Italians and Defence at the Time of the Ukraine War: Winds of Change

In 2022, Italians have become more concerned about tensions between Russia and the West – but not more pro-American. They rather largely trust the European Union as a security actor, or lean towards an autonomous national defence policy – quite a change for the Italian public opinion. Italians are mostly supportive of military operations abroad and do not rule out the use of force, especially when national security is directly at stake, thus confirming the post-Cold War evolution of Italy’s strategic culture.[1] Notably, in the year of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the majority in favour of defending a NATO ally under attack has risen by 9 per cent, showing an unprecedented awareness of the importance of Euro-Atlantic collective defence. These are the main novelties in Italians’ views of defence issues at a time marked by a full-fledged war in Europe and its multiple consequences for national interests, as highlighted by the 2022 edition of the periodic IAI-LAPS survey on Italy’s foreign and defence policy.[2]

The priorities: Russia, nuclear war and climate emergency

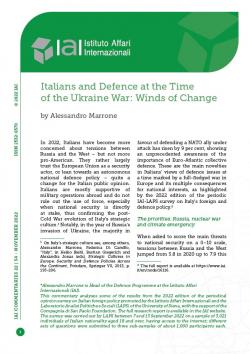

When asked to score the main threats to national security on a 0–10 scale, tensions between Russia and the West jumped from 5.8 in 2020 up to 7.9 this year. This reflects the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its unprecedented media coverage in Italy. Over the last nine months, the war has indeed been the subject of mainstream TV, radio and newspaper outlets that reach an extremely large audience but usually do not deal with international security.

in addition to tensions with Russia, the other most worrying threats include the possibility of a nuclear war – in all likelihood, a preoccupation linked to Moscow’s behaviour too – which scores 8.1, and, as the number one priority scoring 8.3, the climate emergency that still resonates strongly among the Italian public.

In parallel, China’s rise as a global power is increasingly perceived as a threat to Italy’s national security (up from 5.7 in 2018 to 6.9 in 2022). This gradual but steady trend of increasing anxiety about China’s international role is notable, given that it relates to a factor that is not immediately apparent in everyday life nor much covered by the Italian media: Beijing got public attention in relation to national security only in the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, when China first concealed for a long time the spread of the virus in Wuhan and then carried out a “mask diplomacy” propaganda campaign targeting European countries including Italy.[3]

More nationalistic, but quite pro-European too

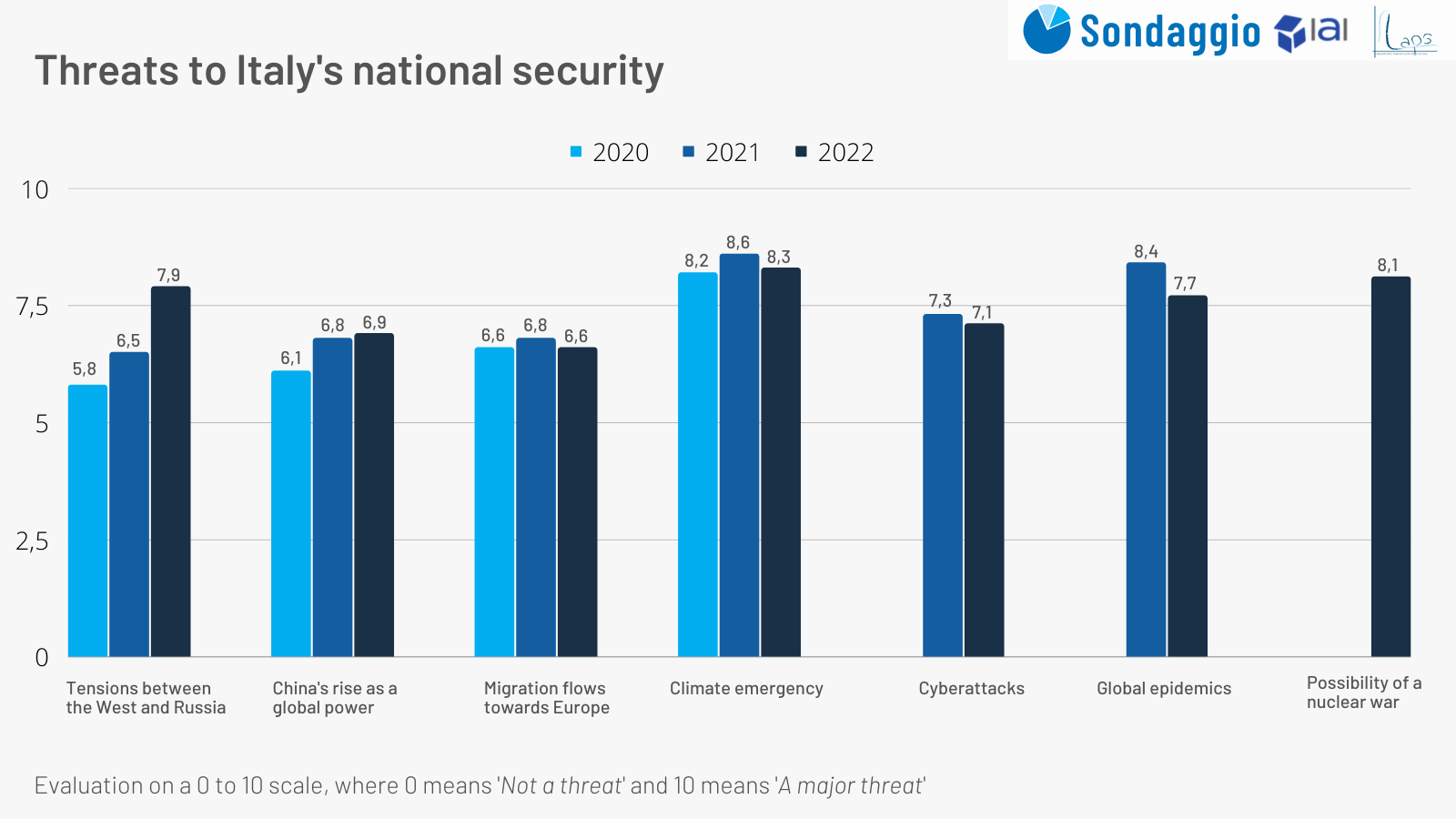

If threat perceptions evolve, preferences on the security partnerships to deal with such threats do change too. The EU is currently the “best ally” for 34 per cent of Italians, as in 2018, after a drop to 27 per cent in 2020. Such a fluctuation is probably the result of a more general improvement in Italian perceptions of the Union due to the adoption of the EU Recovery Fund. Moreover, it mirrors the significant evolution of major Italian political parties across the political spectrum from hard-core euro-scepticism to a mild form of constructive criticism of how the EU currently works. Interestingly, those who see the EU as the “best ally” for Italy stand at 30 per cent among voters of the conservative coalition led by the new Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, while they fluctuate between 39 and 50 per cent among the other coalitions.

While cooperating with both the US and the EU was the best choice for 41 per cent of Italians in 2018, it is down to only 28 per cent today. Support for a preferential partnership with Washington is even lower. It seems that growing concerns about tensions between Russia and the West do not automatically translate into a preference for a transatlantic leadership – or, at least, for the current one.[4] By totalling those favouring both the US and the EU and those giving priority to the alliance only with the Union, the latter is supported as security partner by 62 per cent of Italians. This is slightly below the latest available Eurobarometer survey, whereby 73 per cent of Italians are in favour of EU common security and defence policy.[5]

In parallel, over the last four years, the percentage of those who want a more autonomous Italian policy from both the European and the transatlantic allies has risen from 13 to 31 per cent (34 per cent among conservatives). This is in line with a broader historical trend that, after the end of the Cold War, has seen Italy gradually becoming more explicit about its own national interests and how to protect and promote them also through defence policy. The White Paper for International Security and Defence adopted in 2015 by the-then progressive government set a milestone, explicitly placing national interests at the core of Italy’s defence policy goals.[6] In addition, over the past decade, at least until the approval of the EU Recovery Fund, a series of crises relevant to Italy – the financial, the Libyan, the migratory and the pandemic ones – have seen a limited and mixed contribution from multilateral organisations, which has favoured the emergence of more nationalistic attitudes over time.

Military operations abroad: A stable support

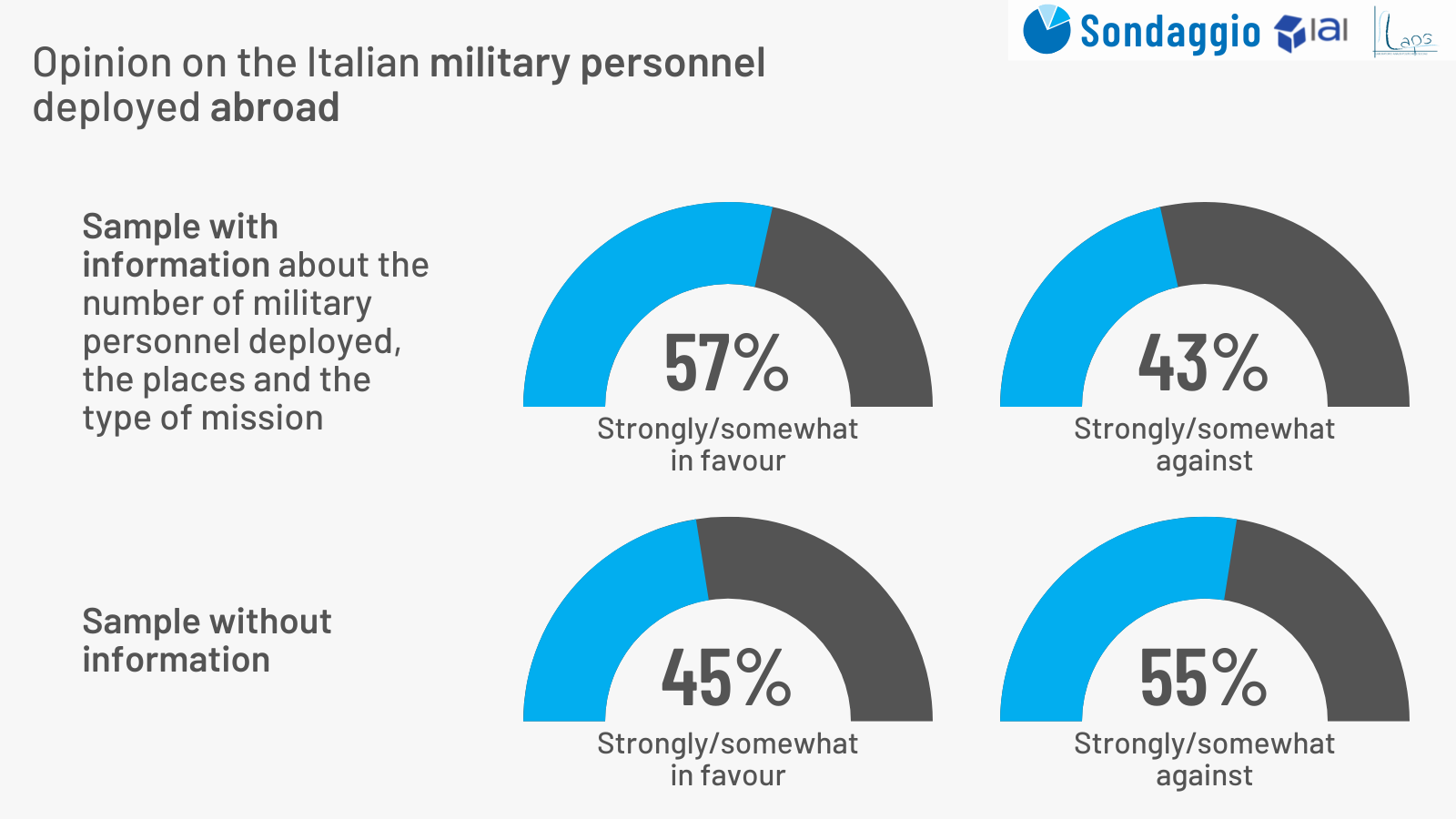

When it comes to the deployment of the Italian military, knowledge (or lack thereof) of their current crisis management and stability operations has an important effect on the views of Italian interviewees. If they are given some basic information on the number of Italian military personnel deployed abroad, the countries in which the latter are present and the missions’ framework, 57 per cent of interviewees support such engagement. On the contrary, when answering a generic question on military deployments abroad, those in favour drop by 12 points down to 45 per cent: in other words, better information brings about larger, more informed consensus. This is particularly important considering the track record of Italian military deployments under UN, EU and NATO aegis, as well as through ad-hoc coalitions, in Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia since the early 1990s.[7] As of 2022, Italy deploys about 8,500 units in 36 operations in 20 countries.[8]

Beyond ongoing operations, the percentage of Italians who would consider the use of the military ranges between 69 and 88 per cent, depending on the objective to be pursued. In principle, 74 per cent of interviewees are in favour of military intervention to end a civil war, 72 per cent to remove a government that does not respect human rights and 74 per cent in the case of peace-keeping missions. Overall, this confirms steady support for military operations abroad, including ongoing and potential ones, already highlighted by the 2019 IAI-LAPS survey: at that time, the absolute majority of Italians were still in favour of participating in deployments such as the one in Afghanistan, despite the losses and costs it had implied for almost two decades.[9]

Notably, the percentage of those in favour of the use of force is the highest – 88 per cent – in the case of Italian soldiers acting to prevent an imminent terrorist attack against Italy or to free nationals held hostage abroad. These are types of missions other than traditional peace-keeping or stability operations aimed at enforcing international law and taking place within multilateral frameworks – two long-term features of Italian military deployments since the 1980s.[10]

In a nutshell, a more immediate and nationalistic vision seems to be gradually emerging with regard to a possible use of military force, heralding somehow a wind of change. This is not to say that Italians are less keen on stability and peace-keeping operations, but these are no longer the only options that the Italian public would consider.

Greater support for NATO allies after Russia’s invasion

The type of military mission that would gather the lowest consensus (68 per cent) is the defence of a NATO ally under attack. Media coverage of the war against Ukraine – a large-scale conventional war fought in Europe – as well as the risk of Russian escalation against a NATO member probably led to more cautious and realistic answers in response to a scenario that looks both more concerning and more likely than many others.

To be sure, this is still relatively high support, well beyond two-thirds of interviewees. Moreover, and most importantly perhaps, it is higher than in 2019, when “only” 59 per cent said that they would agree to the use of the Italian military to defend a NATO ally. Such an increase in support is remarkable, considering that today this scenario is much more likely than three years ago.

The bottom line is that Italians largely aspire to a more autonomous defence policy, while maintaining robust trust in the EU as a security actor, and would also consider military operations more directly linked to national security. At the same time, the Italian public’s commitment to NATO collective defence is strengthened after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, amidst concerns about Moscow, nuclear wars, but also Beijing’s rising influence and the climate emergency.

In this context, a sound debate on national interests is obviously important for the development of Italy’s defence policy and foreign policy more generally. This should be pursued in a pragmatic and realistic way, taking into account budget constraints, adopting with a long-term perspective and a constructive approach towards the European and transatlantic frameworks as the first avenues for promoting and protecting these interests. Winds of change are blowing in a watershed year marked by a full-scale war in Europe.

Alessandro Marrone is Head of the Defence Programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

This commentary analyses some of the results from the 2022 edition of the periodical opinion survey on Italian foreign policy promoted by the Istituto Affari Internazionali and the Laboratorio Analisi Politiche e Sociali (LAPS) of the University of Siena, with the support of the Compagnia di San Paolo Foundation. The full research report is available in the IAI website. The survey was carried out by LAPS between 7 and 13 September 2022 on a sample of 3,021 individuals of Italian nationality aged 18 and over, having access to the internet; different sets of questions were submitted to three sub-samples of about 1,000 participants each.

[1] On Italy’s strategic culture see, among others, Alessandro Marrone, Federica Di Camillo, “Italy”, in Heiko Biehl, Bastian Giegerich and Alexandra Jonas (eds), Strategic Cultures in Europe. Security and Defence Policies Across the Continent, Potsdam, Springer VS, 2013, p. 193-206.

[2] The full report is available at https://www.iai.it/en/node/16116.

[3] Nathalie Tocci, “International Order and the European Project in Times of COVID19”, in IAI Commentaries, No. 20|09 (March 2020), https://www.iai.it/en/node/11408.

[4] For an analysis of post-Cold War US-Italy relations see Leopoldo Nuti, “An Overview of US-Italian Relations: The Legacy of the Past”, in IAI Papers, No. 22|02 (March 2022), https://www.iai.it/en/node/14776.

[5] European Commission Directorate-General for Communication, Standard Eurobarometer 97 - Summer 2022, 2022, https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2693.

[6] Italian Ministry of Defence, White Paper for International Security and Defence, July 2015, https://www.difesa.it/Primo_Piano/Documents/2015/07_Luglio/White%20book.pdf.

[7] For an in-depth analysis of Italian military operations abroad see Valerio Vignoli and Fabrizio Coticchia, “Italy’s Military Operations Abroad (1945–2020): Data, Patterns, and Trends”, in International Peacekeeping, Vol. 29, No. 3 (2022), p. 436-462.

[8] Italian Ministry of Defence website: Military Operations, accessed 7 November 2022, https://www.difesa.it/EN/Operations/Pagine/MilitaryOperations.aspx.

[9] Karolina Muti and Alessandro Marrone, “How Italians View Their Defence? Active, Security-oriented, Cooperative and Cheap”, in IAI Commentaries, No. 19|39 (June 2019), https://www.iai.it/en/node/10557.

[10] On the features of Italian operations and the related public debate until 2011 see Piero Ignazi, Giampiero Giacomello and Fabrizio Coticchia, Italian Military Operations Abroad. Just Don’t Call It War, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, novembre 2022, 6 p. -

In:

-

Numero

22|54