The Emergence of a European Political Space

The Emergence of a European Political Space

Stefan Lehne*

When citizens vote in the European Parliament elections in May, the exercise will yet again boil down to 27 parallel national elections. The 705 members will be elected according to national lists and national electoral laws, after campaigns organised by national parties.

Certainly, there will be Europe-wide lead candidates (Spitzenkandidaten) from some of the main EU party groups. Yet, as in the last elections in 2014, they are unlikely to get much traction, as most national parties ultimately see the contest as a domestic trial of strength.

This is one of the paradoxes of EU politics. Political elites in member states have been very generous in providing the European Parliament with expansive legislative and budgetary powers, turning it into the most powerful transnational assembly in the world. Yet, they have also been extremely restrictive when it comes to allowing space for a genuinely European electoral process to take shape.

There have been several initiatives to introduce transnational lists, whereby seats would be reserved for a special electoral district covering all of the EU. This would enable, for example, a Portuguese citizen to vote for a Finnish candidate, and would thus reduce the control of national parties over the elections. So far, however, the majority of the latter do not wish to create a parallel European political space and have blocked these initiatives repeatedly.[1]

Nonetheless, a European political space is gradually opening up. This is due to two interrelated developments: the “nationalisation” of European politics and the “Europeanisation” of national politics.

The nationalisation of European politics

Throughout the EU’s existence, all of its political institutions have been governed by an informal coalition of mainstream parties from the centre-right and centre-left. The great majority of members of the European Council and the European Commission came from these parties, as did a majority of the members of the European Parliament.[2]

All of the EU’s leadership positions have been in the hands of the right-wing European People’s Party (EPP) group and the left-wing Socialists and Democrats (S&D), whose summits ahead of every Council meeting have become the EU’s main political consultation fora.

On substantive issues, the European Parliament does not have a system of party discipline similar to the ones at the national level. Parliamentarians vote according to their personal ideological inclinations, in line with their parties, or according to their respective national interests. Diverse coalitions form depending on the subject at hand.

Still, the EPP and the S&D have essentially been running the parliament by holding the most important committee chairs and reporting roles, setting the rules and the political agenda.

This centre-right and centre-left co-dominion may appear stifling, particularly to those members of the European Parliament who do not belong to either of these two political families. However, it has provided stability in situations of crisis, ensured continuity across electoral cycles, and insulated the EU from the vagaries of national politics.

In recent years, the political landscape in many member states has started to fragment, however. Traditional mainstream parties are losing ground. Far-right and far-left forces are gaining strength, but so have new players from the centre, like Emmanuel Macron’s movement in France or the Greens in Germany, which have made dramatic gains.

Already in 2014, the European Parliament elections saw a massive influx of anti-establishment members.[3] About a quarter of current members hold distinctly Eurosceptical views. Yet, since mainstream parties had won a comfortable majority and the populists were divided among competing party groups, the overall power constellation did not change significantly.

The current institutional cycle of the EU has thus been marked by the customary dominance of the EPP and S&D. Yet, this period seems to be coming to an end now.

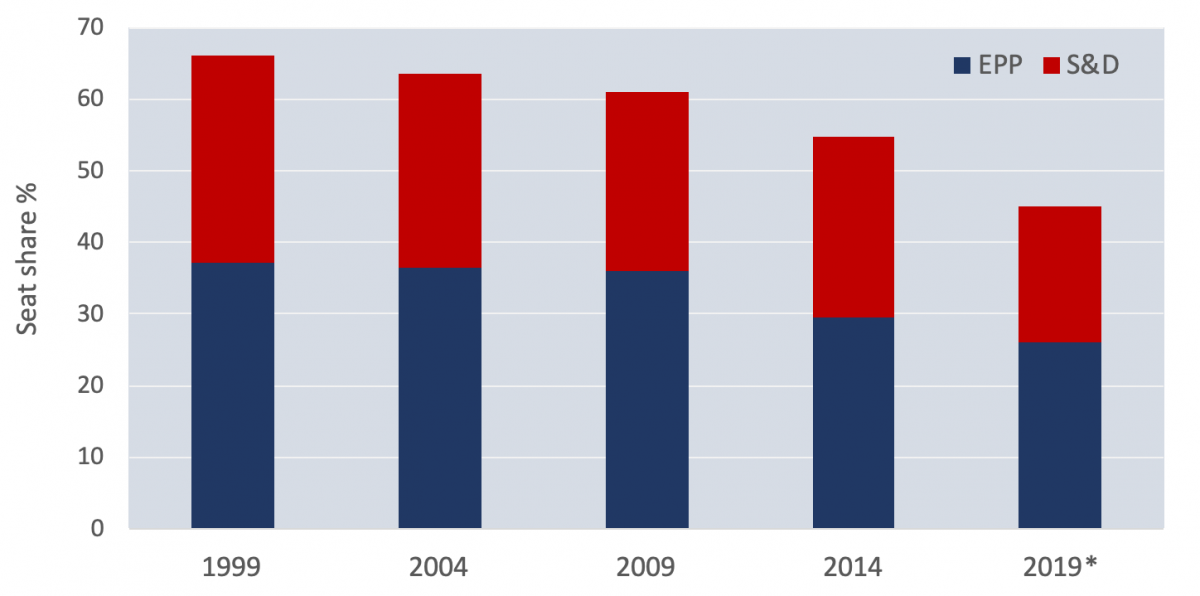

Figure 1 | EPP and S&D European parliament election results

Note: * European Parliament poll February 2019.

Source: Author’s elaboration on data retrieved from the European Parliament website: Previous European Parliamentary Elections; Kantar Public, European Elections 2019. Report on the Developments in the Political Landscape, Brussels, 28 February 2019.

According to most polls, the EPP and S&D will no longer have an absolute majority in the next European Parliament.[4] For the first time, they will need to form a coalition with other parties. This is likely to have a big impact on the political dynamics in the parliament as well as on the decisions pertaining to the next leaders of EU institutions.

Party affiliation counts for less in the European Council, the central decision-making body of the EU. Yet, its political composition also looks very different from just a few years ago. The EPP currently has nine members, only one more than the Liberals (though these mostly come from smaller states), while the S&D has five members.

As cracks emerge in the traditional duopolistic system, EU institutions are beginning to look increasingly like their counterparts in most member states, with a plurality of diverse actors involved in complex coalition building. Politics is interfering more and more with the traditional method of preparing EU decisions through a long process of technocratic discussions outside the public sphere.

Increased volatility at the national level is also impacting the European scene. A few years ago, discussing national politics in Brussels was often frowned upon. Nowadays, national dynamics form an important part of the daily discourse.

National political developments affect the EU’s work more than ever. The Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, the 2016 presidential election in France, and the parliamentary elections in Italy in 2018 demonstrated that changes of the composition and the orientation of national political leadership can rapidly reshape the constellation of forces at the EU level.

The presence of Eurosceptic parties in some national governments has reduced the common political ground among member states and opened up new divisions. Long delays in forming governments and coalition crises can also seriously disrupt the EU’s agenda.

The Europeanisation of national politics

It is not just national politics that matter more and more at the EU level – a reverse process is also taking place in parallel across domestic contexts.

The EU was founded as a top-down project at a time when citizens seemed readier than they are today to trust the wisdom of political elites. However, this “permissive consensus” was already fading in the early 1990s. The more the EU entered into sensitive policy areas, such as border control or monetary policy, the more citizens’ discontent became evident, with new treaties being rejected in Denmark in 1992, in France and the Netherlands in 2005, and in Ireland in 2001 and 2007.

Despite these setbacks, the EU continued to evolve. Modifying the treaties, the union’s customary method of reforming itself, became increasingly difficult, however. In today’s increasingly divided EU, member states find it hard to agree on any comprehensive reform project. And, even if they did, the likelihood of numerous popular referenda to approve the reforms would make ratification highly uncertain.

The financial crisis drove the politicisation of the EU to new levels. Large parts of the population in southern member states resented the austerity policies imposed by Brussels while many in northern ones complained about the use of taxpayer money for bailing out struggling economies.

The political salience of EU action also increased as a result of the new rules on budgetary discipline adopted during the crisis. Some politicians present the European Commission examining national budgets as an interference in areas that used to be reserved for the nation state, such as education, health, and pensions.

The refugee crisis of 2015–16 triggered widespread concerns about security and the loss of control over external borders, raising the political temperature further. In the absence of an effective EU-level response early in the crisis, calls grew to take back control over key issues.

Eventually, as national parties and political movements from the far-right to the left mobilised against international agreements such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership with the United States or the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with Canada, even trade policy, long seen as the European Commission’s ultimate technocratic instrument, was affected by the politicisation of EU actions.

This growing intrusion of EU issues into domestic political debates had an impact on national political trends, resulting in the rise of anti-establishment and Eurosceptic movements accusing the EU of undermining national sovereignty. In response, mainstream politicians were forced to articulate their positions on EU policies more clearly and actively than before.

EU policies now constantly feature in domestic political debates in member states. Will this eventually lead to a realignment of political parties along a pro/anti-integration axis or will alternative alignments emerge after a period of trial and error?

While it is still too early to tell, should current trends continue, national politics might eventually be marked by the same dual polarisation between right and left and pro- and anti-EU positions that has long been a characteristic of the European Parliament.

Conclusion

There used to be a sphere of national politics with ongoing competition between ideologically diverse political parties focused on domestic concerns, with intermittent changes of government and direction, and a political discourse full of polemic and passion.

There used to be a quite different sphere of EU politics where a grand centrist coalition ruled permanently, and political issues were submitted to long technocratic negotiations resulting in complex compromises without clear winners and losers.

Today the divide between these two spheres is breaking down and each is beginning to resemble the other. EU institutions experience more divisive debates. Decision-making now requires variable coalition building and politics replaces the traditional technocratic approach.

Conversely, national politics is increasingly focused on EU issues and the rivalry between pro- and anti-EU political forces is turning into an important feature of national debates.

As national and EU politics gets more and more intertwined, the dividing line between the two spheres is fading away and a common European political space begins to slowly take shape.

Paradoxically, the mobilisation of the nationalist right might give the current campaign for the European Parliament elections a stronger transnational character than earlier ones. Macron has recently embraced this challenge by framing his party’s electoral manifesto as a letter to all European citizens.[5]

There are many constraints on the development of a European political space, such as language barriers and the fragmentation of most media along national lines. What is more, it is still too early to grasp the full consequences of this development. The increasing volatility of national politics could complicate EU decision-making and make blockages more likely, but it could also introduce fresh ideas and alignments to European politics.

The prominence of EU issues in national debates could bring about an eventual convergence of political cultures across member states, but it could also at times result in nasty nationalist backlashes.

It seems safe to say, however, that at a time when the constitutional route toward full political union appears blocked, practical politics at EU and national level are becoming more and more integrated. This is likely to profoundly influence the future of the European integration.

* Stefan Lehne is a visiting scholar at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, where his research focuses on the post–Lisbon Treaty development of the European Union’s foreign policy, with a specific focus on relations between the EU and member states.

This article is the second in a number of IAI Commentaries published in the framework of the Mercator European Dialogue project, run by the German Marshall Fund (GMF), the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI), the Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP) and the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB).

[1] Christine Verger, “Transnational Lists: A Political Opportunity for Europe with Obstacles to Overcome”, in Jacques Delors Institute Policy Papers, No. 216 (7 February 2018), http://institutdelors.eu/?p=27411.

[2] Martin Westlake, “Possible Future European Union Party-Political Systems”, in Bruges Political Research Papers, No. 60 (October 2017), https://www.coleurope.eu/node/41009.

[3] Peter Spiegel and Hugh Carnegy, “Anti-EU Parties Celebrate Election Success”, in Financial Times, 26 May 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/783e39b4-e4af-11e3-9b2b-00144feabdc0.

[4] Europe Elects offers an overview over the current polling for the 2019 elections: https://europeelects.eu.

[5] Emmanuel Macron, “Dear Europe, Brexit Is a Lesson for All of Us: It’s Time for Renewal”, in The Guardian, 4 March 2019, https://gu.com/p/aqman.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, aprile 2019, 6 p. -

In:

-

Numero

19|29

Tema

Tag

Contenuti collegati

-

Ricerca21/05/2015

Open European Dialogue (già Mercator European Dialogue)

leggi tutto