Training, Reskilling, Upskilling: How to Create Jobs through the Green Transition

The energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources is the next great challenge that the EU will face. One key concern is the transformation of the labour market. As we move away from fossil fuels, some polluting “brown” sectors, such as coal mining, will decline, affecting 3-10 per cent of jobs across the EU, but more than 20 per cent of jobs in certain regions.[1] The green transition will also be a source of new jobs: delivering on the EU’s 2030 climate pledges could lead to a net increase of up to 884,000 jobs in climate-friendly and neutral sectors.[2] Other brown sectors, such as automotive, will transform.[3] The working-age population, however, will need training to tailor their existing skills to the requirements of the new or transformed jobs. According to a 2022 Special Eurobarometer, 38 per cent of respondents believe they lack the skills to support the green transition.[4] Reskilling and upskilling will thus be needed to prevent labour shortages in the future.

To bridge the gap between employers grappling with skill shortages and workers facing displacement, we propose to create training programs tailored to equip working-age citizens with the skills demanded by emerging sectors, which will help ensure a smooth transition. Policy action will be necessary to navigate this process effectively, fostering a fair transition and preventing potential political backlash. Proactively managing this transformation towards a green economy will contribute not only to creating pathways to employment but also to cultivating a more resilient and sustainable future for all EU citizens.

The EU’s Skills Agenda for 2025

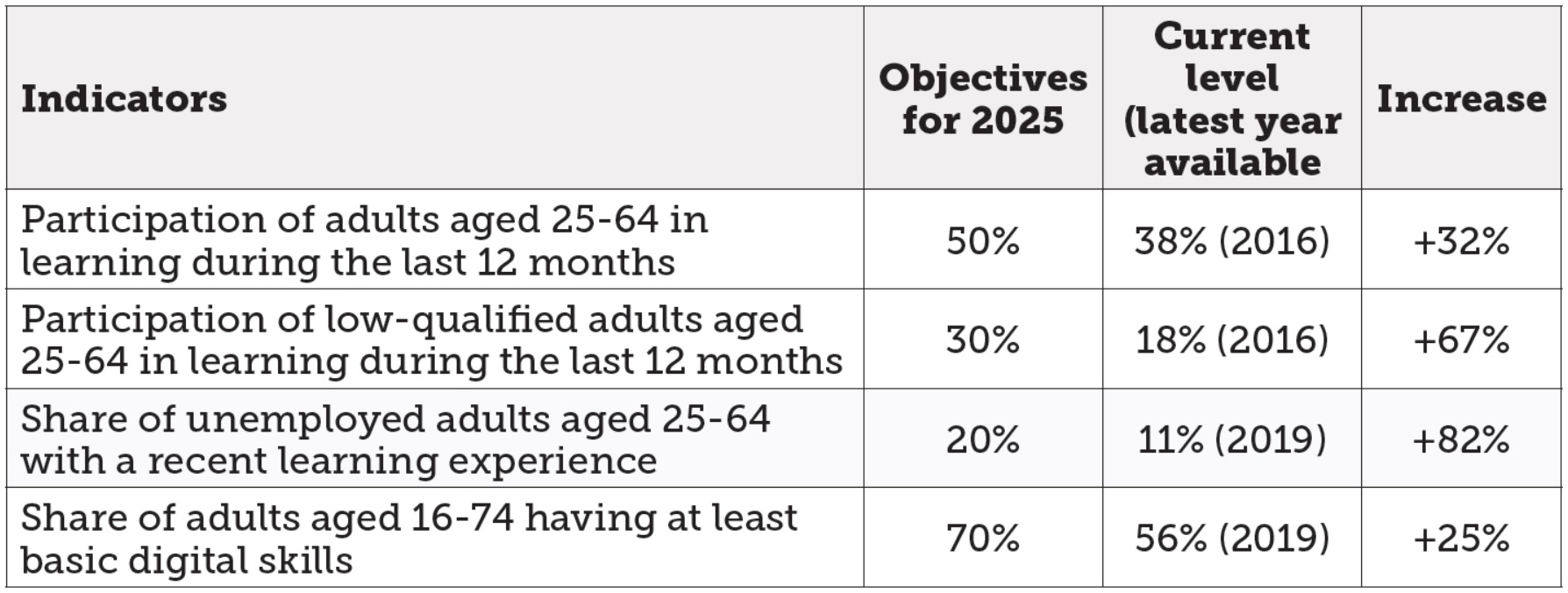

In the face of these challenges, the EU is currently developing a framework to promote life-long learning and skills adaptation for the green transition. In 2020, the Commission announced a new Skills Agenda for 2020-2025,[5] which aimed to (i) obilise stakeholders to collaborate through a Pact for Skills; (ii) design a strategy to improve the matching of skills to jobs; (iii) support lifelong learning by promoting national actions and vocational and education training (VET); and (iv) foster financial investment. The targets set by the Skills Agenda for 2025 are summed up in Table 1. The Skills Agenda aligns with the European Pillar of Social Rights objectives and builds on the initiative to create an inclusive and resilient European Education Area. It has recently gained visibility following the European Year of Skills (EYS) 2023-2024, which raised awareness regarding lifelong learning.[6]

Table 1 | Skills Agenda for 2025 targets

Source: European Commission, European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience, cit., p. 20.

Against this backdrop, the policies we recommend in the following could help reach the 2025 targets as well as unlock progress for the next Skills Pact to be drafted after the 2024 EU elections.

Strengthening the EU’s strategy for training: The Green Energy Erasmus Programme

The future workforce will face many challenges in these new employment conditions and therefore needs decisive support. To this end, the new Commission could propose a Green Energy Erasmus Programme (GEEP). This would entail mobility programmes tailored to apprentices in the energy sector so that young Europeans can be specifically trained for upcoming energy jobs.[7] In direct partnership with small and medium enterprises and other stakeholders, the GEEP would in parallel support transitioning industries in acquiring qualified workers. To make it profitable to all, a guaranteed minimum salary would be provided for apprentices, and organisations hosting them will benefit from tax breaks.

These new Erasmus opportunities should be available and tailored to students in VET programmes, which represented 8.5 million students in the EU in 2019.[8] As emphasised in the Council recommendation of 2020, VET is a key pillar of education and skills for the green transition.[9] However, research shows that students in VET programmes perform relatively worse than others in the skills needed for green jobs.[10] Therefore, the opportunity to complete work-based training abroad in the green sector through the GEEP would highly benefit their education.

To fund the GEEP, those public-private partnerships (PPPs) may be leveraged that, according to the European Training Foundation, already provide key support for VET centres. These types of partnerships enable all actors involved to contribute to the design of programmes and finance their development. PPPs for VET programmes are not only beneficial for students and training centres but also for private actors who have strong incentives to invest financially in them as they generate opportunities for growth.[11] Such instruments could be encouraged to fund the GEEP and ensure high-stakes collaboration between training centres and private actors in successfully teaching young generations green skills.

Creating training opportunities that are accessible to all and for all

The EU’s training programmes must be as inclusive as possible. The opportunities of the green transition must be shared more fairly by ensuring that groups currently underrepresented in green jobs, such as women and older adults, also take part in training.[12] In close collaboration with stakeholders defending the interests of these groups, more steps need to be taken to promote inclusivity. A few ideas to steer a more inclusive transition may include:

• Provide childcare services during training hours and minimum quotas. Women are underrepresented in energy-intensive industries. They account for 27.7 per cent of the workforce in the electricity sector and 22.2 per cent in transport.[13] The Skills Pact aims to increase women’s participation in STEM fields by raising awareness, but the structural constraints that hinder women’s participation in these sectors need to be addressed with concrete measures, such as free childcare services and minimum quotas for women.

• Remove barriers to entry through financial compensation for programme completion and flexible schedules. Whilst demand for skills training is increasing, studies show that worker participation in such programmes is below average, and low-skilled workers are more likely to find participation difficult.[14] Financial compensation would allow easier programme access to all working-age individuals by ensuring that time away from paid work does not pose a barrier to entry and compensates for potential wage gaps. Flexible schedules allow workers to train whilst continuing their current profession, hence making programmes more accessible to workers.

• Open up specific training programmes for adult and older workers. Adult workers require training focusing on particular skills, rather than participating in ‘complete programmes’.[15] Specific training programmes tailored to their skills gap and oriented towards career guidance must be created in collaboration with businesses that know what skills are required. These programmes would optimally evaluate the green sectors where workers can most easily relocate with their existing skills, and provide focused training for those they still require.

Targeting the right sectors and regions

The effectiveness of the proposed measures depends on the EU’s ability to discern strategic sectors that will grow during the green transition. A study by the Clean Energy Technology Observatory (CETO) indicates that sectors such as heat pumps, biofuels, solar and wind energy are the most promising.[16]

More specifically, it is expected that most jobs in the solar industry will be created by the deployment of solar infrastructure and its installation.[17] For wind energy, manufacturing accounts for a greater share of new employment opportunities. Hence, training programmes and related measures must be focused first and foremost on these rapidly developing sectors and on the segments of the value chain most in need of a labour force.

A different but related issue is the relocation of jobs. Indeed, the impact of the energy transition on the labour market does and will vary across regions depending on the share of employment in brown industries and other dimensions of vulnerability and adaptability.[18] The loss of jobs could lead to emigration from the most affected regions, which in turn would exacerbate the regional differences within countries and the EU at large.

To prevent the decline of carbon-intensive regions and the mass relocation of working-age population, as well as potential political backlash, provisions must be introduced to ensure that new green jobs are created in the same areas where brown jobs are lost. In some of the most affected regions, the jobs lost in the coal mining sector could be replaced by new jobs in renewable energy production. One of the most affected regions, for example, is Greece’s Western Macedonia region, where the coal mining industry employs an important share of workers.[19] This region is suitable for renewable energy production, and has already signed off on solar photovoltaic projects co-financed by the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Facility to be implemented by the end of 2024.[20]

In those regions that are not similarly suitable for renewable production, the accompanying service industries could provide new jobs. This could be ensured through financial incentives, such as power purchasing agreements, infrastructure development, an enabling policy environment and support for R&D and innovation.

Monitoring the programmes and assessing their performance

Continuous performance assessment is quintessential for green skills training since the employment market is set to evolve over time. Whilst some sectors require high-skilled workers today, they will need lower-skilled workers as they progress from the innovation and installation stages to maintenance. The success of any measures taken at the EU level is dependent on effective performance assessment to adapt programmes to the changes in skills requirements.

To this end, the Commission should be tasked with monitoring and evaluating the effects of these policies and present a report following their implementation to the European Parliament and the Council. This could happen in parallel with the report that the Commission is already responsible for regarding the assessment of the EYS.[21] The Commission’s report should also be based on interviews and surveys with participants in training programmes and their employers.

Funding the EU’s reskilling programmes

When discussing the costs of reskilling programmes, it must be borne in mind that, as older workers are overrepresented in brown sectors, the main alternative to reskilling programmes is early retirement. However, early retirement raises significant financial issues for workers who will often not have saved up enough money to support themselves in retirement. The replacement rate of pensions, which expresses the percentage of income that is replaced by pensions upon retirement, is 68 per cent on average in the EU, but only 40 per cent and 59 per cent in Poland and Croatia respectively,[22] two of the countries with the highest rates of employment in brown industries in the EU.[23] These sudden drops in income would have severe consequences for the affected older workers.

Furthermore, a sudden increase in the number of pensioners would put a strain on the economy: due to the ageing of European societies, pension systems are already unsustainable in many EU countries, and the issue would be only aggravated by mass early retirement.[24] On the contrary, studies suggest that the majority of the skill characteristics of jobs in brown sectors could be transferred to green sector jobs:[25] therefore reskilled workers could reintegrate into the workforce relatively easily.

To be sure, the creation of training programmes will incur costs. The EU Skills Agenda, however, already outlines several funding opportunities.[26] Next Generation EU, the Recovery and Resilience Facility, the European Social Fund Plus, Erasmus+, as well as the European Regional Development Fund can support new measures for up- and reskilling programmes. Furthermore, the savings achieved through reskilling rather than relying heavily on early retirement could free up new funds previously allocated to pension systems, which could be redirected towards funding skill programmes as well.

The manifold benefits of reskilling and upskilling

Our proposal aims to prevent political backlash against the green transition by ensuring a smooth and fair transition towards a green economy. Without policies to provide the working-age population with reskilling and upskilling training programmes, disruptions in the labour market, labour shortages in certain sectors and rising unemployment can be expected. These outcomes, in turn, would lead many citizens to lose trust in institutions and turn against the green transition.[27]

The up- and reskilling programmes outlined here would instead help displaced workers from brown industries reintegrate into the labour market. Through a Green Energy Erasmus Programme and inclusive training programmes targeting women, low-skilled and older workers, we would allow the most affected segments of the population to find employment in emerging sectors. This would serve the twin objectives of strengthening the EU’s economy, preventing political backlash against the green transition and propelling the green transition forward.

Marion Beaulieu is a Master student in European Affairs, specialised in Energy, Environment and Sustainability at Sciences Po Paris. Sára Kende is a Master student in a double degree between Sciences Po Paris (European Affairs, specialised in Energy, Environment and Sustainability) and Bocconi University (Politics and Policy Analysis).

This commentary is an updated version of the winning brief from the futurEU Competition 2024, hosted by the futurEU Initiative at the Hertie School and supported by the CIVICA Alliance.

[1] Anneleen Vandeplas et al., “The Possible Implications of the Green Transition for the EU Labour Market”, in European Economy Discussion Papers, No. 176 (December 2022), p. 15, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/583043.

[2] Bertrand Piccard and Maroš Šefčovič, “Green Jobs and the Green Transition: A Long, Bumpy but Exciting Journey”, in Euractiv, 17 November 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/?p=1674933.

[3] Oya Celasun et al., “Cars and the Green Transition: Challenges and Opportunities for European Workers”, in IMF Working Papers, No. 2023/116 (June 2023), https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2023/06/02/Cars-and-the-Green-Transition-Challenges-and-Opportunities-for-European-Workers-534091.

[4] European Commission, Special Eurobarometer 527: Fairness Perceptions of the Green Transition. Report, 2022, p. 27, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2672.

[5] European Commission, European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience (COM/2020/274), 1 July 2020, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52020DC0274.

[6] European Parliament, Report on the Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council on a European Year of Skills 2023, 9 February 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2023-0028_EN.html.

[7] Sofia Fernandes, “A Social Pact for the Energy Transition”, in Thomas Pellerin-Carlin et al., Making the Energy Transition a European Success, Jacques Delors Institute Reports, September 2017, p. 148-211, https://institutdelors.eu/en/publications/making-the-energy-transition-a-european-success.

[8] Javier Sanchez-Reaza et al., Making the European Green Deal Work for People. The Role of Human Development in the Green Transition, Washington, World Bank, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/39729.

[9] Council of the European Union, Council Recommendation of 24 November 2020 on Vocational Education and Training (VET) for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:32020H1202(1).

[10] Javier Sanchez-Reaza et al., Making the European Green Deal Work for People, cit., p. 63.

[11] Veronica Vecchi, “Introduction”, in European Training Foundation, Public-Private Partnerships for Skills Development: A Governance Perspective. Volume I: Thematic Overview, Publications Office of the EU, 2020, p. 9, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2816/422369.

[12] Barbara Janta, Eliza Kritikos and Thibault Clack, “The Green Transition in the Labour Market: How to Ensure Equal Access to Green Skills across Education and Training Systems”, in EENEE Analytical Reports, No. AR02/2022, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/563345.

[13] European Commission, Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2023, Publications Office of the EU, July 2023, p. 54, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/089698.

[14] Anneleen Vandeplas et al., “The Possible Implications of the Green Transition for the EU Labour Market”, cit., p. 19-20.

[15] Javier Sanchez-Reaza et al., Making the European Green Deal Work for People, cit., p. 115.

[16] Aliki Georgakaki et al., “Clean Energy Technology Observatory: Overall Strategic Analysis of Clean Energy Technology in the European Union. 2023 Status Report”, in JRC Technical Reports, 2023, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/150096.

[17] Jannik Jansen, “When Europe Talks Climate, It Needs to Think Jobs”, in Hertie School Policy Briefs, 6 December 2023, https://www.delorscentre.eu/en/publications/skilled-workers-in-the-green-transition.

[18] Will McDowall et al., “Mapping Regional Vulnerability in Europe’s Energy Transition: Development and Application of an Indicator to Assess Declining Employment in Four Carbon-Intensive Industries”, in Climatic Change, Vol. 176, No. 2 (February 2023), Article 7, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03478-w.

[19] Ibid.

[20] RWE, RWE and PPC to Build Solar Projects with More than 200 Megawatts in Greece, 26 January 2023, https://www.rwe.com/en/press/rwe-renewables/2023-01-26-rwe-and-ppc-to-build-solar-projects-with-more-than-200-megawatts-in-greece.

[21] European Commission, Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council on a European Year of Skills 2023 (COM/2022/526), 12 October 2022, p. 18, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=celex:52022PC0526.

[22] OECD, Pensions at a Glance 2023. OECD and G20 Indicators, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1787/678055dd-en.

[23] Anneleen Vandeplas et al., “The Possible Implications of the Green Transition for the EU Labour Market”, cit.

[24] Vincenzo Galasso, “Postponing Retirement: The Political Effect of Aging”, in Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 92, No. 10-11 (October 2008), p. 2157-2169, DOI 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.04.012.

[25] Anneleen Vandeplas et al., “The Possible Implications of the Green Transition for the EU Labour Market”, cit.

[26] European Commission, European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience, cit.

[27] Anneleen Vandeplas et al., “The Possible Implications of the Green Transition for the EU Labour Market”, cit., p. 28.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, giugno 2024, 7 p. -

In:

-

Numero

24|25