South Africa’s G20 Presidency: Tapping into Africa’s Potential through Financial, Climate and Food System Reform

Both the G20 and BRICS+[1] are critical global groupings for economic and geostrategic reasons. Thirty years ago, G7 countries constituted nearly 70 per cent of the global economy. In contrast, by 2024, the BRICS+ bloc accounted for approximately 35 per cent of the world’s GDP, compared to the 30 per cent held by G7 countries.[2] Meanwhile, G20 countries represent 85 per cent of the global economy, 75 per cent of global trade, and 62 per cent of the world’s population.[3] This shift underscores the growing influence and significance of emerging economies.

South Africa’s membership in the G20 and BRICS+ attests to the country’s role as an economic and political powerhouse – both on the African continent and increasingly in the global South. In 2025, South Africa will assume the presidency of the G20 – the first African country to do so, taking over from Brazil. At a moment of heightened geopolitical tensions and a fragmented international system characterised by multiple and simultaneous crises, including the climate and energy crisis, and the Russian-Ukraine and Israel-Palestine wars, can South Africa’s G20 presidency be an opportunity to reshape global governance? Founded in 1999 in response to the global financial crisis, the G20 is the main forum for international cooperation and plays an important role in defining and strengthening global architecture and governance. South Africa’s presidency should consolidate priority issues established by the Brazilian government but anchor on three critical issues: reform of the global financial architecture, climate change and a just energy transition and sustainable food systems. A policy focus on these issues will lay a foundation for the continent’s leapfrogging.

Why global financial reform is more urgent than ever

With many developing countries burdened by growing debt, the need to reform the global financial architecture has never been more urgent.[4] Over 3.3 billion people live in countries that spend more on debt servicing than health, education and social protection.[5] According to the UN Trade and Development Agency, African countries’ debt has increased by 183 per cent since 2010 – four times higher than its economic growth rate over the same period.[6] As global borrowing shifts towards private creditors, many developing countries are finding it increasingly difficult to finance critical sectors that contribute to socio-economic development.

The reasons can be varied and context specific but three stand out: first, complexity of creditor base makes debt relief and restructuring extremely challenging as it requires negotiating with a wider range of creditors, sometimes with diverging interests and legal frameworks. Delays and uncertainties in debt restructuring increase the cost of resolving debt crises.

Second, lending by private creditors is volatile and prone to rapid shifts especially during crises, as investors pull back to safety. This can lead to resource outflows when poor countries least afford them. For example, in 2020, developing countries paid 49 billion US dollars more to their external creditors than they received in disbursements, resulting in a negative net resource transfer.[7]

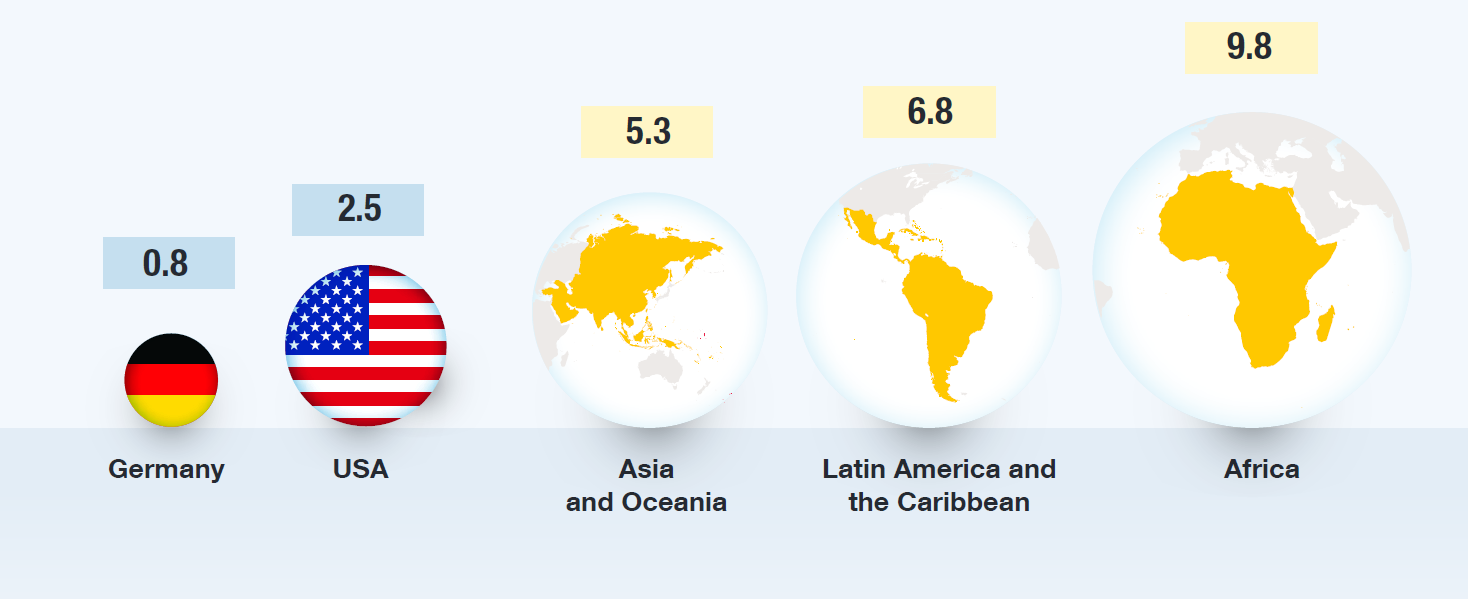

Third, borrowing from private sources on commercial terms is more expensive than concessional financing from multilateral and bilateral sources. The inequalities embedded in the international financial architecture exacerbate differences in the cost of financing. For instance, borrowing costs for developing countries range between 2-12 times higher than those of developed countries (Figure 1), making it difficult for developing countries to access and finance development. In 2023, 54 countries allocated 10 per cent or more of government revenue to interest payments.[8]

Figure 1 | Borrowing costs of developing countries are higher than those of developed ones (bond yield ratio)

Source: UNCTAD, A World of Debt, cit., p. 14.

As can be observed, the current global financial architecture is not only dysfunctional but unfit for purpose in a world characterised by complex, multilayered and interconnected crises. As a major global South actor, South Africa can leverage its membership in the African Union, G20, BRICS+ and other fora like G7 to rally support for global financial reform and advance concrete policy proposals for a responsive and inclusive global financial architecture fit for the 21st century.

More specifically, South Africa’s presidency is an opportunity to strengthen the voice and participation of developing countries in international economic decision-making, norm-setting and global economic governance. South Africa’s presidency of the G20 will coincide with the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development set for mid-2025 in Spain bringing together Heads of State and Government, the G20 group, members of the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), the Secretary General of the UN, and heads of international financial institutions. This can be an opportunity to advance policy proposals to achieve progress in building a stronger and fairer international financial system.

Climate change and a just renewable transition

While the urgency of addressing climate change and advancing a just energy transition is crucial, for Africa and the broader developing world, the priority must be ensuring energy access for the 685 million people who still lack electricity.[9] Providing affordable, clean and reliable energy is not only essential for climate mitigation and adaptation but also presents a critical opportunity to catalyse investments in the green economy. As South Africa assumes the G20 presidency and continues to be a leading voice for the Africa Group within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), it is imperative that it champions this perspective. Additionally, South Africa can play a pivotal role in translating Africa’s increased representation at COP meetings into tangible outcomes, using existing frameworks to hold the Global North accountable to its commitments to the Global South.

Rallying global consensus on climate change and a just energy transition hinges on two critical issues. First, the shift towards renewable energy must be both sustainable and equitable, ensuring that all countries, especially those in the Global South, benefit from cleaner technologies. Second, comprehensive climate change adaptation strategies must be developed and implemented, with robust finance and security packages that empower vulnerable communities to mitigate and adapt to the climate impact. By championing these priorities, South Africa can galvanise global support for a fair and inclusive response to the climate crisis, ensuring that communities are sufficiently empowered to pursue a sustainable future.

Transforming Africa’s food systems

Despite the current global food system’s capacity to produce enough food for everyone, over 900 million people experience hunger daily, and more than 2.4 billion are food insecure.[10] In Africa, this situation is exacerbated by natural disasters, wars, fragile global supply chains, and economic inequality, which underscore the vulnerabilities of a globalised food system. These interconnected challenges mean that shocks in one part of the world can rapidly spread, often with devastating effects on lives and livelihoods. The UN Food Systems Summit in 2021 aimed to address three interrelated global challenges within food systems: an increase in undernutrition and overnutrition, the unsustainable food production methods contributing to climate change and environmental degradation, and social inequities within food systems.[11] Unsustainable food production systems are central to global vulnerability to climate change and growing food insecurity. For instance, food production accounts for 26 per cent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, half of the world’s habitable land and 70 per cent of global freshwater withdrawals.[12] The Food and Land Use Coalition estimates costs related to unsustainable food systems at around 12 trillion US dollars – nearly four times more than the market value of the food system itself estimated to be 3.6 trillion US dollars in 2021.[13] Although poorer developing countries are demonstrating leadership and, in many cases, a level of ambition lacking in richer countries, they are constrained by adverse economic environments marked by slower growth, reduced revenue, rising debt service obligations and food price inflation. Against this backdrop, South Africa can drive comprehensive debt relief and restructuring mechanisms, mobilise additional financial resources and advocate for fairer global trade practices to empower developing countries.

Looking ahead

Placing these three interconnected issues at the centre of its presidency will provide space for innovative policy making to tackle the above challenges. By reforming the global financial architecture, developing countries can access finance that is key to unlocking energy access and renewable energy – itself a source of climate mitigation and adaptation. Addressing the interconnected challenges of climate and finance can help unleash Africa’s agriculture and food systems potential, thereby contributing to the continent’s leapfrogging. With Africa’s population expected to double by 2050, ensuring that people have access to affordable, reliable, and clean energy, as well as to healthy and nutritious food delivered in affordable and sustainable ways, is key to accelerating progress towards sustainable development goals and Agenda 2063.[14] Evidence including from the European Union’s Farm-to-Fork strategy shows that well-designed and properly financed agriculture programmes can help correct underlying food system failures by linking eradication of hunger to wider public health, environmental, energy and climate goals. For Africa and the developing world, such integrated approaches are crucial to address the multifaceted challenges of food insecurity, sustainable development and climate action.

Darlington Tshuma is a Researcher in the Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa Programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI). Bongiwe Mphahlele is a Post-doctoral Researcher at the Thabo Mbeki African School of Public and International Affairs, South Africa.

[1] BRICS+ is an intergovernmental organisation whose founding members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. At a BRICS summit in Johannesburg in August 2023, BRICS admitted four new members: Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates. The four new members formally joined the bloc in January 2024.

[2] Statista, BRICS and G7 Countries’ Share of the World’s Total Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) from 2000 to 2024, 15 July 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1412425.

[3] UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA) Population Division, World Population Prospects 2024 - Special Aggregates, 2024, https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/SpecialAggregates/EconomicTrading.

[4] United Nations, “Reforms to the International Financial Architecture”, in Our Common Agenda Policy Briefs, No. 6 (May 2023), https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brief-international-finance-architecture-en.pdf.

[5] United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), A World of Debt. A Growing Burden to Global Prosperity, New York, UNCTAD, 2024, p. 18, https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt.

[6] UNCTAD, A World of Debt: Regional Stories. Africa (2023), 2024, https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt/regional-stories.

[7] UNCTAD, A World of Debt, cit., p. 12.

[8] Ibid., p. 16.

[9] International Energy Agency (IEA) et al., Tracking SDG7. The Energy Progress Report, 2024, June 2024, p. 31 and 44, https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-sdg7-the-energy-progress-report-2024.

[10] UN website: Food, https://www.un.org/en/node/118143.

[11] Jennifer Clapp, Indra Noyes and Zachary Grant, “The Food Systems Summit’s Failure to Address Corporate Power”, in Development, Vol. 64, p. 192-198 at p. 192, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-021-00303-2.

[12] Benjamin S. Halpern et al., “The Environmental Footprint of Global Food Production”, in Nature Sustainability, Vol. 5, No. 12 (December 2022), p. 1027-1039, DOI 10.1038/s41893-022-00965-x.

[13] Food and Land Use Coalition, Growing Better: Ten Critical Transitions to Transform Food and Land Use, September 2019, p. 24, https://www.foodandlandusecoalition.org/?p=125.

[14] Agenda 2063 is Africa’s continental development blueprint. See African Union, Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, September 2015, https://au.int/en/node/3657.

-

Dati bibliografici

Roma, IAI, settembre 2024, 5 p. -

In:

-

Numero

24|54