How Italians View Military Spending

On 16 March, a sweeping majority in the Italian Chamber of Deputies approved order 9/3491-A/35 committing the Italian government to raise the defence budget to 2 per cent of GDP.[1] Taken in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this decision strengthens Italy’s adherence to the commitment made by NATO countries in 2004 and reiterated at the 2014 NATO summit in Newport, Wales.

The announcement comes after half a decade of increasing Italian defence spending. Having decreased from 1.5 per cent of GDP in 2010 to 1.2 per cent in 2015, Italy’s military expenditures started to grow again, reaching 1.6 per cent of GDP in 2020. This figure is still considerably lower than the UK’s 2.2 per cent or France’s 2 per cent, but higher than Germany’s and Spain’s 1.4 per cent.[2]

To understand the broader context within which Italy has decided to renew its commitment to the NATO target, Italian public opinion should be factored in. In this respect, opinion polls conducted prior to the war in Ukraine can shed some light on Italian attitudes toward defence spending in general and the 2 per cent NATO pledge specifically.

In a previous article, we analysed Italian public opinion trends about military spending over several decades.[3] On the whole, Italians have never been eager to increase defence expenditures. Based on data from the 1950s to date, on average, less than one-fifth of respondents believe that military spending is too low or should be increased. At the same time, support for increased military spending in Italy has fluctuated over time. Depending on how the question is worded, those favouring greater military spending range from a minimum of 5 per cent to a maximum of 60 per cent.

This variation can be explained by two factors. First, one must consider the – mostly short-term – impact of specific political circumstances. For example, the share of Italians supporting an increase in military spending fell from 12 per cent to 6 per cent between 1988 and 1989, purportedly as a direct result of the end of the Cold War.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, the way the question is worded has a significant influence on the results, a dynamic which in turn can also provide some insights on the underlining rational motivating these opinions. In general terms, Italians appear more likely to agree to increase military spending under the following circumstances: (i) if asked specifically whether they are in favour of increased spending rather than being asked whether they would prefer to raise, lower or leave it unchanged; (ii) if the question refers to “defence budgets” rather than “military spending”; and (iii) if the spending increase takes place in a multilateral context or in pursuit of shared political objectives (for example, increasing European strategic autonomy).

Departing from these general considerations, we also assessed how Italians react to the specific NATO commitment of increasing defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP and how these responses are distributed across the electorate.

Italians are generally sceptical about fulfilling the NATO commitment, as demonstrated by a pan-European survey carried out in October 2020 and again in autumn 2021.[4] In 2020, compared to an EU average of 48 per cent, only 37 per cent of Italians said they strongly or fairly agreed with the statement: “Italy must ensure to spend at least 2 per cent of GDP on defence, the target set for all NATO member states”. Only Germany, Slovenia and Slovakia recorded lower levels of support for this statement. In 2021, the picture did not change, with only 35 per cent of Italians agreeing with the statement.

Against this backdrop, one may ask whether providing more information on the NATO target may change the results, influencing Italians to be more forthcoming on the topic.

Some initial evidence can be drawn from the 2011 Transatlantic Trends survey. Half of the sample received a statement calling for increased military spending by mentioning that “the NATO alliance urged its member states to maintain or increase defence spending in order to modernise weapons and respond to future threats”. The other half of the respondents, randomly sampled, were simply asked whether they would prefer to increase, decrease or leave military spending unchanged.

The effects of a direct reference to NATO in the question were found to be minimal and counter-intuitive: the already small percentage in favour of increasing military spending fell from 11 per cent to 9 per cent when a direct reference was made to the NATO commitment.

This dynamic has been more systematically explored in the annual survey on Italian foreign policy conducted by the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) and the Laboratorio Analisi Politiche e Sociali (LAPS) at the University of Siena.[5] In 2017, the IAI-LAPS survey addressed the issue directly, framing a question on military spending as follows: “The heads of state and government of the 28 NATO countries agreed that, by 2024, each member should allocate at least 2 per cent of GDP to military spending. Italy currently spends 1.1 per cent of GDP. Are you in favour or against increasing Italian military expenditure?”.[6]

While all respondents were provided with this input, one half of the sample was given additional information about the average defence budget (as a percentage of GDP) of other European countries and the United States.

This information had a limited effect on the results, with support for military spending increasing from 19 to 24 per cent in the sample where data was given about average European and US defence spending.

In 2018, a similar question was asked, but this time the comparison was between respondents informed of both NATO commitments and the expenditures of other Western countries and those who were not given such information.[7] In this case, the outcome was in line with that of the 2011 Transatlantic Trends survey: support for increased military expenditures dropped from 46 per cent to 35 per cent when the additional information on the 2 per cent NATO pledge and the expenditures of other countries was provided.

In the fall of 2021, the same question produced similar results, albeit these demonstrated a comparatively higher level of support for increased military spending. In this case, support for military spending dropping from 60 per cent to 47 per cent when respondents were given details about NATO commitments and the expenditures of other countries.[8] This seems to suggest a systematically negative effect of providing information on NATO commitments and the average spending of other states.

At closer scrutiny, this effect is most likely due to the specific wording of the question, especially the comparison it draws between Italian spending and that of other countries. It is the comparative element, and how this is framed, that generates important effects on the respondent. When faced with comparisons between Italy’s military expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) and that of other Western countries, Italians formulate a view that is consistent with the information they receive.

If the comparison shows that Italy spends less than the average (as happened in the 2017 survey), then a small but meaningful percentage of respondents shifts in favour of increasing expenditure. Conversely, if the comparison reports that some European countries (namely, Germany) spend about the same as Italy does, then Italians seem to conclude that they are not too far behind, and the number of those in favour of increasing military spending decreases.

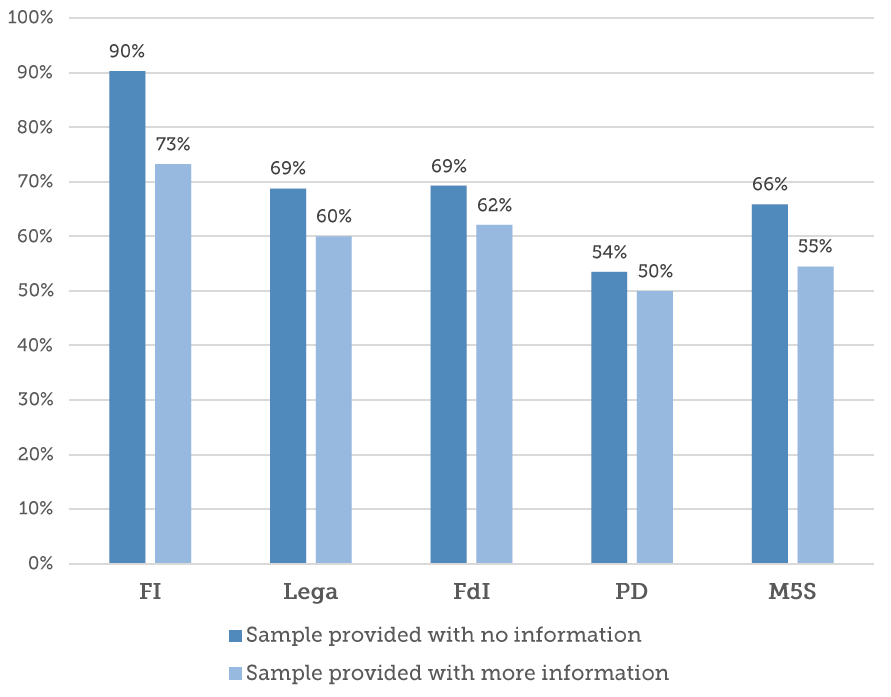

In addition to these framing effects, political and ideological cleavages need to be considered as well. Figure 1 shows the differences among voters of the main Italian political parties. While the exact figures may be affected by the limited sample size, the underlying pattern is nonetheless relevant.

Figure 1 | Support for increased military expenditure by level of information provided and party orientation (September 2021)

Source: IAI-LAPS survey, September 2021.

In line with the positions traditionally taken by Italian parties, in 2021 (and presumably at the time of writing as well), there is a solid majority in the centre-right electorate (reaching 73 per cent among Forza Italia (FI) voters, 63 per cent among the Brothers of Italy party (Fratelli d’Italia – FdI) and dropping to 60 per cent among the League’s electorate)[9] in favour of an increase in military expenditures. On the contrary, voters of the centre-left Democratic Party (Partito Democratico – PD) and the 5 Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle – M5S) are internally divided, with only half of PD voters and 55 per cent of the M5S electorate supporting an increase in military spending before the outbreak of the war in Ukraine (Figure 1).[10]

The Italian electorate is evidently split on the topic of increasing defence expenditures, with centre-right voters mostly in favour, while the centre-left is polarised. Securing the support of Italian public opinion to meet the 2 per cent GDP target will be no easy feat for the Draghi government, as witnessed by the recent political tensions within the governing coalition following the announcement of the 2 per cent increase in mid-March. Ultimately, a compromise was reached within the government, with Italy agreeing to gradually increase defence spending to 2 per cent of GDP by 2028 (as opposed to 2024 as originally claimed).[11]

Whether and to what extent the war in Ukraine has changed this picture, leading to more favourable views on the topic of Italian defence expenditures, will be the object of further assessment, beginning from the new 2022 IAI-LAPS survey expected in the fall of this year.

Pierangelo Isernia os Professor of Political Science and Jean Monnet Chair in Culture and International Relations at the Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences, University of Siena. Rossella Borri is Field manager at the Laboratory of Political and Social Analysis (LAPS), Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences, University of Siena. Sergio Martini is Post-doctoral Researcher at the Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences, University of Siena.

[1] Gianluca De Rossi, “Ukraine. ‘Italy Increases Military Spending to 2% of GDP’, Yes from the Chamber. How Much Russia and NATO Spend on Arms”, in Il Messaggero, 17 March 2022, https://www.ilmessaggero.it/en/ukraine._italy_increases_military_spending_to_2_of_gdp_yes_from_the_chamber._how_much_russia_and_nato_spend_on_arms-6569481.html.

[2] See the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, https://milex.sipri.org/sipri.

[3] Pierangelo Isernia, “Difesa: quanti italiani disposti a spendere di più e perché”, in AffarInternazionali, 9 September 2019, https://www.affarinternazionali.it/archivio-affarinternazionali/?p=75308.

[4] The survey was part of a project funded by the Volkswagen Foundation and conducted by four European universities, including that of Siena. SecEUrity project website: https://www.mzes.uni-mannheim.de/seceurity.

[5] See the list of IAI-LAPS publications: https://www.iai.it/en/node/804.

[6] IAI-LAPS, Gli italiani e la politica estera 2017, Rome, IAI, October 2017, p. 15, https://www.iai.it/en/node/8352.

[7] See IAI-LAPS, “Italians and Defence”, in Documenti IAI, No. 19|08e (April 2019), p. 15-16, https://www.iai.it/en/node/10228.

[8] IAI-LAPS, Afghanistan, missioni all’estero e spese militari: le opinioni degli italiani, Rome, IAI, September 2021, p. 9-10, https://www.iai.it/en/node/14100; IAI-LAPS, Gli italiani e la politica estera 2021, Rome, IAI, November 2021, p. 13-15, https://www.iai.it/en/node/14327.

[9] The figures refer to respondents in the sample provided with more information.

[10] The figures refer to respondents in the sample provided with more information.

[11] Niccolò Carratelli, “‘Gradualità nelle spese militari’, il M5S incassa il compromesso”, in La Stampa, 31 March 2022, https://www.lastampa.it/politica/2022/03/31/news/gradualita_nelle_spese_militari_il_m5s_incassa_il_compromesso-2913227.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, aprile 2021, 5 p. -

In:

-

Numero

22|20

Tema

Tag

Contenuti collegati

-

Ricerca06/01/2014

Indagine demoscopica sulla politica estera italiana

leggi tutto