The EU and Ukraine’s Public Opinion: Changing Dynamic

Introduction: The West appreciated Ukraine’s pluralism by default

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian society and political establishment chose a different path of transformation than Russia. Ukraine gained its independence peacefully and without internal conflicts thanks to an agreement between the national-democratic opposition and the so called “national-communists”. The West appreciated the facts that 1) Ukraine was the first state from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) to re-elect both president and parliament in the 1994 democratic elections; 2) in contrast to Russia’s 1993 constitution, which established a model of creeping authoritarianism in that it placed massive authority on the president, Ukraine’s 1996 constitution was a compromise between the president and parliament; 3) again in contrast to Russia, political opposition in Ukraine was much stronger. In fact, only one president, Leonid Kuchma (1994–2004) was reelected. The rest, except fugitive Viktor Yanukovych (2010–2014), lost elections to their opposition rivals. In parliamentary elections opposition parties defeated ruling rivals in 2006, 2007 and 2019. All Ukrainian governments also had to take the interests of the country’s different regions into account. Thus, this system was much more balanced than the Russian model. From the point of view of Western political science, “pluralism by default” emerged in Ukraine, i.e. unplanned and unintentional pluralism.[1]

Before 2014: Ukrainians in favour of the EU but against NATO

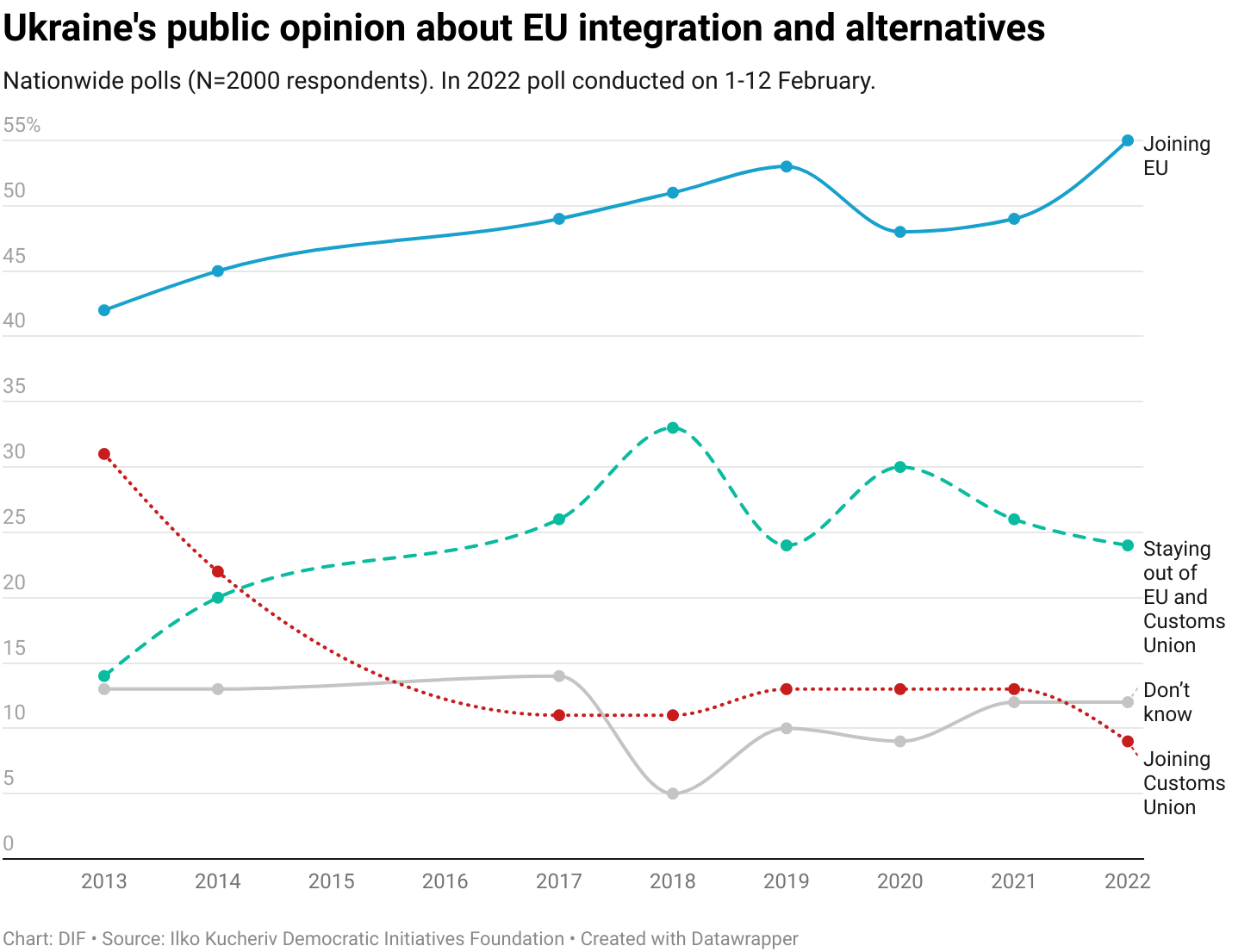

Even before the 2013–2014 EuroMaidan pro-EU protests that precipitated Russia’s first invasion of Ukraine, majority of Ukrainians believed that the future of their country should be within the EU.[2] According to a 2012 poll, 46 per cent of Ukrainians supported the view that Ukraine should become an EU member while 33 per cent rejected the idea. It is noteworthy that even in the Donbas region and Crimea, people aged 18–29 did not differ from their peers who lived in other parts of the country. Data showed that 51 per cent of the youth in the eastern part of the country were in favour of Ukraine’s membership in the EU, while only 22 per cent were against. Besides, the attitude toward EU membership depended on the level of people’s awareness. The poll showed that 52 per cent of Ukrainians who were well-informed about the talks between Ukraine and EU on the Association Agreement were in favour of membership.

Pro-European views increased after EuroMaidan and the first Russian invasion. The number of supporters of EU integration increased from 47 per cent in December 2013 to 57 per cent in December 2014, while the share of proponents of integration into the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan dropped from 26 per cent to 16 per cent in the same period.[3] These sentiments remained unchanged despite the total overhaul of the government (president and parliament) in 2019. After one year of presidency of Volodymyr Zelenskyy, 48 per cent of Ukrainians believed that integration with the EU was the best policy option for Ukraine, while support for the Customs Union with Russia fell to 11 per cent.[4]

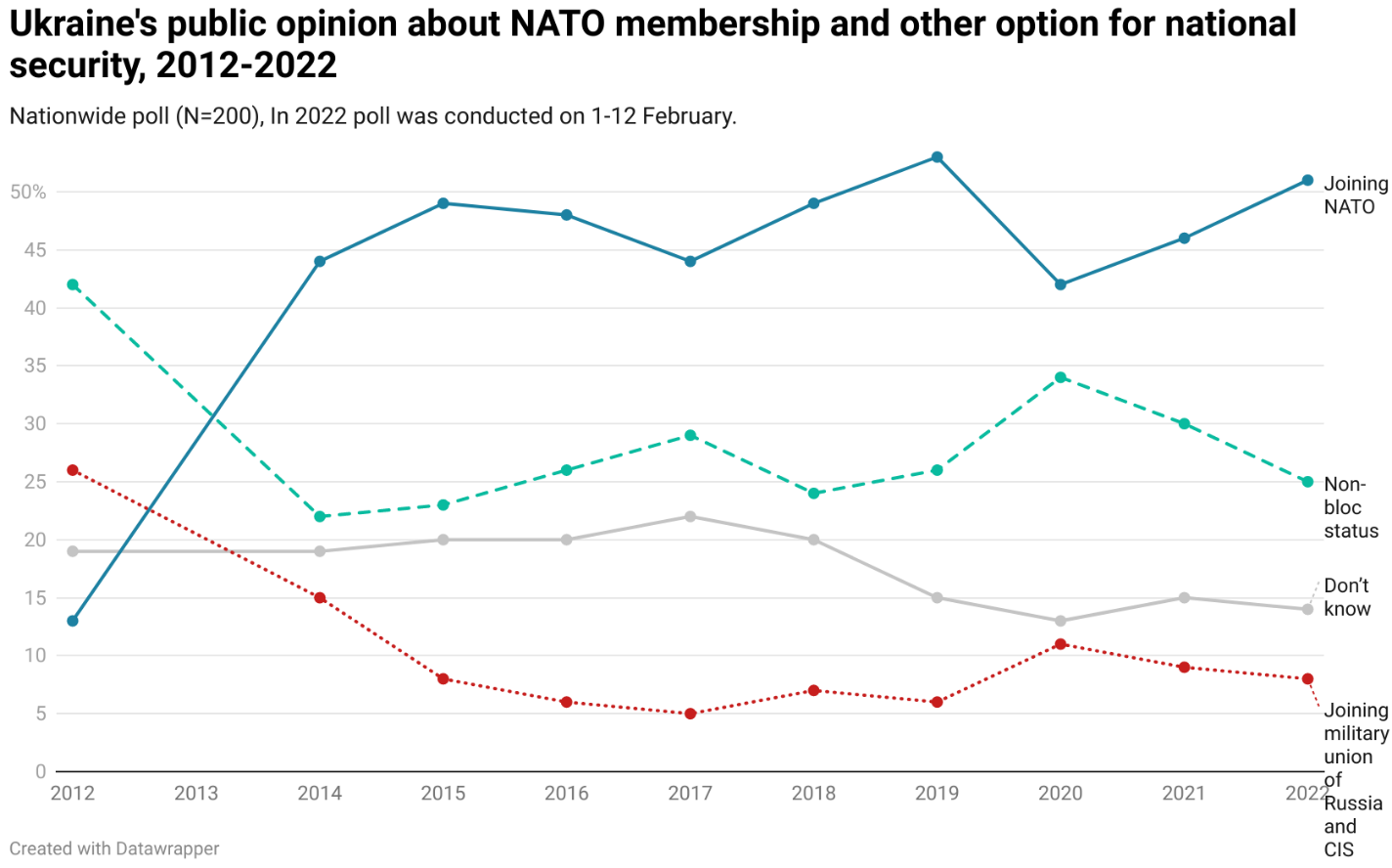

Attitudes toward membership in NATO followed a different pattern. Until 2014 NATO was not popular in Ukraine. Just before the Bucharest NATO summit, when the Alliance first made a promise of membership to Ukraine, an April 2008 poll of the Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DIF) showed that only 22 per cent of Ukrainians supported it. NATO supporters were in the minority even in the traditionally nationalist western Ukraine and Kyiv.[5] Moreover, mainstream political process and media influenced and shaped attitudes toward NATO. Two years of presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, who used pro-Russian rhetoric, flirted with pro-Russian media and constituents, resulted in a decline of support for Ukraine’s integration into NATO. In April 2012 the number of NATO proponents fell to just 13 per cent. Support for the NATO integration decreased across the country: 38 per cent in Western Ukraine, 14 per cent in Central Ukraine, 6 per cent in the south and 1 per cent in the east.[6]

EU ambiguity in the first phase of the Russia’s aggression (2014–2022)

Before EuroMaidan, most American and European policy-makers and scholars looked at Ukraine through the lenses of its superficial similarities with Russia rather than its important differences from it. The Soviet legacy, common history and post-Soviet practices, especially weak institutions, endemic corruption and informal politics overshadowed the growing role of civil society and the strengthening of the national identity of the Ukrainians. As a result, Ukraine was depicted as “grey zone”[7] or Russian vassal state.[8]

But even after EuroMaidan, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, intrusions into the Donbas and hybrid aggression against Ukraine, EU institutions and most member states continued to treat Ukraine only as a Russia’s neighbouring state, which must find solution for its security and economic troubles, caused by Russia, through negotiations and with respect to the interests of the troublemaker. Such treatment made Ukrainian leaders cautious toward Western policies and intentions, although the path to full membership in EU and NATO was still considered the main tool for strengthening the nation’s security and sovereignty.[9]

It was remarkable to observe how EU policy toward Ukraine, especially in the highly important and sensitive topic of resolution of conflict in Donbas, was detached from reality and ignorant of Ukrainian public opinion.

The EU missed the point when it hoped that Ukraine and Russia (both states and societies) could find ways for reconciliation. Russian military aggression against Ukraine in 2014 became the determining factor in the rapid decline in the percentage of Ukrainian citizens in all regions of Ukraine positively inclined toward Russia. In 2016, only 10 per cent of Ukrainians believed in the possibility of normalisation of bilateral relations between Ukraine and Russia in the near future. Meanwhile, nearly half of the population of Ukraine (49 per cent) felt that normalisation of relations could only happen in the distant future and nearly one fourth of Ukrainian citizens (24 per cent) did not believe in such prospect at all.[10]

Furthermore, as Russia continued its aggressive steps toward Ukraine, like the complete closure of the Sea of Azov (2018), the distribution of the Russian passports to the people who lived in the occupied areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and open threats of invasion (2021), Ukrainians were becoming more and more determined to withstand Russian pressure with force. In May 2021, 71 per cent of Ukrainians believed that Ukraine and Russia were at war with each other. Majority of Ukrainians (53.5 per cent) defined the Donbas armed conflict as “Russian aggression with the use of local proxies against Ukraine” while 62 per cent of respondents thought that peace in Donbas cannot be achieved because of Russian government’s unwillingness to cooperation with Ukraine.[11]

Russian aggression in the Donbas and open threats of invasion, in fact, led to a strengthening of the unity of the Ukrainian polity, which was coalescing and developing since 1991 and gained a new resoluteness during Euromaidan. Ukrainians have determined for themselves who they are in a geopolitical sense and want their country to be a member of the EU and NATO.[12]

In February 2022, despite the growing threat of invasion, 43 per cent of Ukrainians were against any concessions to Russia, even if the Kremlin had promised to stop its aggression. The same poll also showed that many, though not all, Ukrainians were ready to fight. The number of those willing to join the volunteer forces to counter military aggression by Russia in the case of a new invasion of Ukraine increased to 14 per cent. Another 8 per cent were ready to defend Ukraine in the armed forces, 25 per cent would provide as much non-military assistance as they could. Thus, almost half (48 per cent) would either fight or assist the army against a much stronger enemy, which is a historically high figure (not just for Ukraine but in general).[13]

Yet, most EU capitals believed that in case of full-scale Russia’s invasion Ukraine would collapse in a week or so and they were quite surprised by successful resistance of Ukrainians.

After 24 February 2022: Unanimous support for the EU and NATO

The full-scale invasion sealed Ukraine’s complete break-up with Russia and with everything that the Russian president values as “foundations” of his regime and Russian society: myth of great common Soviet past, greatness of the Russian culture and unique role of the Russian language in the post-Soviet space, “brotherhood” and unity of the Eastern Slavic nations, superiority of the Russian Orthodox faith and “special mission” of Russia in the global affairs.

First, successful nationwide grassroot resistance against authoritarian Russia has increased support for democracy amongst Ukrainians. By August 2022, 64 per cent of respondents believed that democracy is the most preferable form of government while only 14 per cent agreed that autocracy could be “in some cases” better than democracy, and another 13 per cent said they did not care about any type of regime. These rates of support for democracy are the highest in many years of observation: in 2014 less than 50 per cent supported giving priority to democracy; after the Revolution of Dignity (EuroMaidan) this rate rose to 54 per cent, but only after the outbreak of the full-scale war did it exceed 60 per cent. Also, in August 2022, more than 47 per cent were ready to suffer economic difficulties for the sake of freedom and guarantees of all civil rights while only 31 per cent of respondents could agree to give away some freedoms to receive better public welfare.[14] Therefore, despite the inevitable concentration of power during the wartime martial law in Ukraine, there is a widespread belief among Ukrainian experts that there will be no monopolisation of power. The EU candidate status received by Ukraine in June 2022 has strengthened this view. The candidacy is viewed as a powerful tool for domestic transformation.

Second, Ukrainians have become more united in terms of goals in war and post-war arrangements. There were hopes among Western ‘Putin-understanders’ that Ukrainians would tire of war and decide to make concessions to stop it. Also, there were concerns among foreign policy experts that sufferings and atrocities might weaken Ukrainian determination to continue the war until all occupied territories are liberated. However, according to the same August 2022 poll, more than 90 per cent of respondents believed that Ukraine would win the war (77 per cent do believe and 15 per cent rather believe). The majority of respondents (55 per cent) said that the withdrawal of Russian troops from the entire territory of Ukraine and the restoration of borders as of January 2014 can be considered a victory. Another 20.5 per cent were even more radical – a victory in the war for them would be the destruction of the Russian army and the assistance to the breakdown of Russia. Only small per cent of Ukrainians considered the possibility of ceding Crimea (9 per cent), Crimea and Donbas (7.5 per cent) or areas captured by Russia since February (3 per cent). After the war, more than 75 per cent of respondents would support the decision to completely severe relations with Russia and even introduce complete ban on the entry of Russians into Ukraine.[15]

Third, the war caused tremendous changes in historical memory and in the field of de-Communistisation. In these areas, the views of Russians and Ukrainians diverge more and more. Already in May 2021 62 per cent of Ukrainians (and the majority in all regions) had a negative view of Stalin’s role in relation to Ukraine. 48 per cent of Ukrainians supported the view that World War II arose as a result of a secret agreement between Hitler and Stalin on the division of spheres of influence in Europe (29 per cent disagree, another 23 per cent are undecided.[16] This is in sharp contrast to Russia, where this topic is banned for public discussion.

Russia’s full-scale aggression has only widened the gap. In the August 2022 poll, 67 per cent of the respondents positively assessed the disintegration of the Soviet Union (negatively only 16 per cent). 59 per cent of Ukrainians supported the decision to condemn the USSR as a communist totalitarian regime. Only 13 per cent of respondents disagreed.[17] This is a huge change since 2020, when only 49 per cent of Ukrainians considered collapse of the USSR as positive event and 34 per cent supported condemnation of the Soviet regime.

All these changes helped Europeans to better understand Ukraine and its desire to integrate into Europe. Support, though belated, given to Ukraine from countries which previously were reluctant to provide military assistance (the most important among them are Germany, France and Italy), improved their standing in Ukraine. As a result, Ukrainians’ support for joining the EU registered a record of 86 per cent and 83 per cent for NATO.[18]

Ukraine’s successful counteroffensives in Kharkiv and Kherson regions as well as Russia’s massive attacks against civilians and energy infrastructures have further strengthened Ukrainians’ resolve to keep fighting. According to nationwide poll, conducted from 21 to 27 October 2022, the number of Ukrainians who expressed willingness to fight or support the army increased to 59 per cent. Only 5 per cent of the polled said that any compromise with Russia is acceptable for the sake of peace, while 66 per cent said that the war can end only in case of victory, and only 17 per cent thought that compromises can be achieved but not on everything.[19]

Ukrainians are aware that national survival and victory depends on Western support. In August 2022, 63 per cent of respondents agreed with statement that Ukraine could survive only if the West provides economic aid and 74 per cent agreed that Ukraine could survive only if the West provides military aid.[20]

It is necessary to point out that the opinion of Ukrainians about the crucial role of the external assistance provided by NATO does not differ from opinion of other Central European nations. For instance, a GLOBSEC poll conducted in March 2022 showed that 88 per cent of Poles, 79 per cent of Latvians and Czechs, 75 per cent of Hungarians and 74 per cent of Lithuanians, 70 per cent of Estonians, 62 per cent of Romanians and Slovaks agreed with the statement that NATO membership was the most important national deterrence asset.[21] Finland and Sweden acted on the same assumption when they decided to abandon their long-standing neutrality policy and applied for NATO membership earlier this year.

The amount of support by EU and NATO countries proves that Ukraine’s successful resistance against Russia is a key security objective for the whole Euro-Atlantic community. Western assistance is indeed necessary for Ukraine to achieve victory, but for any peace to be sustainable after the war ends Ukraine shall need to become a member not just of the EU but NATO too.

Olexiy Haran is Professor at National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Petro Burkovskyi is Executive Director of the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DIF).

[1] Olexiy Haran, “Wie hat sich die Ukraine seit der Unabhängigkeit entwickelt?”, in Ukraine-Analysen, No. 255 (28 September 2021), p. 3-5, https://www.laender-analysen.de/ukraine-analysen/255/wie-hat-sich-die-ukraine-seit-der-unabhaengigkeit-entwickelt.

[2] Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation (DIF), Ukrainians Opt for EU Membership, in Particular the Youth, 14 April 2012, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/ukrainians-opt-for-eu-membership-in-particular-the-youth.

[3] DIF, Public Opinion in Ukraine: Results of 2014 [in Ukrainian], 29 December 2014, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/gromadska-dumka-pidsumki-2014-roku.

[4] DIF, What Ukraine and the World Experienced in 2020 and What We Can Expect in 2021: Political And Economic Forecasts [in Ukrainian], 21 December, 2020, https://dif.org.ua/article/shcho-perezhili-ukraina-ta-svit-u-2020-rotsi-y-chogo-nam-chekati-2021-go-politichni-y-ekonomichni-prognozi#_Toc59385791.

[5] DIF, Results of a Nationwide Poll on Ukraine’s Membership in NATO and the EU [in Ukrainian], 2 April 2008, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/rezultati-zagalnonatsionalnogo-sotsiologichnogo-opituvannya-shchodo-chlenstva-ukraini-v-nato-ta-es.

[6] DIF, Ukraine on the Eve of the NATO Summit in Chicago: What We Have and What We Hope For! [in Ukrainian], 17 May 2012, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/ukraina-naperedodni-samitu-nato-v-chikago-shcho-maemo-y-na-shcho-spodivaemos.

[7] Robert Legvold and Celeste A. Wallander (eds), Swords and Sustenance. The Economics of Security in Belarus and Ukraine, Cambridge, MIT Press, 2004.

[8] Victoria Nuland, Ukrainian Reforms Two Years After the Maidan Revolution and the Russian Invasion, Statement before the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Washington, 15 March 2016, https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CHRG-114shrg30526/context.

[9] Petro Burkovskiy and Olexiy Haran, “Ukraine’s Foreign Policy and the Role of the West”, in Daniel S. Hamilton and Stefan Meister (eds), Eastern Voices. Europe’s East Faces and Unsettled West, Washington, Center for Transatlantic Relations, 2017, p. 51-76, https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/publication/eastern-voices-europes-east-faces-unsettled-west.

[10] DIF, Ukraine-Russia: What Should Be the Format of Future Relations?, 17 March 2017, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/ukraine-russia-what-should-be-the-format-of-future-relations.

[11] DIF, War in Donbas and Russian Aggression. How Ukrainian Public Opinion Has Changed After Two Years of Zelenskyi’s Presidency. Key Points and Observations, 9 June 2021, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/War%20in%20Donbas%20and%20Russian%20Aggresssion.%20How%20Ukrainian%20Public%20Opinion%20Has%20Changed%20After%20Two%20Years%20of%20Zelenskyi%27s%20Presidency.%20Key%20points%20and%20observations.

[12] Olexiy Haran and Maksy Yakovlyev (eds), Constructing a Political Nation: Changes in the Attitudes of Ukrainians during the War in the Donbas, Kyiv, Stylos Publishing, 2017, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/constructing-a-political-nation-changes-in-the-attitudes-of-ukrainians-during-the-war-in-the-donbas.

[13] DIF, No to Russia’s Aggression: Public Opinion of Ukrainians in February 2022, 22 February 2022, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/no-to-russias-aggression-the-public-opinion-of-ukrainians-in-february-2022.

[14] DIF, Independence Day of Ukraine: What Unites Ukrainians and How We See Victory in the Sixth Month of War, 24 August 2022, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/independence-day-of-ukraine-what-unites-ukrainians-and-how-we-see-victory-in-the-sixth-month-of-war.

[15] Ibid.

[16] DIF, Victory Day and Its Role in the Historical Memory of Ukrainians: What Meaning Do Citizens Attach to This Date?, 24 May 2021, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/victory-day-and-its-role-in-the-historical-memory-of-ukrainians-what-meaning-do-citizens-attach-to-this-date.

[17] DIF, How the Attitude of Ukrainians to Decommunization, Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and Nationalism Is Transforming amid the Russian War against Ukraine, 24 October 2022, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/how-the-attitude-of-ukrainians-to-decommunization-ukrainian-orthodox-church-moscow-patriarchate-and-nationalism-is-transforming-amid-the-russian-war-against-ukraine.

[18] Rating Group, Foreign Policy Orientations of the Ukrainians in Dynamics (October 1-2, 2022), 3 October 2022, https://ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/dinam_ka_zovn_shno-pol_tichnih_nastro_v_naselennya_1-2_zhovtnya_2022.html.

[19] DIF, Presentation “How Ukrainians See Goals and Exit from War and Why It Is Important for Ukraine’s Partners”, 2 December 2022, https://dif.org.ua/en/article/presentation-how-ukrainians-see-goals-and-exit-from-war-and-why-it-is-important-for-ukraines-partners.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid; GLOBSEC, GLOBSEC Trends 2022. CEE amid the War in Ukraine, Bratislava, May 2022, https://www.globsec.org/node/740.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, dicembre 2022, 10 p. -

In:

-

Numero

JOINT Brief 25