Leading the Way? Italy's External Migration Policies and the 2018 Elections: An Uncertain Future

Leading the Way? Italy’s External Migration Policies and the 2018 Elections: An Uncertain Future

Anja Palm*

Many have described 2017 as a turning point for Italy’s external migration policies. A large portion of responsibility has been ascribed to Marco Minniti, a veteran of Italy’s secret services and since December 2016 Minister of the Interior in the centre-left coalition government led by the Democratic Party (Partito Democratico, PD). But what have been the fundamentals of Italy’s migration policy and what can one expect of these policies following the Italian elections on 4 March 2018?

Italy has long called for a common EU level approach to address migratory flows. Following the 2016 EU-Turkey deal and its success in curbing arrivals along the Eastern Mediterranean Route, Italy pushed for a “replication” of this approach in North Africa. While some “successes” (i.e. the Valletta Summit, the Migration Partnership Framework and the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – EUTF) were achieved, with elections fast approaching and mounting uneasiness among the Italian public, the government deemed it necessary to take additional action.

In 2017, Italy’s approach to migration progressed along three parallel lines: the search for EU consensus and support; the strong push for the creation of a “coalition of the willing” (composed of Italy, Germany, France and recently also Spain); and the development of significant bilateral initiatives that would be supported both politically and financially by the EU. Out of these, it is the latter approach that is dubbed the most incisive. Yet, it is also the most controversial.

The Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding signed on 2 February 2017 set off a renewed, and for certain aspects unprecedented, era of Italian bilateral agreements aimed at addressing migratory flows. The resumption of collaboration on migration management with Libya, which turned Italy into the most present state-actor on the ground,[1] has been criticized due to Libya’s criminalization of migration and the widespread use of arbitrary detention as well as the complete lack of a local asylum framework. In addition to strengthening the land border control system through cooperation with local authorities and the UN-backed government in Tripoli, Italy focused on reinforcing the capabilities of the Libyan “Coast Guard”, as well as drafting a “code of conduct” for international NGOs running search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean.

While media and political debates concentrated on Libya and the Mediterranean, the government moved its focus further south, towards origin and transit countries in the Sahel, where a significant Italian presence constitutes a novelty. Niger, the prime passageway for the majority of Sub-Saharan migrants bound to Libya and then Italy, was identified as a key partner for migration management. As a result, the country has recently emerged as the main beneficiary of Italian aid, mainly through a budget support project for the development of local border management capacities. In parallel, Italy approved a military mission to Niger, with the deployment of 470 soldiers and 130 vehicles aimed at training local forces, but also to directly engage in border surveillance and control activities.[2]

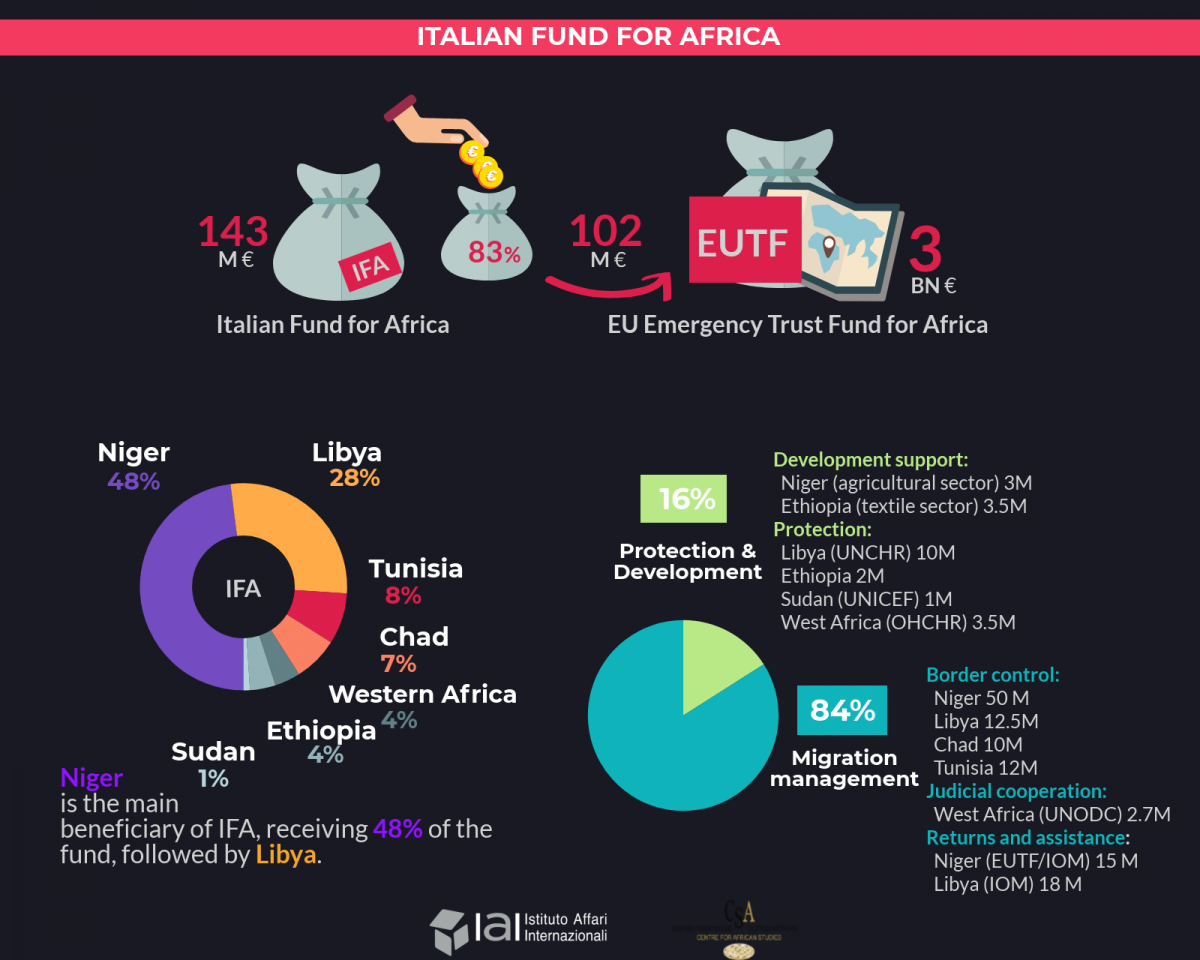

Such initiatives necessitated a significant financial effort. Italy therefore stepped up its support to EU programmes (with 102 million euro pledged and disbursed to the EUTF, Italy is the second biggest contributor after Germany),[3] and created a 200 million euro Italian Fund for Africa (IFA). The strong links between national and European actions are demonstrated by the fact that 83 per cent of Italian contributions to the EUTF originate from the IFA,[4] and that certain EUTF financed projects are being managed or implemented by the Italian Agency for Cooperation and Development (AICS) or the Italian Ministry of the Interior.

With Italy seeking to promote its “three P’s-approach” (partnerships, protection and prosperity)[5] and a long-term engagement focusing on the security-migration-development nexus in order to fight the root causes of displacement,[6] such approaches were often criticized due to a marked trend of using development funds for security related programmes aimed at border control and reducing migratory flows.[7] It was on these grounds that the Italian Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI) recently challenged the government’s handling of the IFA before a regional administrative court.[8] A look at projects implemented under the IFA confirms an overarching focus on migration management. Out of a total of 143.2 million euro so far allocated, 120.2 million were spent for such initiatives, leaving only 23 million for projects exclusively focusing on the protection of migrants and development support.[9] Similar criticism has been raised regarding the EUTF.[10]

A number of further challenges emerge from these policy choices however. The most pressing is the “bottle-neck effect”, which has seen more than 1.3 million people in need of humanitarian assistance in Libya,[11] with the numbers of migrants held in detention centres nearly triplicating between September-November 2017.[12]

In this context, some have argued that Italy may be in violation of international law, based on the financial and technical support it provides to key players in Libya that have breached international refugee and human rights obligations.[13] In order to respond to the humanitarian emergency, an Emergency Transit Mechanism by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has been established from Libya to Niger, with the aim of a controlled resettlement scheme to Europe.[14] Nevertheless, so far, EU member state engagement on resettlement and legal corridors has been slow to say the least. Some positive exceptions have materialized, such as the Italian humanitarian corridors,[15] which will hopefully fuel discussions regarding regular access channels to Europe in the future.

Notwithstanding the centre-left’s efforts over the last year, which successfully reduced arrivals to Italy by 34 per cent compared to 2016,[16] 64 per cent of respondents still consider Italian migration policies in a negative light as of early this year.[17] This has influenced public discourse and the electoral campaign, particularly as far as the other two big political fronts are concerned, namely the right-wing coalition and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S). Both have heavily criticized the PD on the migration issue.

The electoral programmes of these parties take a much harder stance on stopping migratory flows, highlighting the unrealistic objective of “zero landings”, to be obtained through the pushback of migrants and forced returns, (willingly) ignoring that Italy had already been condemned by the European Court for Human Rights for the former action back in 2012.[18]

As a result, the Italian electoral campaign has been characterized by increasingly xenophobic and anti-migratory rhetoric. Some examples include electoral manifestos of the right-wing Lega party with large slogans that include “Italians first” or “stop the invasion”. Such rhetoric is not dissimilar to that taking place in other European countries. Yet, in Italy, tensions reached a boiling point, culminating in numerous instances of physical attacks and acts of intimidation against migrants, refugees and personalities taking a more open stance on the phenomenon.[19]

Most recently, the racially motivated shooting attack carried out by an Italian citizen in the town of Macerata provides an extreme but worrying sign of the current tensions and divisions in Italian society. Yet, the reactions, ranging from condemnation to expressions of sympathy for the attacker, have also revealed the bitter undertones of the national debate, with an increasing tendency to systematically associate migration with insecurity, and some political parties throwing further fuel on the fire by promoting distorted facts and statements.[20]

In the event of a victory or a lead coalition role for the M5S or the right-wing coalition one can expect a further enhancement of restrictive measures on the migration front, potentially overstepping legal and moral boundaries. If Italy was proud about the leading role it has assumed in external migration policies over the last years, a role that won the country much praise (and criticism) across Europe, the big question today is where the new government will take these policies and how these will relate to Italy’s other foreign policy and security priorities.

One potential silver lining is that, aside from the repressive actions advanced during the campaign, we can presume that whoever takes office will be forced to trace a more moderate stance, taking a more realistic approach to the migration phenomenon.

Nevertheless, it is the general framing of the issue in increasingly racist terms that is worrying. In this sense, the elections have heralded a new era of tolerated discrimination in Italy, a dynamic that will haunt the country well beyond the 4 March vote.

* Anja Palm is Junior Researcher at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

[1] Chiara Loschi and Luca Raineri, “Perceptions about the EU’s Crisis Response in Libya”, in EUNPACK Policy Briefs, September 2017, p. 7, http://www.eunpack.eu/node/87.

[2] Italian Ministry of Defence, Increased Engagement in the Mediterranean Area, Military Presence in Iraq Halved, 15 January 2018, https://goo.gl/RacMcx.

[3] European Commission, EU Member States & Other Donors Contributions, last updated 26 February 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/trust-fund-financials_en.

[4] Interview of the author with DG Europe of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 19 October 2017.

[5] Speech by Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Angelino Alfano in occasion of the AVSI event “Refugees and Migrants. Ideas and Best Practices on Development Cooperation and the Need for Security”, New York, 19 September 2017, https://www.esteri.it/mae/en/sala_stampa/interventi/discorso-dell-on-ministro-all-evento_9.html.

[6] Joshua Massarenti, “Mario Giro: ‘La politica europea di sviluppo legata alle migrazioni’”, in Vita, 20 May 2017, http://www.vita.it/it/article/2017/05/20/mario-giro-la-politica-europea-di-sviluppo-legata-alle-migrazioni/143447.

[7] For an analysis of externalization policies see: Anja Palm, “The EU External Policy on Migration and Asylum: What Role for Italy in Shaping Its Future?”, in Observatory on European Migration Law Policy Briefs, May 2017, http://migration.jus.unipi.it/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2017/05/Policy-Brief-External-Dimension.pdf.

[8] European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), NGO Takes Italy to Court over Misappropriation of Development Funds Directed to Libyan Coastguards, 24 November 2017, https://www.ecre.org/?p=5184.

[9] Andrea Stocchiero, “Quale futuro per il Fondo italiano per l’Africa?”, in FOCSIV Policy Briefs, No. 1/2017 (November 2017), p. 7, https://www.focsiv.it/?p=521651.

[10] Olivia De Guerry and Andrea Stocchiero, Partnership or Conditionality? Monitoring the Migration Compacts and EU Trust Fund for Africa, Brussels, Concord Europe, January 2018, https://wp.me/p76mJt-2u9; Global Health Advocates, Misplaced Trust: Diverting EU Aid to Stop Migration. The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, September 2017, http://www.ghadvocates.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Misplaced-Trust_FINAL-VERSION.pdf.

[11] UNICEF, Libya 2017 Humanitarian Situation Report, 22 January 2018, https://www.unicef.org/appeals/libya_sitreps.html.

[12] UNHCR, Suffering of Migrants in Libya Outrage to Conscience of Humanity, 14 November 2017, https://shar.es/1Lopqn. Additionally to detention centres monitored by the Libya’s Department of Combatting Illegal Migration (DCIM) to which these numbers refer, there are numerous detention facilities run by local militias.

[13] Anja Palm, “The Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding: The Baseline of a Policy Approach Aimed at Closing All Doors to Europe?”, in EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy Blog, 2 October 2017, http://eumigrationlawblog.eu/?p=1605. For further examples see: Paolo Biondi, “The Case for Italy’s Complicity in Libya Push-Backs”, in Refugees Deeply, 24 November 2017, https://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees/community/2017/11/24/the-case-for-italys-complicity-in-libya-push-backs.

[14] So far, 1,211 have been evacuated from Libya: 897 to Niger, 312 to Italy and two to Romania. UNHCR, UNHCR Libya Flash Update, 17-23 February 2018, 22 February 2018, http://reporting.unhcr.org/node/12987.

[15] So far, more than 1,000 vulnerable individuals have arrived from Lebanon since 2016. The protocol will be repeated in 2018, with another 1,000 places pledged. Another 500 will be transferred from Ethiopia (with 139 having already arrived), bringing the total number to 2,500 by the end of 2018.

[16] UNHCR, Refugee and Migrant Arrivals to Europe in 2017, 16 February 2018, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/62023.

[17] Tecnè data as reported by Carmine Saviano, “Ultimi sondaggi: gli effetti del raid di Macerata sulle intenzioni di voto”, in Repubblica, 10 February 2018, http://www.repubblica.it/politica/2018/02/10/news/ultimi_sondaggi_gli_effetti_del_raid_di_macerata_sulle_intenzioni_di_voto-188527606.

[18] European Court of Human Rights, Judgment of the Grand Chamber on the Case of Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy (Application No. 27765/09), 23 February 2012, http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-109231.

[19] See for instance, Angela Giuffrida, “Italy Used to Be a Tolerant Country, But Now Racisim Is Rising”, in The Guardian, 18 February 2018, https://gu.com/p/857vk. See also Francesca Capano, “Italy’s Draft Law on Radicalization: A Missed Opportunity?”, in IAI Commentaries, No. 17|34 (December 2017), http://www.iai.it/en/node/8652.

[20] In this sense see the website of the Italian section of Amnesty International: Il barometro dell’odio, https://www.amnesty.it/barometro-odio.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, febbraio 2018, 5 p. -

In:

-

Numero

18|12