1990s, in the so-called unipolar moment of the liberal international order, the idea of liberal peace-building as a precondition for Palestinian statehood became dominant. Due to the lack of accountability to international law within the peace process, however, as the years went by, the land-for-peace formula looked increasingly obsolete: the occupied Palestinian territory was fractured by Israeli settlements in the West Bank including East Jerusalem – where the settlement population now stands at more than 700,000 –,[8] as well as by the barrier/wall and the separation from Gaza, under full Israeli land, air and sea blockade from 2007 onwards. Amidst this context, the Palestinian leadership decided to take their struggle back to the UN and the mechanisms and institutions of international law.

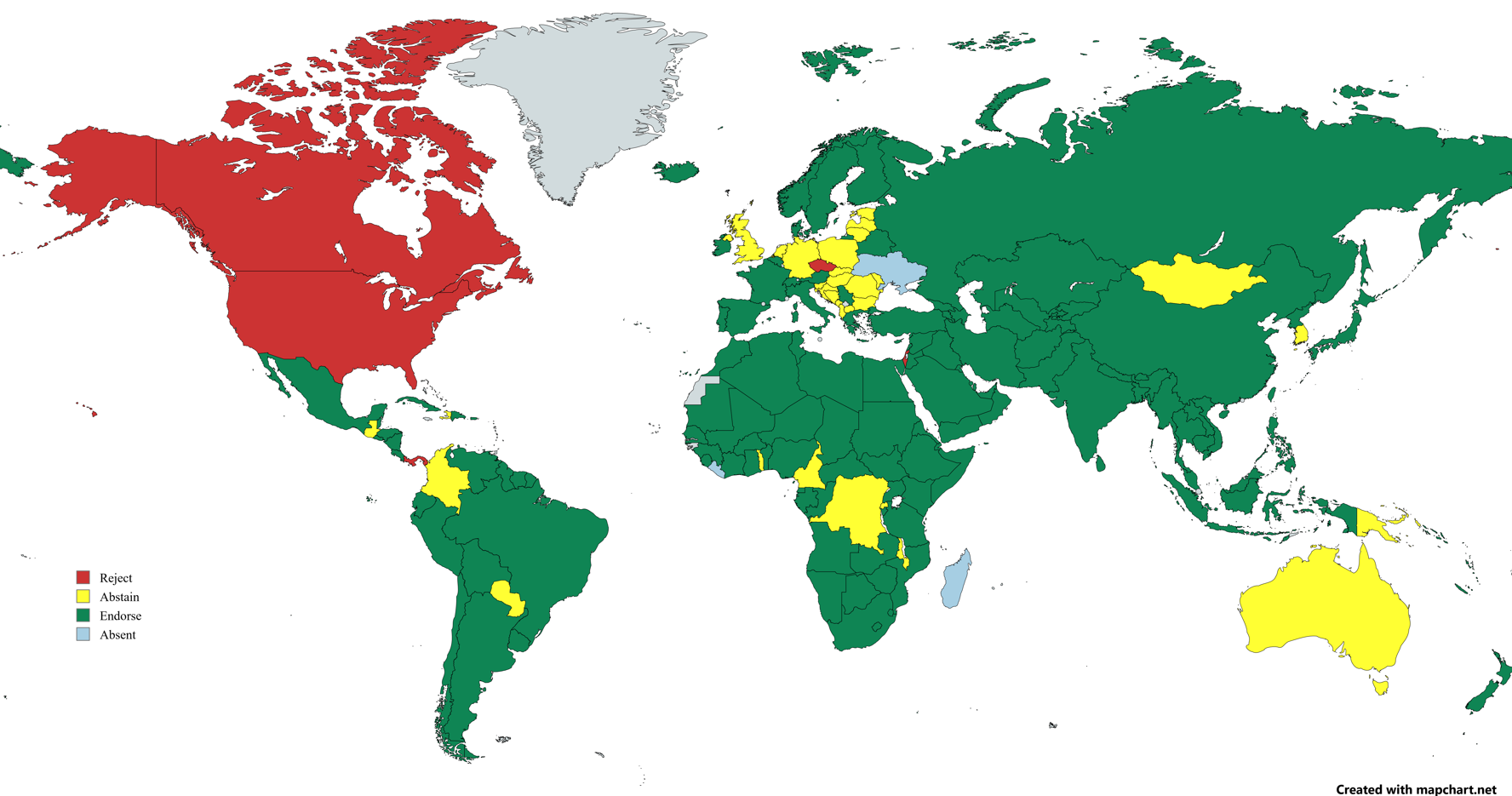

Whilst the West could previously unite under the land-for-peace paradigm, it now had a hard time uniting under the principles and institutions of international law. The division thus set on in 2012, when Palestine applied for non-membership status at the UN (Figure 1).

Figure 1 | UNGA votes Palestine “non-member observer state”, 2012

Source: United Nations, General Assembly Votes Overwhelmingly to Accord Palestine ‘Non-Member Observer State’ Status in United Nations, 29 November 2012, https://press.un.org/en/2012/ga11317.doc.htm.

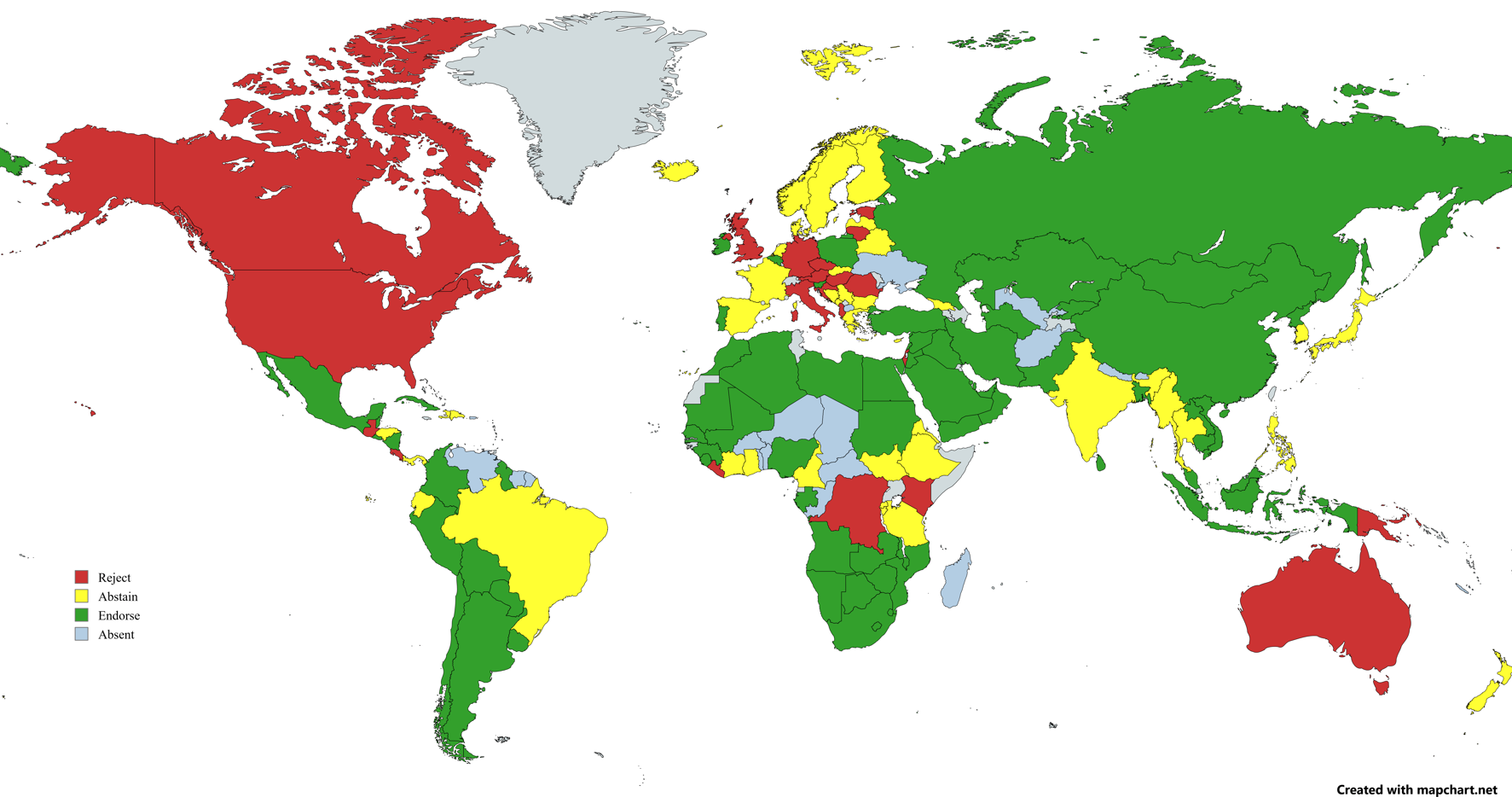

Following this, the EU Foreign Affairs Council sought to dissuade Palestine from signing the Rome Statute.[9] Palestine, nonetheless, moved the case to the International Criminal Court (ICC), which in 2021 asserted its jurisdiction. In response, Germany publicly positioned itself against the ICC claiming it had no jurisdiction,[10] undermining not only the authority of the Court but effectively also seeking to deny Palestinians their right to have their case assessed through a major institution of international law. In 2022, again, the West voted divided (Figure 2) on the UNGA resolution requesting an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the “Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem”.[11]

Figure 2 | UNGA votes “Israeli practices affecting the human rights of the Palestinian people in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem”, 2022

Source: United Nations, Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Including East Jerusalem, Voting Summary, 30 December 2022, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3999158.

This division that runs through the West effectively blocks a position more in line with international law. This became even more evident after the attack on 7 October where Hamas took 250 Israeli hostages and killed 766 civilians, as well as 373 security forces.[12] In response, Israel started an invasion, killing within October alone more than 9,000 Palestinians, of which more than 3,700 children, displacing hundreds of thousands.[13] Besides the large-scale destruction of housing, health and educational infrastructure, the Israeli government also announced the impeding of relief supplies, using starvation of civilians as collective punishment and method of warfare. In the only EU Council Conclusions on which the member states could so far agree upon, on 23 October 2023, the EU condemned Hamas “for its brutal and indiscriminate terrorist attacks across Israel” but did not condemn Israel for its brutal and indiscriminate bombing of Gaza, only stating generically that the response should be in line with international law.[14] It also failed to call unequivocally for a ceasefire despite the massive death toll and destruction.

Only in mid-February, with more than 30,000 Palestinians in Gaza killed, 12,300 of which children,[15] and most of the Israeli hostages, including two children, still being held by Hamas,[16] and amidst mounting fears of forcible displacement of 1.5 million Palestinians sheltering in Rafah into the Sinai,[17] did 26 EU member states (without Hungary) ask Israel to halt its military action in Rafah. They did, however, not outline what impact a military action would have on EU-Israel relations,[18] and similarly failed to pressure Israel into allowing humanitarian aid via land crossings into Gaza, where the World Health Organization has warned of catastrophic famine.[19]

The normative vacuum that has been created by the US and the EU has, it should be noted, not been used by Russia or China, which have remained rather passive. Instead, it has been the Global South that has moved into this normative vacuum.

The Global South takes action

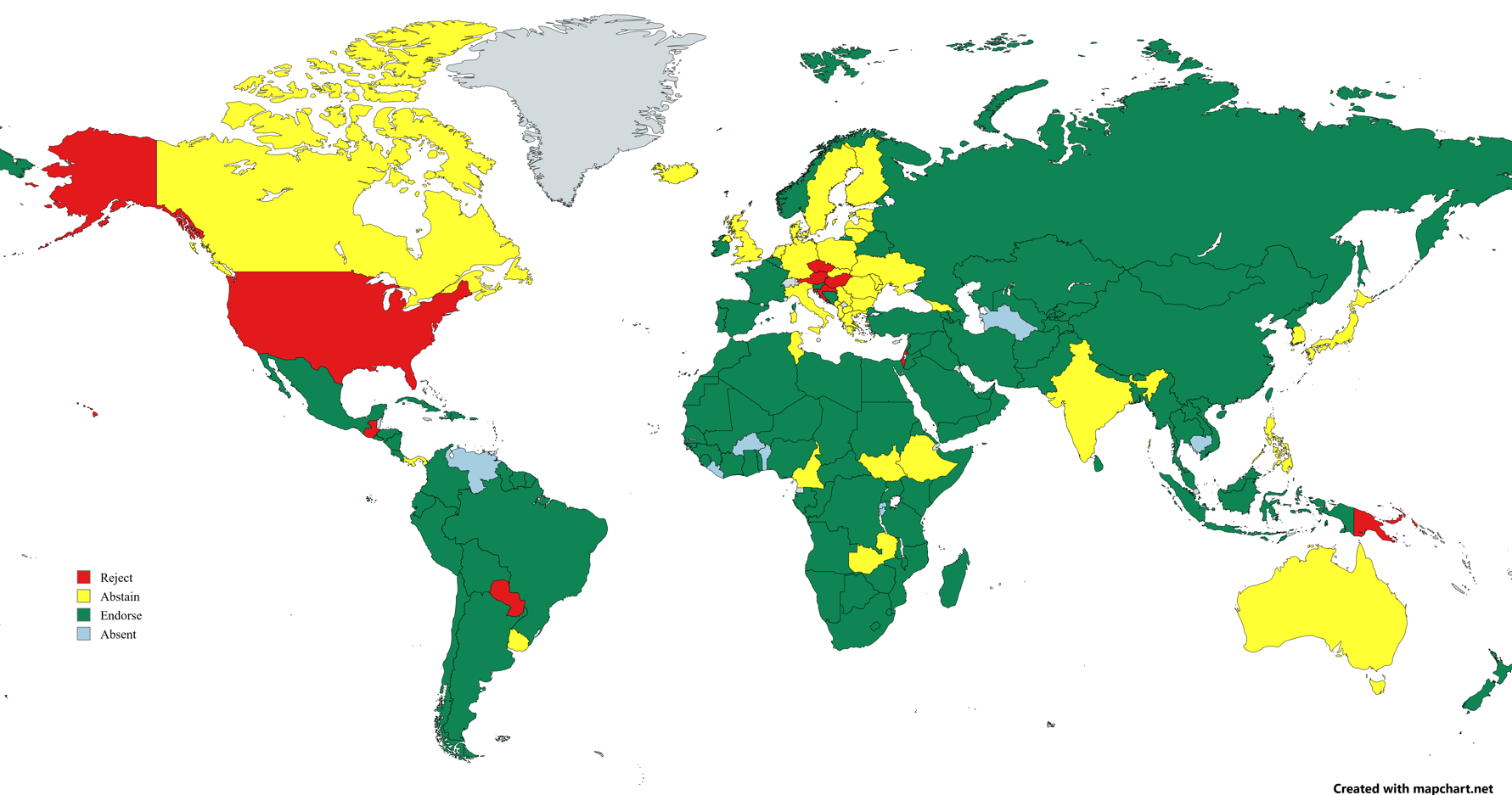

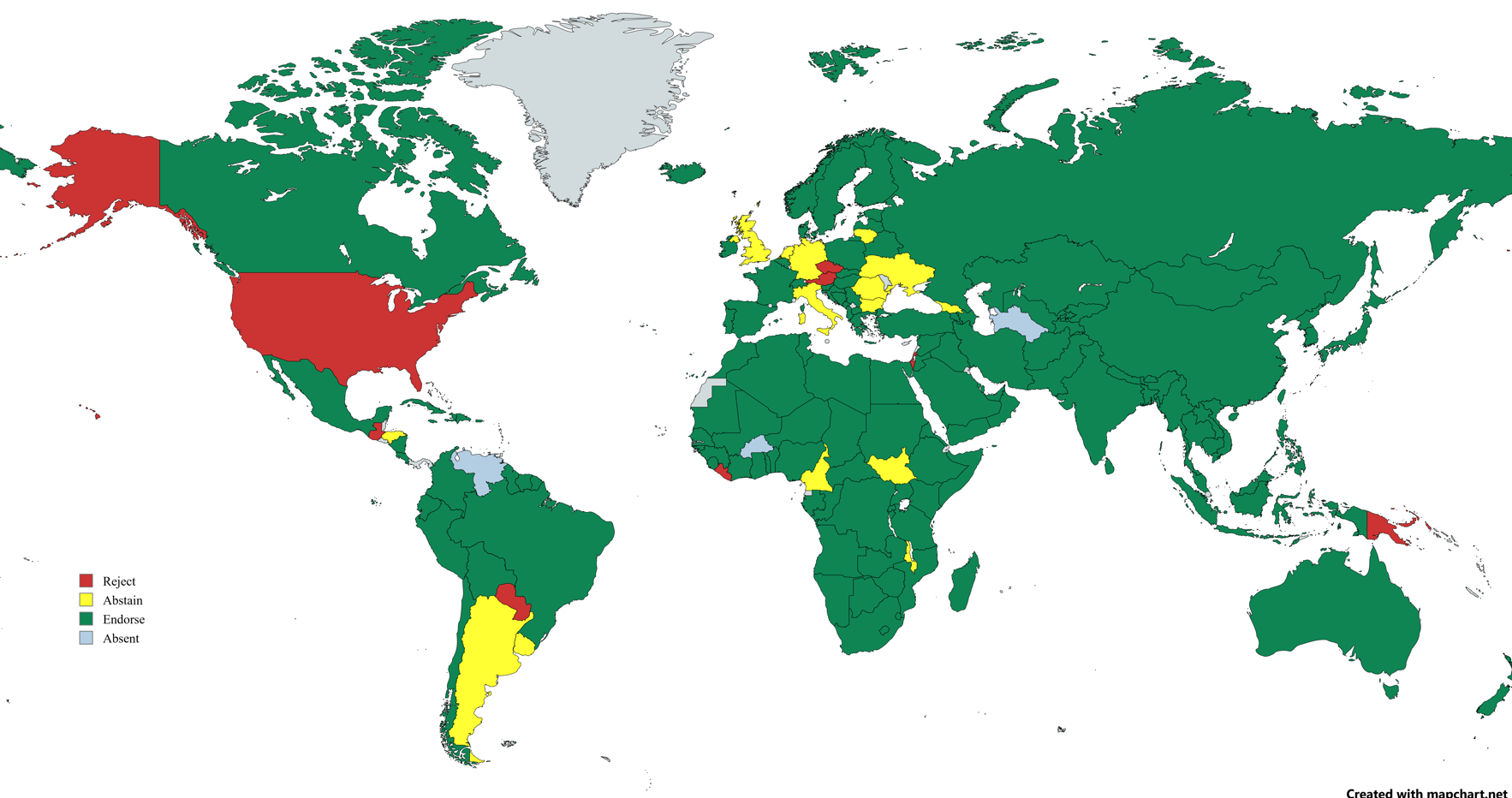

Whilst Global South countries had been rather cohesive in their votes in favour of supporting the application of mechanisms of international law to Israel/Palestine before 7 October (see Figures 1 and 2), these voting patterns became more robust afterwards (see Figures 3 and 4). Furthermore, rather than simply backing Palestinian initiatives in international institutions, various Global South countries now began to take initiatives within these institutions themselves.

Figure 3 | UNGA votes ceasefire resolutions, 26 October 2023

Source: United Nations, UN General Assembly Adopts Gaza Resolution Calling for Immediate and Sustained ‘Humanitarian Truce’, 26 October 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142847.

Figure 4 | UNGA votes ceasefire resolutions, 12 December 2023

Source: United Nations, UN General Assembly Votes by Large Majority for Immediate Humanitarian Ceasefire during Emergency Session, 12 December 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/12/1144717.

Algeria as an elected UNSC member became active in drafting resolutions, and filed a complaint at the ICC (together with Colombia). Qatar appeared as a key mediator at a time when the US and the EU had largely lost this status, and hence their interaction capacity or relative ability to exercise political leadership and organise cooperation. Saudi Arabia published a clear rebuttal of the US in a statement where it insisted on the recognition of a Palestinian state within the 1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital before proceeding with normalisation. Most importantly, however, South Africa instituted – with broad support from a large majority of states in the Global South (but notably from neither China nor Russia) – proceedings against Israel at the ICJ concerning alleged violations by Israel of its obligations under the Genocide Convention in relation to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. Whilst some EU member states were positive (Belgium, Ireland) or neutral (France, Spain), Germany announced its intention to intervene in the South Africa versus Israel case at the ICJ on Israel’s behalf, issuing a statement which implicitly accused South Africa of an instrumentalisation of the Convention. This triggered a diplomatic incident where late Namibian President Hage Geingob strongly criticised “the shocking decision communicated by the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany”.[20] In its order on 24 January 2024, the Court concluded that “at least some of the acts and omissions alleged by South Africa to have been committed by Israel in Gaza appear to be capable of falling within the provisions of the Convention”.[21] Shortly afterwards, Nicaragua instituted proceedings against Germany before the ICJ for alleged violations by Berlin of its obligations deriving from the Genocide Convention, the Geneva Conventions and other norms of international law.[22]

The indefensible West

In light of this “crisis of humanity”,[23] Western players must be aware of what their position means for a larger transforming global order. Two conclusions are pertinent in this respect. First, it is evident that a multiplex world is in the making where actors other than the big powers are enacting their normative presence in the international arena. South Africa has shown an impressive leadership in this respect, and might have paved the way for others to follow suit. It also holds normative power with its model of post-Apartheid co-existence (similar to the normative power which the EU once held with its model of co-existence in Europe). Second, the idea that the “Global North” has an advantage today in the international competition on visions of order must be strongly qualified. The normative power that the liberal international order as a vision can hold in a multiplex world depends on the West’s consistent adherence to the postwar edifice of principles, rules and institutions of international law that does not only embody significant lessons learnt from European history, but without which the West loses its interaction capacity. Europe is – to quote Aimé Césaire –, once again, indefensible.[24]

Daniela Huber is Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department of Roma Tre University. She is scientific advisor of the Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa Programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), which she led from 2019 to 2022, and co-editor of The International Spectator.

[1] John J. Mearsheimer, “Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order”, in International Security, Vol. 43, No. 4 (Spring 2019), p. 7-50, https://doi.org/10.1162/isec_a_00342.

[2] David A. Lake, Lisa L. Martin and Thomas Risse, “Challenges to the Liberal Order: Reflections on International Organization”, in International Organization, Vol. 75, No. 2 (Spring 2021), p. 225-257, DOI 10.1017/S0020818320000636.

[3] G. John Ikenberry, “Three Worlds: The West, East and South and the Competition to Shape Global Order”, in International Affairs, Vol. 100, No. 1 (January 2024), p. 121-138, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad284. These terms are somewhat essentialising historically diverse and socially, economically and politically complex geographies. This commentary uses the term the “West” that includes countries located in areas of the world which are not in the North (such as Australia). It uses the term “Global South” to describe the postcolonial world, whilst it also discusses particular positions by postcolonial countries (China and South Africa). Stewart Patrick and Alexandra Huggins, “The Term ‘Global South’ Is Surging. It Should Be Retired”, in Carnegie Commentaries, 15 August 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/90376.

[4] Amitav Acharya, Antoni Estevadeordal and Louis W Goodman, “Multipolar or Multiplex? Interaction Capacity, Global Cooperation and World Order”, in International Affairs, Vol. 99, No. 6 (November 2023), p. 2339-2365, https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiad242.

[5] Lorenzo Kamel, “Has the Russo-Ukraine War Really Changed the Global Order?”, in The Buzz, 14 April 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/node/201835.

[6] It should be noted that this war is not confined to Gaza. In the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, Amnesty International has noted a “spike in use of unlawful lethal force by Israeli forces”, and Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) reported a surge in detentions of Palestinians, and inherent practices of “forced disappearances, torture, and severe violations of human rights”. Furthermore, the war also takes place in Israel and Southern Lebanon with rocket attacks and air strikes. Amnesty International, Shocking Spike in Use of Unlawful Lethal Force by Israeli Forces against Palestinians in Occupied West Bank, 5 February 2024, https://www.amnesty.org/en/?p=206744; PHR, Systematic Violation of Human Rights: The Incarceration Conditions of Palestinians in Israel Since October 7, February 2024, https://www.phr.org.il/en/?p=17797.

[7] See the Venice Declaration of 1980 that insists on de-occupation and international law. European Council, Venice Declaration, 13 June 1980, https://eeas.europa.eu/mepp/docs/venice_declaration_1980_en.pdf.

[8] European Union Representative to West Bank and Gaza Strip, UNRWA, 2021 Report on Israeli Settlements in the Occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. Reporting period -January-December 2021, 20 July 2022, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/416884_en.

[9] Council of the European Union, Council Conclusions on the Middle East Peace Process, 10 December 2012, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/foraff/134140.pdf.

[10] Stefan Talmon, “Germany Publicly Objects to the International Criminal Court’s Ruling on Jurisdiction in Palestine”, in GPIL blog, 11 February 2021, https://gpil.jura.uni-bonn.de/?p=2824.

[11] International Court of Justice, Case 186: Legal Consequences Arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (Request for Advisory Opinion), 19 January 2023, https://www.icj-cij.org/case/186.

[12] “Israel Social Security Data Reveals True Picture of Oct 7 Deaths”, in France 24, 15 December 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20231215-israel-social-security-data-reveals-true-picture-of-oct-7-deaths.

[13] Euro-Med Monitor [@EuroMedHR], “Statistics on the Israeli Attack on the Gaza Strip”, in Twitter, 31 October 2023, https://twitter.com/EuroMedHR/status/1719406267620270215.

[14] European Council, European Council Conclusions on Middle East, 26 October 2023, https://europa.eu/!jjTCT7.

[15] Philippe Lazzarini [@UNLazzarini], “Staggering. The Number of Children Reported Killed in Just over 4 Months in #Gaza Is Higher than the Number of Children Killed in 4 Years of Wars around the World Combined”, in Twitter, 12 March 2024, https://twitter.com/UNLazzarini/status/1767618985397272831.

[16] Website of the Hostages and Missing Families Forum, https://stories.bringthemhomenow.net.

[17] Jonathan Adler, “South into the Sinai: Will Israel Force Palestinians Out of Gaza?”, in Sada, 31 October 2023, https://carnegie-mec.org/sada/90869.

[18] European Union External Action Service, Israel/Palestine: Statement by the High Representative on a Planned Israeli Military Operation in Rafah, 16 February 2024, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/438359_en.

[19] World Health Organization, Famine in Gaza Is Imminent, with Immediate and Long-Term Health Consequences, 18 March 2024, https://www.who.int/news/item/18-03-2024-famine-in-gaza-is-imminent--with-immediate-and-long-term-health-consequences.

[20] Stefan Talmon, “Germany Rushes to Declare Intention to Intervene in the Genocide Case Brought by South Africa against Israel before the International Court of Justice”, in GPIL blog, 15 January 2024, https://gpil.jura.uni-bonn.de/?p=4062.

[21] International Court of Justice, Case 192: Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in the Gaza Strip (South Africa v. Israel). Summary of the Order of 26 January 2024, https://www.icj-cij.org/node/203454.

[22] International Court of Justice, Case 193: Proceedings Instituted by the Republic of Nicaragua against the Federal Republic of Germany. Application Instituting Proceedings and Request for the Indication of Provisional Measures, 1 March 2024, https://www.icj-cij.org/index.php/node/203820.

[23] United Nations, Press Conference by Secretary-General António Guterres at United Nations Headquarters, 6 November 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sgsm22021.doc.htm.

[24] Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, New York, Monthly Review Press, 2000, p. 32.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, marzo 2024, 8 p. -

In:

-

Numero

24|14