Beyond Hydrocarbons: Libya's Blue Gold

Beyond Hydrocarbons: Libya’s Blue Gold

Davide Zurlo*

In today’s Libya, a key resource such as water is exposed to mounting risks due to the ongoing conflict. Like other countries in the Middle East and North Africa – a region which hosts twelve of the world’s most water scarce countries –, Libya suffers from water related challenges, which are only expected to increase in the future due to climate change and urbanisation.

Libya, however, should not be in the position it is today. The country has the potential to become a regional leader in the domain of water, thanks to its extensive underwater reserves. Different aquifers lie beneath Libyan territory, the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (NSAS) being of particular importance as the largest known aquifer in the world.[1]

Extending over an area of about 2 million km² in north-eastern Africa, the NSAS is a transboundary, non-renewable groundwater basin located under the riparian states of Libya, Egypt, Chad and Sudan.[2] A large portion is found in Libya where the aquifer thickness can reach up to 5,000 meters while the total amount of stored water is deemed to be around a half million cubic kilometres.[3]

The importance of groundwater reserves lies on the fact that there are no permanent rivers in Libya and nearly 95 per cent of Libyan territory is desert, with cultivated areas constituting only one per cent of the country.[4] As a result, Libya depends almost entirely on non-renewable, fossil groundwater resources and the NSAS aquifer is therefore of existential importance for the country.

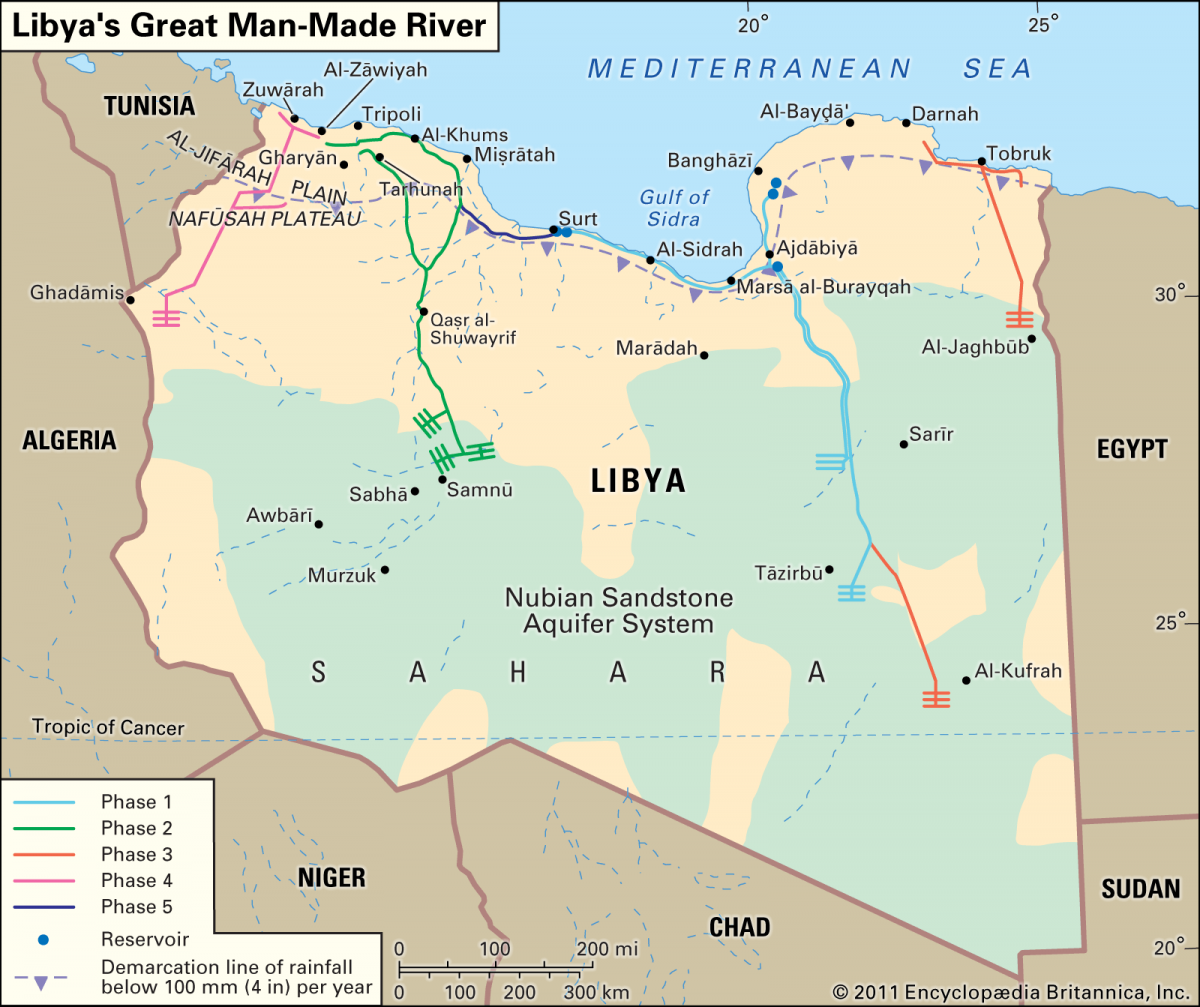

It is in this context that the successful construction and implementation of the Great Man-Made River (GMR) (Figure 1) has been instrumental for Libya’s access to water. First launched in 1983, the GMR project has helped provide free running water to both Libyan coastal cities and agricultural schemes.

Heralded by Muammar Gaddafi as the project that would make the desert as green as the country’s flag, the GMR entailed the construction of more than 1,300 wells (the majority of which over 500 meters deep) and supplied 6,500,000 cubic meters of fresh water per day to the cities of Tripoli, Benghazi, Sirte and other locations.[5] The project cost billions of dollars and was also financed by foreign companies, including Dong Ah (Korean), Nippon Koei (Japanese), Halcrow (UK), SNC-Lavalin (Canadian) and Frankenthal KSB Fluid Systems Consortiums (Germany).[6]

Figure 1 | Illustrative layout of the GMR project

Source: “Libya’s Great Man-Made River”, in Encyclopaedia Britannica, 22 August 2019, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Man-Made-River.

Despite large water resources and massive investments in infrastructure, water supply in Libya has come under increased strain due to the ongoing fighting. Indeed, warring parties are increasingly looking at water as a military tool and target. This started as early as 2011, when during the uprising against Gaddafi, the regime began cutting water supplies to the eastern areas of Libya in order to curb the rebellion.[7] Since the demise of the mercurial dictator, GMR infrastructure has increasingly been targeted by various parties.

Sources from the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) maintain that since the beginning of 2018 there has been a dramatic increase in wells being sabotaged: presently, 96 out of 366 wells feeding the GMR are out of service and the tally continues to mount.[8]

There is now growing concern that western regions are running out of drinkable water. In 2019, the Tripoli-based water authority reported that 101 out of 479 wells belonging to the western supply system had been damaged. Water flow to western Libya decreased from 1.2 million cubic meters a day to about 800,000 cubic meters per day, mainly due to sabotage and inadequacy of funding.[9] A health system crisis is looming in Libya as a result, made all the more worrying given the growing concern for COVID-19 cases registered in the country.

On 6 April 2020, reports surfaced that the water valves of the GMR were shut by an armed group in the southern region of Shwerif, eventually leaving more than 2 million people (including 600,000 children) in the Tripoli area without water.[10] On 13 April, the Shwerif Municipality announced a conditional reopening of the water flow towards Tripoli.[11]

Independently from the motivations for the closure, with some pointing to internal tribal and financial motivations and others linking the action to the ongoing civil war, the incident demonstrates how the absence of a centralised authority has allowed disparate actors to exploit natural resources, from oil to water, for their own narrow purposes, independently from the impact on ordinary Libyans.

Escalating military clashes are also undermining the Libyan response to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic. As noted by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Libyan hospitals and medical facilities are overwhelmed with conflict injuries while doctors who need to be trained on COVID-19 infection prevention protocols “keep being called back to the frontlines to treat the injured”.[12]

Though marred by the current conflict and internal fragmentation, Libya’s future economic development will depend on the equitable access and distribution of natural resources. While oil and energy have tended to dominate international headlines, Libya’s blue gold should not be overlooked, not least given the present COVID-19 crisis.

It may seem hard to believe today, but back in 2011 Libya’s water resources were described as sufficient to start an agribusiness sector similar in scale to that of California’s San Joaquin Valley. Israel and Egypt would represent the only agri-business competitors in the southern Mediterranean region but Libya could surpass both if its extensive water resources were managed correctly.[13]

On 24 February, the European Union signed a partnership with the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation (AICS), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in order to deliver essential health supplies as well as water pumps to help around 30,000 people, including 6,000 children.[14] Similar efforts should also be directed at ensuring that Libyan municipalities, particularly in the disadvantaged south, receive their fair share of resources and developmental investments, helping to build trust but also joint political will for Libya’s future.

International actors need to develop a strategy which tackles Libya’s blue gold as a key resource for stabilisation and sustainability. Unlike oil, which is more politicised and financially valuable, water is an indispensable resource for all and may even become a source of national pride for Libyans’ if managed correctly. As a public commodity, it could help transcend political, regional and tribal fragmentation and plan for a post-conflict economy, serving as a tool for reconciliation to the extent to which it provides incentives to all sides to share Libya’s wealth.

Without political stability it will be hard to intervene and improve Libya’s water sector, let alone plan for a post-conflict economy. With clashes ongoing and international diplomatic efforts to impose a cease-fire faltering, a focus on water as a potential engine for Libya’s post-conflict economy may appear premature. Yet, given the important role of municipalities for the functioning of Libya’s water network, including the GMR, a focus on water may provide a means for international actors to broaden their political engagement with Libyan actors, increasing ownership and engagement at the local levels in Libya.

International actors like the UN, the EU, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, among others, need to act in concert with Libyan authorities at multiple levels to set the country on more sustainable course for the future. Ending the conflict remains a priority, but ensuring that natural resources, from oil to water, does not further become a military tool to strengthen one side over the other is of no less importance, not least since concerted action on these dossiers may also help de-escalate the fighting.

Increased engagement with regional states, should also be pursued, beginning from Libya’s neighbours but also extending to the African Union. Water is an essential resource for Libya and the wider region and the NSAS aquifer is shared with other regional states. Feasibility studies for regional exploitative mechanisms could be pursued by international consortiums, providing incentives to regional governments to increase diplomatic action to end the fighting and pursue more cooperative neighbourly relations.

The present COVID-19 crisis and calls for global ceasefires in conflict zones may represent an opportunity for international actors, beginning from the EU, to compel regional and international states to halt their military support and prevent a wider humanitarian crisis in the country and region. Water will be essential to counteract the spread of the pandemic, providing an opportunity to refocus attention on Libya’s blue gold, fully integrating the management of this most important resource into international diplomatic efforts to support a serious and inclusive political settlement in Libya.

* Davide Zurlo, studied Arabic and Hebrew in Venice and holds an MA in International Relations from the University of Kent. An alumnus from the College of Europe, he specialises in International Relations of the Middle East and North Africa.

[1] FAO, AQUASTAT Country Profile - Libya, 2016, http://www.fao.org/3/i9803en/I9803EN.pdf.

[2] Setta Tutundjan, Regional Consultation Report. Groundwater Governance Project Third Regional Consultation: Arab States Region, Amman, 8-12 October 2012, p. 14, http://www.groundwatergovernance.org/fileadmin/user_upload/groundwatergovernance/docs/Amman/GWG_arab_consul_finalreport.pdf.

[3] Ahmed R. Khater et al., “Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (NSAS) M&E Rapid Assessment Report”, in Monitoring and Evaluation for Water in North Africa (MEWINA) Project Reports, May 2014, p. 12, http://web.cedare.org/?p=2467.

[4] FAO, AQUASTAT Country Profile - Libya, cit., p. 1.

[5] Tamar Melike Tegün, “Saving Lives with a Great Man-Made River”, in Interesting Engineering, 6 September 2016, https://interestingengineering.com/saving-lives-great-man-made-river.

[6] More information regarding the contractors and sub-contractors which took part to the various phases of the project can be found in Water Technology website: GMR (Great Man-Made River) Water Supply Project, https://www.water-technology.net/?p=1661.

[7] Logman Hammam, “The Water Problem in Libya Is Surfacing” (video in Arabic), in Al Jazeera, 15 July 2011, https://youtu.be/lpDHLfrYmHM.

[8] UNSMIL, UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Libya Strongly Condemns the Blockage of the Great Man-Made River, Cutting Off Water Supply for Hundreds of Thousands of Libyans, 20 May 2019, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/node/100042301.

[9] Ulf Laessing and Ahmed Elumami, “In Battle for Libya’s Oil, Water Becomes a Casualty”, in Reuters, 2 July 2019, https://reut.rs/2xqEOdA.

[10] UNSMIL, Statement by Yacoub El Hillo, Humanitarian Coordinator in Libya, on the Disruption of Water and Electricity Supply, 10 April 2020, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/node/100042528.

[11] See, “Al-Shweref Municipality Announces Conditional Allowance for the Return of the Flow of Artificial River Water to the Capital, Tripoli” (in Arabic), in Al-Wasat, 13 April 2020, http://alwasat.ly/news/libya/279901.

[12] ICRC, Libya: People Caught Between Bullets, Bombs and COVID-19, 12 April 2020, https://www.icrc.org/en/node/77835.

[13] Simba Russeau, “Libya: Water Emerges As Hidden Weapon”, in The Guardian, 27 May 2011, https://gu.com/p/2pd2c.

[14] European External Action Service (EEAS), European Union Partnership with AICS, UNDP and UNICEF: For Better Access to Services in Libya, 25 February 2020, https://europa.eu/!qh78GG.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, aprile 2020, 5 p. -

In:

-

Numero

20|28